According to recent reports, a Russian spy ship was part of a sabotage operation targeting underwater cables, gas pipelines and wind farms in the North Sea. The vessel was spotted entering Belgian and Dutch territorial waters in recent months before being detected and escorted by the Dutch coastguard and the navy.

Last October, subsea cables were cut to the Shetland Islands in Scotland, home to RAF Remote Radar Head Saxa Vord, which monitors Russian military activity in the North Sea. It’s not clear what caused the damage. In the same month in the south of France three key subsea cables connecting Marseille to Lyon, Milan, and Barcelona were purposely cut, the cable’s operator reported. Last year’s mysterious bombing of the Nord Stream gas pipeline highlighted the vulnerability of underwater infrastructure to sabotage. There’s been a suspiciously high volume of breakages in the cables connecting Taiwan with the Matsu Islands.

Closer to home, last May the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, wrote to his fellow Pacific Island leaders about the regional risks of the China–Solomon Islands security agreement. He pointed out that the “bulk of Chinese research activity in FSM has followed our nation’s fibre optic cable infrastructure”.

In recent years the US has denied permission for several subsea telecoms cables that involved Chinese companies or directly connected the US to mainland China or Hong Kong. China’s data security law mandates that domestic companies and institutions share data with the government if the information in question pertains to matters of national security. Data operated by Chinese companies is vulnerable to state interception.

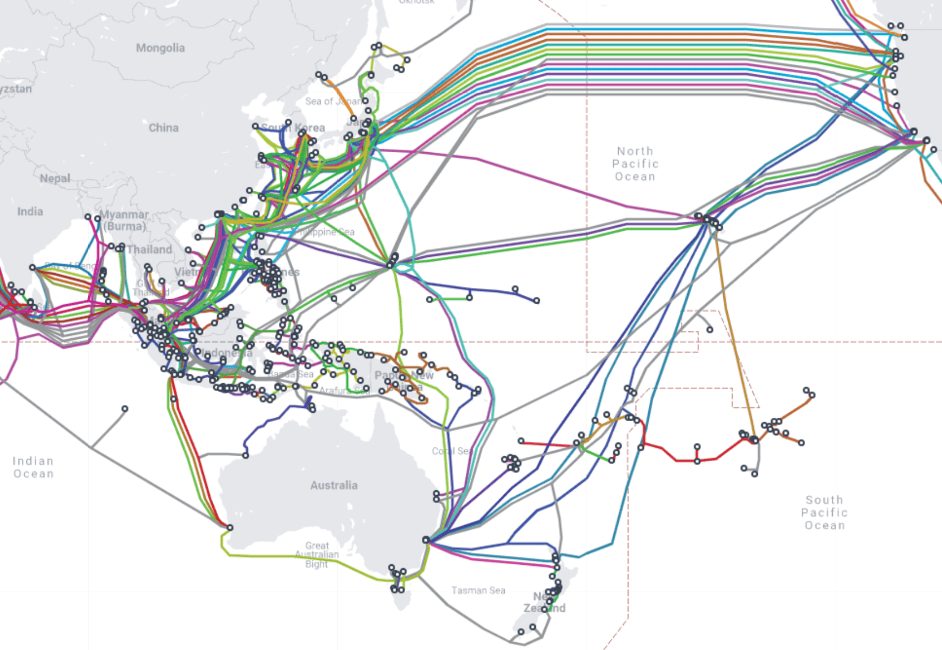

A comprehensive approach is required to address the resilience of undersea communications cables. There’s more than 430 subsea cables that may be targets for anyone wishing to disrupt global connectivity. These cables transfer more than 95 percent of international communications and data globally.

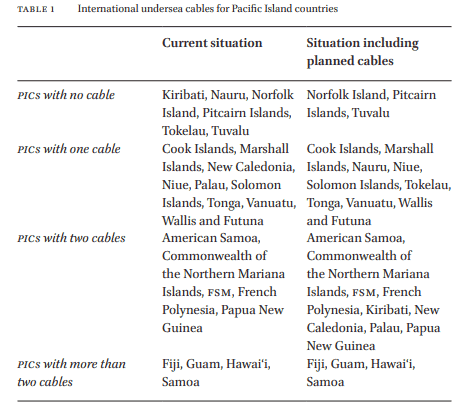

All it takes to damage a cable is a merchant ship or fishing boat dropping its anchor on a cable not far from the coast. Last year, an underwater volcano shattered Tonga’s internet infrastructure—a single cable connecting the archipelago to the global internet. It took five weeks to fix. Many Pacific Island countries rely on one system and don’t have a backup in place.

Fishing and anchoring incidents account for approximately 70percent of cable faults globally. But divers, submersibles or military grade drones could place explosives on cables or install mines nearby, which could then be detonated remotely. Cable repair ships could be attacked.

Several nations in the Indo-Pacific operate submarines capable of stealthily tampering with cables. Cable-laying companies can potentially insert backdoors or install surveillance equipment. By hacking into network-management systems, attackers could control multiple cable-management systems. Terrorists and criminal organisations could exploit cable vulnerabilities for different purposes.

A bigger threat is cable interference at data points or landing stations. Sydney and Perth are the primary points where cables land in Australia. Power could be cut to those sites or explosive devices detonated. Missile attacks are possible. Landing station locations are vulnerable: data can be intercepted and copied while the sender and receiver are none the wiser.

A draft of a maritime agreement between China and Solomon Islands that leaked last year says China’s aim is to develop “a maritime community with a shared future” by building wharves, shipyards and submarine cables for Solomon Islands. When it comes to the island states, we and our partners should continue to fund cable projects to fend off Chinese-backed alternatives.

At a national level, Australia’s submarine cable protection regime is considered a regional gold standard with protection zones around cable routes and criminalising cable interference. While each country’s geographic circumstances are different, promoting the adoption of similar legislation by our island neighbours would help safeguard their vulnerable cables.

We should work with our Pacific partners to strengthen limited regional cable-repair capabilities and cooperate with Pacific Island agencies to integrate cable surveillance into national and regional maritime domain awareness systems.

China has just appointed its first special envoy on Pacific Island affairs, the former Chinese ambassador to Fiji, Qian Bo. China’s cable industry will grow and so the battle to lay, operate and repair the critical infrastructure underpinning the global internet will intensify. And it won’t just be undersea communications cables and infrastructure that will require protection. As we push ahead on clean energy, we’ll see more undersea transnational electricity cable connections to solar farms and offshore wind farms.

Subsea cables transit the ocean seabed largely out of sight and out of mind. But it’s time to raise our preparedness and response mechanisms to improve the resilience of this critical subsea infrastructure.

Dr Anthony Bergin is a senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and expert associate at the National Security College.