Across Australia this month, voters will decide whether to change the Constitution and create a Voice to Parliament – a body to advise the Australian government on laws and policies that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Voters go to the polls on 14 October, to vote Yes or No on a proposed law “to alter the Constitution to recognise the first peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice”.

Elected in May 2022, the ALP government led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese pledged to hold this referendum within its first term of office. But the Voice proposal is part of a larger process on indigenous rights, addressing calls from peoples who make up just 3% of the Australian population.

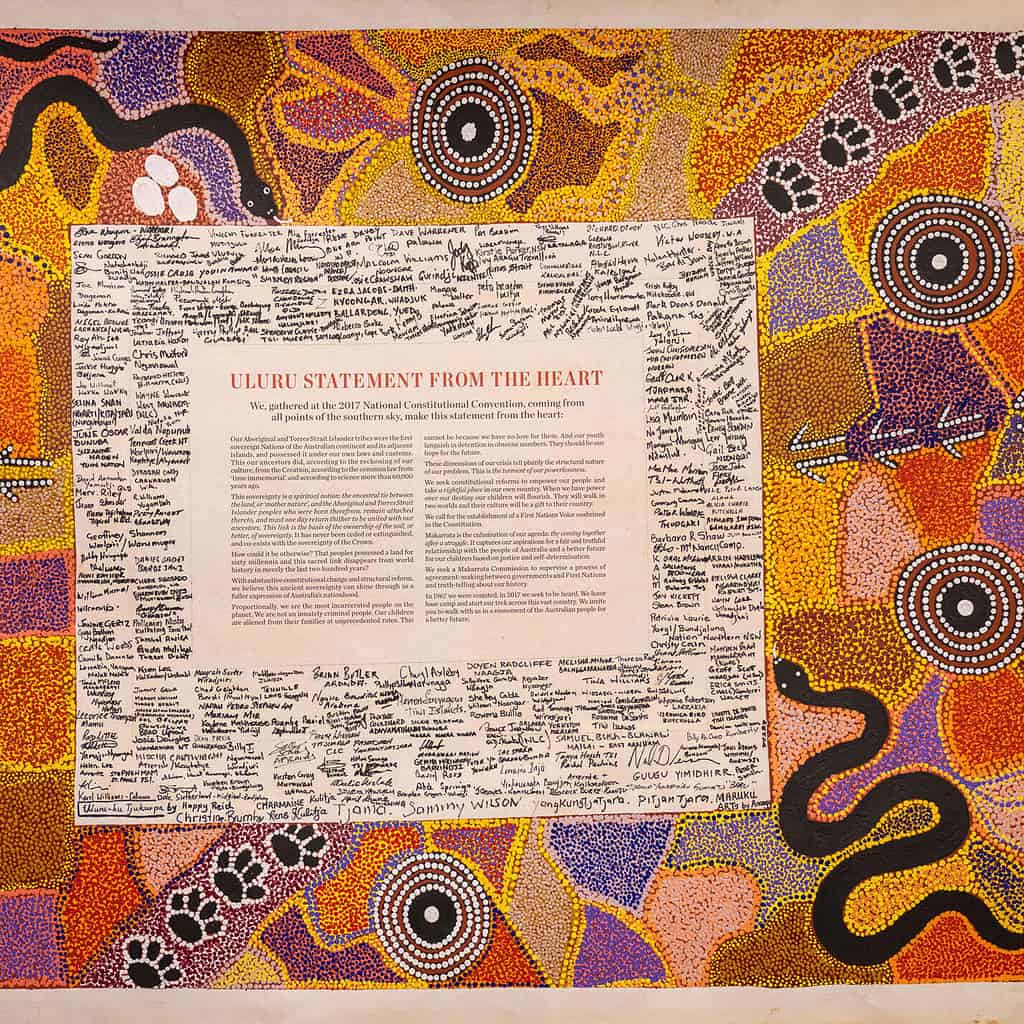

In 2017, more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders met at Uluru in the heart of central Australia. Their summit debated possible changes to the Australian constitution to formally recognise the country’s First Nations, and an overwhelming majority of participants adopted the “Uluru Statement from the Heart.”

Professor Megan Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman and a leading architect of the Uluru Statement, says indigenous peoples want Voice, Treaty and Truth: “We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution and seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreements between governments and First Nations, and truth-telling about our history.”

If adopted by this month’s referendum, the proposed Voice would be established by Parliament as an independent body, elected by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters. It would likely have local and national structures that will be able to advise parliament and government about matters affecting the lives of indigenous peoples.

In the past, there were a series of structures that served as a national forum for indigenous leaders to engage with Australian politicians and bureaucrats. But all have been subject to political pressure or de-funding: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), founded in 1990, was abolished in 2005 by the conservative Howard government. Since then, indigenous leaders have sought to entrench an advisory body within the Constitution, to protect a mechanism for ongoing representation and recognition.

Beyond this, Australia has never negotiated a formal treaty with First Nations, in contrast to other Anglophone governments that have developed treaties with sovereign indigenous peoples, such as the Treaty of Waitangi in Aotearoa (Despite this failure at national level, Northern Territory, Victoria and South Australia have all begun Treaty processes at state and territory level, including the creation of a First Nations Peoples’ Assembly in Victoria in 2019).

The third Uluru call – for Truth – involves acknowledgement, apology and potentially reparations for the sordid history that has devastated indigenous peoples and South Sea Islanders over many generations: the foundational violence of dispossession, land theft and massacres; black birding and the colonial labour trade; the White Australia policy and post-Federation deportation of Kanakas; the Stolen Generations; the systemic violence of unprecedented rates of incarceration and deaths in custody; the vast gulf between health, education and welfare levels for indigenous and non-indigenous Australians; the list goes on and on.

To counter this, the Uluru Statement celebrates a proud history of resistance and survival. It has inspired a growing awareness – especially amongst many younger Australians – of the more than 60,000 years of history and cultural heritage across the continent.

Debate and division

The campaign for a Voice, however, is in trouble. Early support for the Yes campaign has fallen away during this year. A month out from the 14 October vote, all public opinion polls show a majority of voters will reject the proposed structure.

Widespread public uncertainty about the long-term implications of the advisory body has benefited the No campaign, which has actively promoted disinformation about the legal and political effects of constitutional change. It is also notoriously hard to amend Australia’s Constitution, requiring a national majority of all Australian voters to vote Yes, but also a majority in four of the six states.

On current polling, the traditional frontier states of Queensland and Western Australia, with large indigenous populations and major mining and pastoral interests, are voting No. The larger states Victoria and New South Wales have a significant proportion of Yes voters, while South Australia and Tasmania remain crucial battlegrounds. With just weeks to go, Yes campaigners are desperately reaching out to undecided voters, fearing a historic defeat.

From the beginning, the referendum process has been fraught with resistance from conservative interests.

The National Party, representing agribusiness and many rural and regional voters, called for a No vote even before Parliament had formally debated the issue. Under opposition leader Peter Dutton, the Liberal Party has also called for a No vote (Dutton infamously walked out of Parliament for the 2008 Apology to the Stolen Generations, and has been widely criticised for fear mongering and disinformation during the latest Voice debate).

A minority of individual Liberals are calling for a Yes vote, including the first indigenous Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt. However Country Liberal Party senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, a Walpiri woman from the Northern Territory, is the lead spokesperson for the No campaign. Amplified by the Murdoch press and right-wing think tanks, Price has been the public face of indigenous opposition, calling the Voice “divisive and dangerous”, and saying it will divert resources away from practical support to local communities.

Based on polling, the overwhelming majority of indigenous voters still support the Voice. However a significant minority of grassroots elders and communities are calling for a No vote, concerned that the initiative may undercut efforts to progress Treaty and truth telling, or deny effective representation to smaller language and cultural groups.

Many major corporations, including Qantas, Rio Tinto and BHP, have called for a Yes vote, although other mining and pastoral companies are bankrolling opposition to the Voice. Australia’s richest woman, mining magnate Gina Rinehart, has long funded organisations opposed to Aboriginal recognition. The No campaign is also supported by organisations like “Fair Australia” and “Advance”, with extensive disinformation initiatives on social media, funded in part by evangelical Christian groups and the US-based “International Value Advisors.”

Reverberations across the Pacific

At a time Australia is seeking to extend its engagement with neighbouring Pacific island states, the prospect that Aboriginal claims will be spurned, yet again, is worrying political leaders from both major parties.

Campaigning in Western Australia last month, former foreign minister, Julie Bishop said Australia’s international reputation will be hurt by a No vote: “I have no doubt that it will be sending a very negative message about the openness and the empathy and the respect and responsibility that the Australian people have for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.”

Current Foreign Affairs Minister, Penny Wong has also echoed this concern, pledging to deliver on the Albanese government’s commitment “to implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full, and embed Indigenous perspectives, experiences and interests into our foreign policy.”

As the first Foreign Minister of Asian heritage, Senator Wong has sought to reframe Australia’s regional reputation and challenge international perceptions of deeply embedded racism. In September 2022, she told the UN General Assembly that “as Foreign Minister, I am determined to see First Nations perspectives at the heart of Australian foreign policy.”

Last March, Wong appointed Justin Mahomed, a Gooreng Gooreng man from Bundaberg, as the first Ambassador for First Nations People. Mahomed now heads the Office of First Nations Engagement within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, with the challenge of “embedding First Nations perspectives into Australia’s foreign policy”, “enhancing Australia’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific Region” and “progressing First Nations’ rights and interests globally.”

He faces a challenging task, given that Australian foreign policy often prioritises global geopolitical interests over regional concerns about decolonisation and the right to self-determination for indigenous peoples.

Three weeks after the Voice referendum, Prime Minister Albanese will travel to Rarotonga for the Pacific Island Forum leaders’ retreat. Facing contentious debates aplenty – over AUKUS, COP31, and Australian support for Japan’s Fukushima ocean dumping – a No vote on indigenous rights will not help Australia’s claim to be part of the Pacific “family.”

3 Comments on “Voice. Treaty. Truth”

Comments are closed.