Like empires past, Xi Jinping’s China seeks three grand prizes in the Pacific: wealth, control and presence. Australia and other Pacific nations have recognised the nature and scope of this neocolonial ambition and the risk it brings; responses have veered from complacency to overreaction, fatalism to alarm.

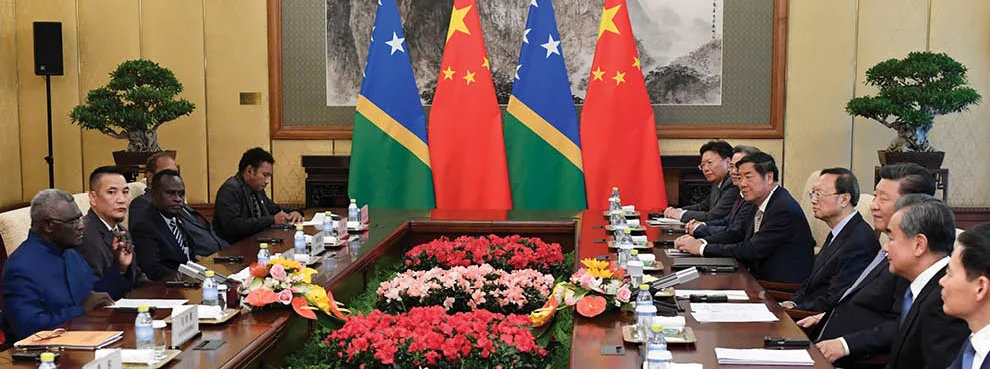

The events of 2022 – especially the controversy over China’s security agreement with Solomon Islands – have thus been a useful wake-up call. Australian interests would be directly jeopardised if China were to establish a military base so close to Australian shores. But even without that scenario, the . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...