By Nic Maclellan

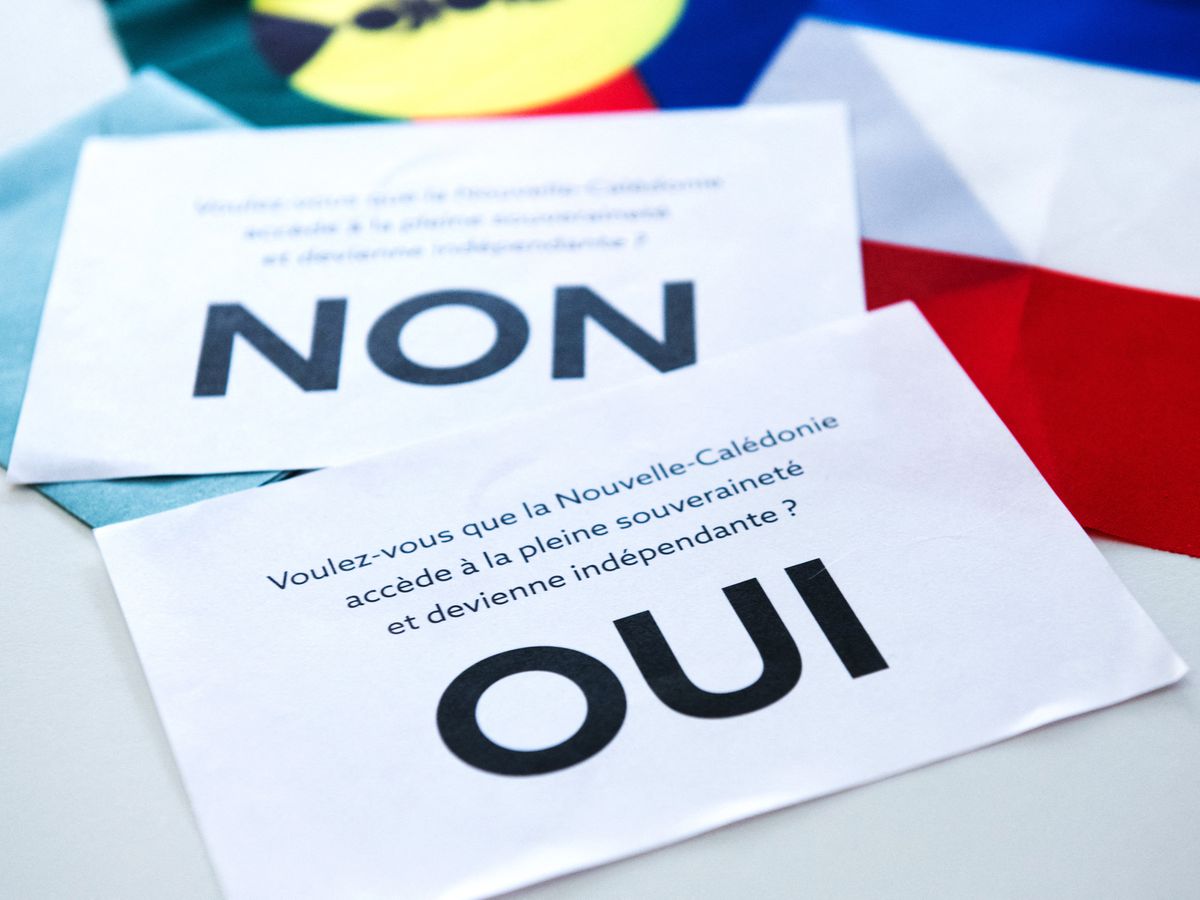

New Caledonia’s third referendum on self-determination under the Noumea Accord has returned an overwhelming majority against independence: 96.5% of people who went to the polls voted No to independence, with only 3.5% voting Yes for an independent and sovereign nation. However, this bald figure is not a true representation of sentiment amongst New Caledonians, with tens of thousands of indigenous Kanak and other independence supporters refusing to participate in the vote on 12 December.

Turnout for the referendum nearly halved in comparison to previous votes in November 2018 . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...