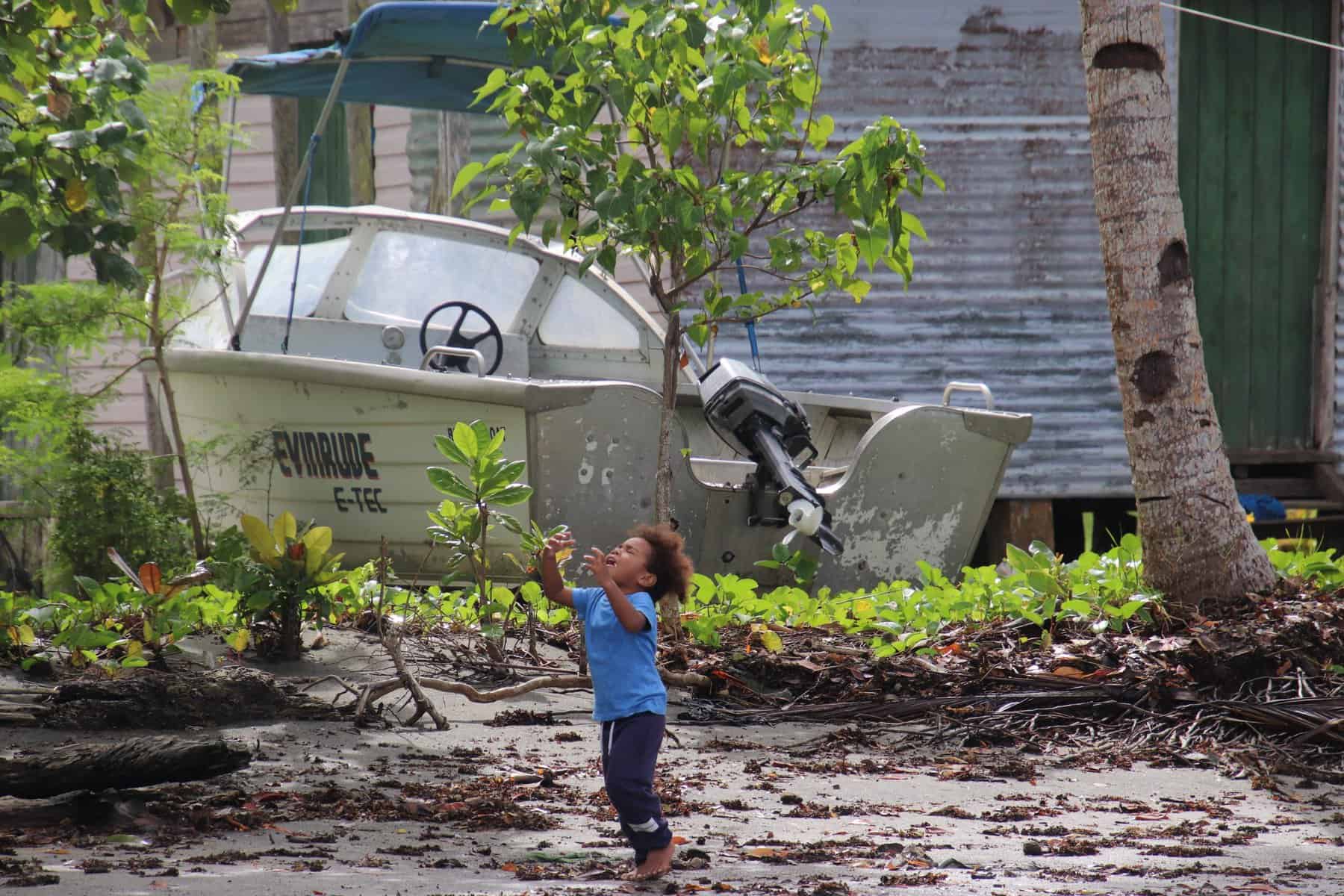

On the black sand a child ran, face turned upwards as he chased a butterfly.

Oblivious to the encroachment of rising sea levels and the gradual erosion of his village, he ran back and forth - lost in this moment.

Fifty paces away on the edge of what was once a green playing field, the people of Vunisavisavi turned their faces upwards as - with representatives of Fiji’s three oldest churches - they chased answers.

Who will stop the waves? Where can we go? Is this the end?

Rising sea levels and salt . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...