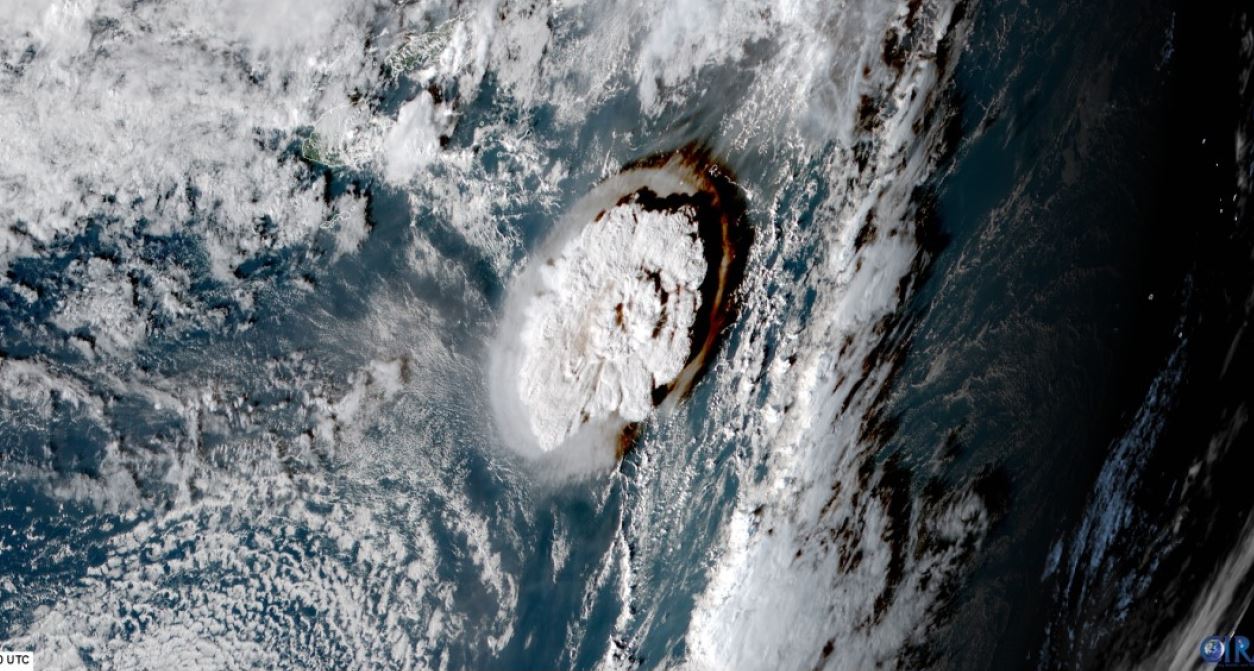

The Tonga eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in the South Pacific Ocean on 15 January, 2022 created a rare event never before detected with modern instruments. A powerful tsunami raced forward, leaving an untold number of lives hanging in the balance.

Notably, only five percent of tsunamis are triggered by volcanic activity — and this one was massive. The waves were measured thousands of miles away, as far as the Caribbean.

Immediately, NOAA scientists at the tsunami warning centers sprang to action. NOAA’s global network of ocean buoys, water-level stations and other observation tools informed tsunami alerts for coastal locations throughout the Pacific Basin, parts of Alaska and the U.S. West Coast.

NOAA communicated with emergency managers about the tsunami and potentially deadly hazards it could bring to coastlines around the Pacific. Timing and impact information was critical to making a multitude of life-safety decisions.

Historically significant

Scientists believe the last time a volcano set off a tsunami this large was the Krakatoa eruption of 1883. They can’t be sure, though, because the technology to observe ocean waters in real-time around the globe did not exist, including tsunami warnings. The Tonga eruption was the first event of its kind that scientists could track in detail as it unfolded.

“I was living through something never before experienced in this way,” said Greg Dusek, senior scientist at the NOAA National Ocean Service’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services. “Throw in that this all happened during high tide in some places, and we saw a significant event, particularly in Hawaii and California. I saw records breaking at four of our water level stations, some that have stood in place since the 1950s.”

Water levels at Kahului Harbor, Hawaii, and three locations in California (Arena Cove, Monterey and Port San Luis) reported record levels. The tsunami also hit locations as far as Alaska and the Caribbean.

An eruption unlike any other. But why?

Evidence suggests the eruption created an air pressure change above water, resulting in something similar to a meteotsunami, where an ocean wave and an atmospheric wave travel at similar speeds, building energy together as they race toward land. This sent waves all the way to the shores of the U.S East Coast. Moreover, rapid air pressure changes were recorded around the globe.

“That surprised me,” Dusek recalled. “To see changes in water levels at such broad spatial scales is another layer that scientists are studying.”

Researchers at the NOAA Centre for Tsunami Research are studying data collected from the Tonga eruption with the hope of advancing NOAA’s tsunami forecast model to account for both seismic-triggered tsunamis, the most common type, as well as those resulting from volcanic activity and air pressure changes.

“NOAA is at the early stages of research to better detect and predict large waves and how they might interact to influence coastal water levels and impact coastlines,” said Dusek.

One Comment “Ripple effect: What the Tonga eruption could mean for tsunami research”

Comments are closed.