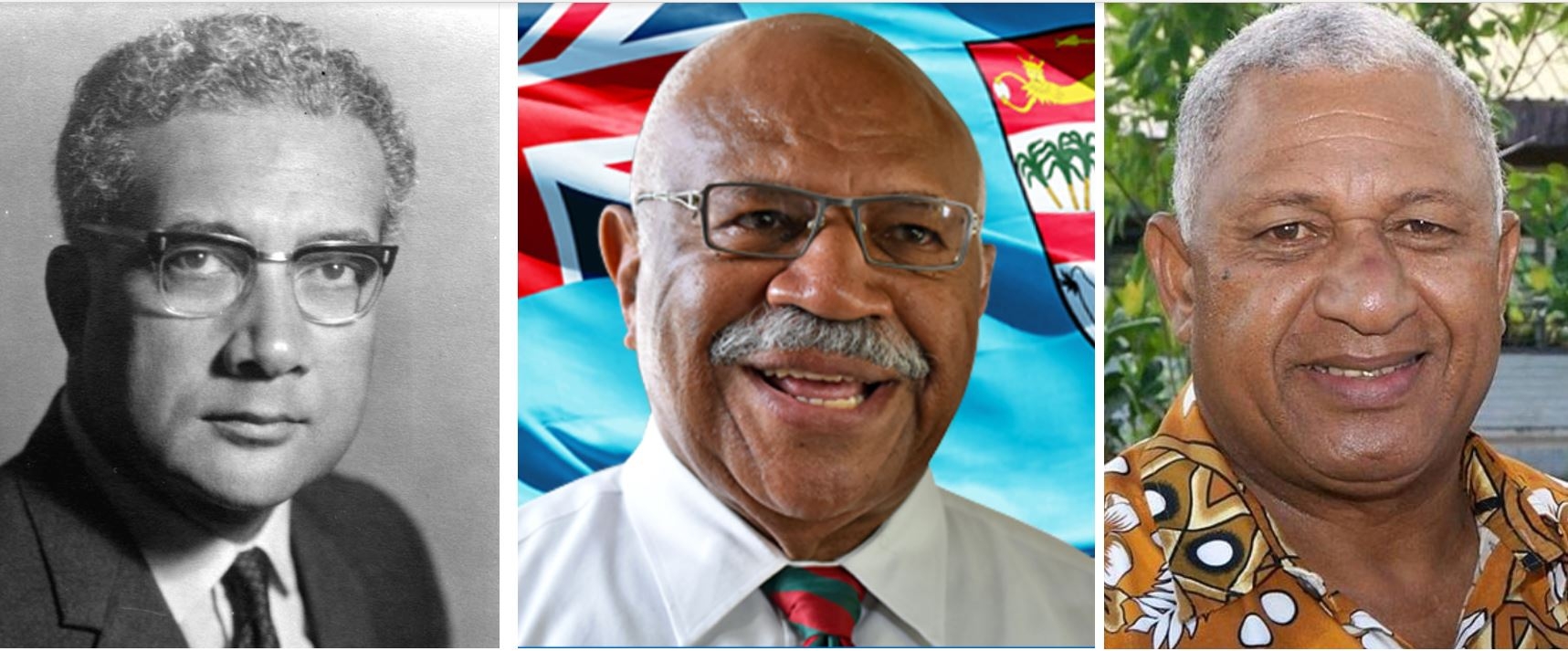

In 1965, buoyed by the outcomes of the constitutional conference in London, the Leader of Government Business in Fiji’s colonial government, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara sent a cable home: ‘Ni yalovinaka ni kakua ni taqaya, na veika kece koni taqayataka e sega ni yaco, sa nomuni na lagilagi. [Do not be concerned. All that you were concerned about did not materialise. The victory is yours].’

Those poignant words were captured by renowned Fijian historian and author, Professor Brij Lal in his book A Time Bomb Lies Buried – Fiji’s Road to Independence, 1960-1970.

Some 22 years later, Professor Lal described a public event in Suva, seven days after then Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka had overthrown Fiji’s democratically government in a coup d’état.

“A hush descended upon the lawn as the coup-maker, Lt Col. Sitiveni Rabuka appeared on the balcony. An athletic, handsome young man with a massive handlebar moustache, and dressed in powder blue safari jacket and sulu, he spoke in Fijian for a few minutes, explaining why he had carried out the coup and urging his people to remain calm. Then, with both fists punching the air, as the crowd roared approval, he said: “Sa noda na qaqa” (Rest assured, we have won).

In uttering essentially the same words two decades apart, the leaders were addressing the one issue that has plagued Fiji’s political journey for 50 years: the political paramountcy of Fiji’s indigenous community as the first settlers of the island nation.

Fiji’s political journey since independence from Great Britain in 1970 has been one of attempting to strive to strike a balance between the interests of the indigenous or iTaukei community and those of the other ethnicities that call Fiji home, in particular the descendants of Indian indentured labourers the British brought to Fiji to work sugarcane plantations during the late 1870s.

To read the whole story, login or subscribe today.