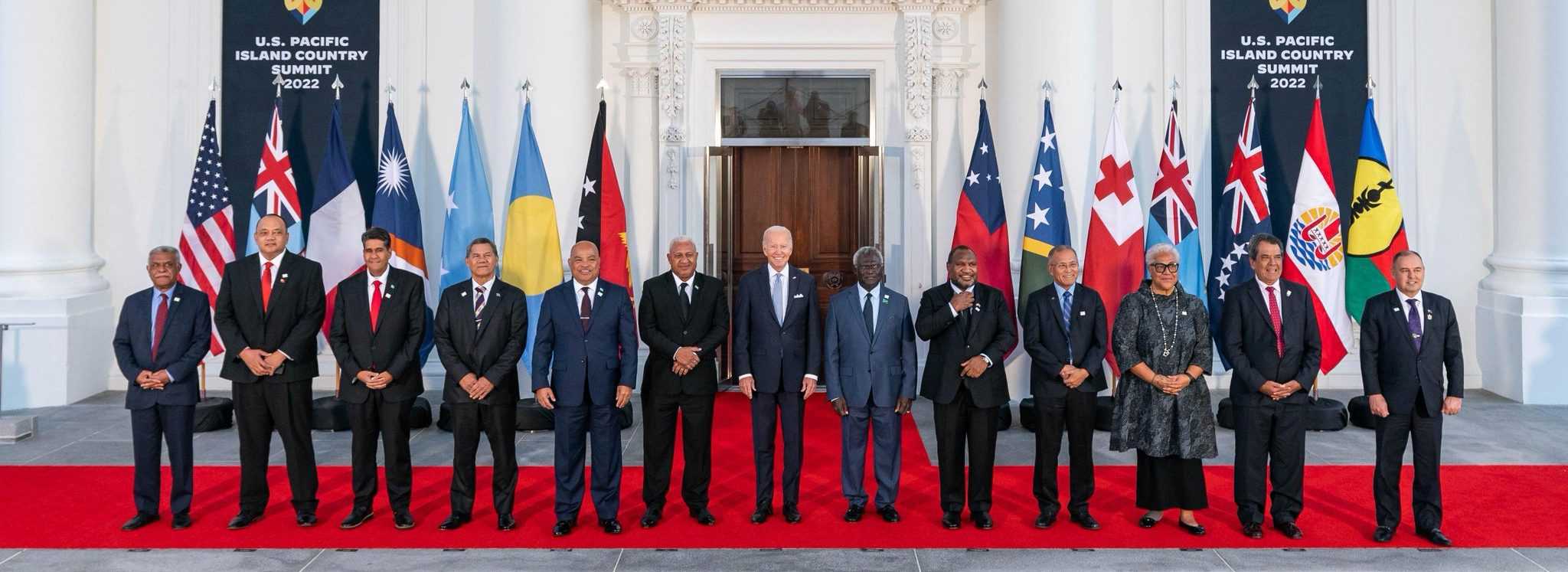

Spooked by China’s influence in the Pacific Islands, U.S. President Joe Biden hosted an unprecedented summit at the White House for leaders from the Pacific Islands Forum on 28-29 September. It was the culmination of a series of initiatives over recent months, as the U.S. government plays catch up in a complex and crowded geopolitical arena.

Overall, Pacific leaders left Washington well pleased, with an 11-point declaration of U.S.-Pacific partnership, a strong focus on climate action, a grab bag of funding pledges and significant diplomatic commitments for Forum members not . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...