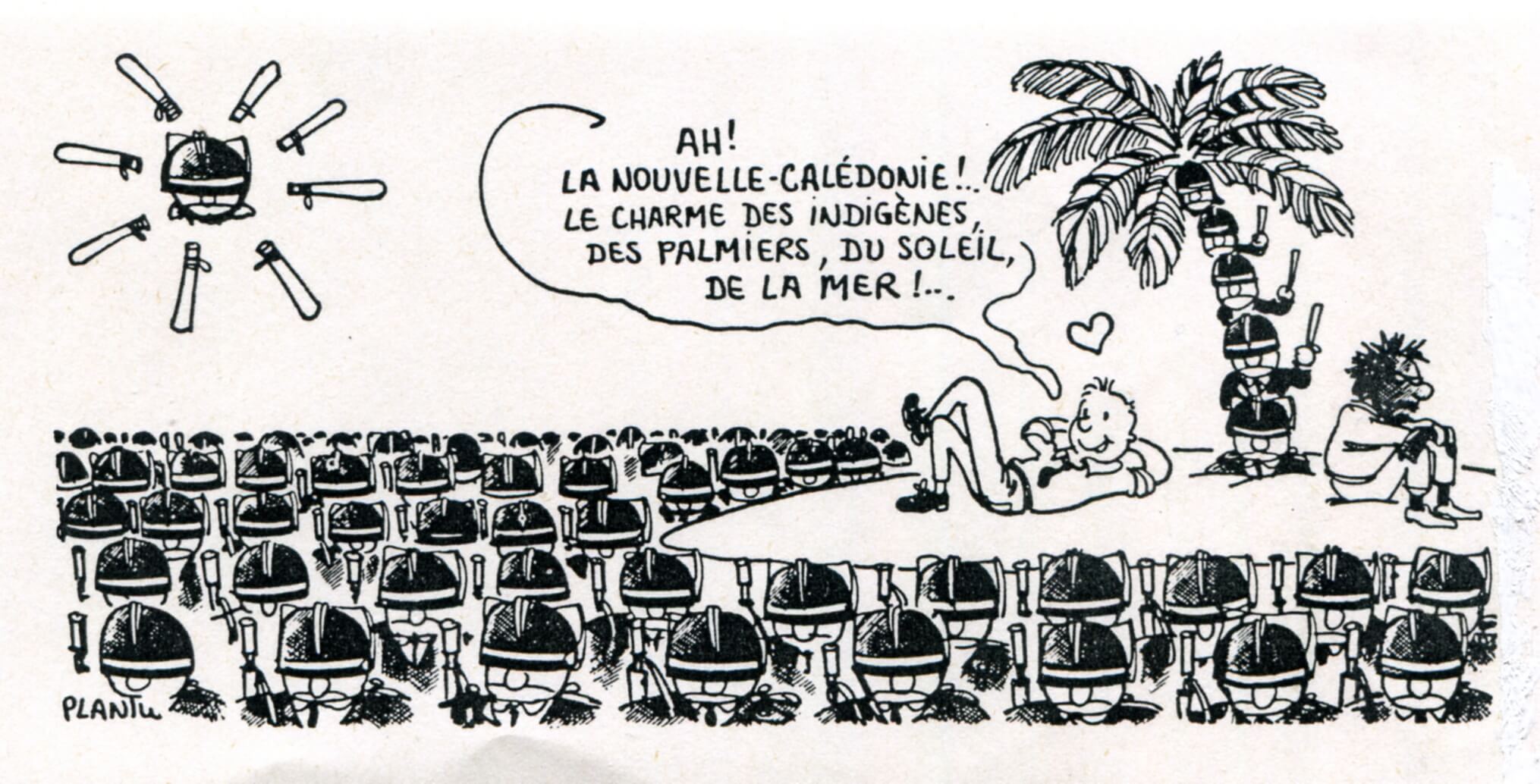

France boosts police and military before New Caledonia vote

By Nic Maclellan

As New Caledonia moves towards a referendum on self-determination on 12 December, France is deploying new police and military forces to the French Pacific dependency. In a show of strength, nearly 2,500 extra security forces – backed by armoured cars, helicopters and other equipment – will spread out across New Caledonia in the next few weeks.

All independence parties had called for the referendum to be postponed until 2022, because of disruption to campaigning during a surge of COVID . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...

One Comment “WHO: Pacific islands facing a bumpy road toward the ‘Healthy Islands’ vision”

Comments are closed.