Relying on the much-touted global climate finance mechanisms provided for under the Global Environment Fund or the Green Climate Fund is like waiting for a rainstorm in a drought stricken land. One knows rain is coming but no one has a clue as to the exact time heavens will open up and for rain to fall in bucket-loads

Has the government of Fiji stumbled on the proverbial King Solomon mine with its issuance of sovereign green bond as the preferred way of accessing what has been until now the elusive billions in dollars of climate financing?

That is certainly the hope the government of Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama has pinned on this rather creative and certainly innovative way of raising capital to fund adaptation projects in an island nation that is at the frontline in the battle against the adverse impacts of climate change.

It’s surely out of the box type of thinking.

First launched in October last year, the response to these sovereign green bonds was massive: its 5-year bond for instance was three times oversubscribed. Majority of the buyers were Fiji based but a few offshore investors were among the buyers as well.

New monies from green bonds

Taking advantage of his attendance at last April’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in London, Bainimarama launch the listing of his government’s green bonds in the London Stock Exchange’s international securities market.

The plan is these bonds would generate US$50 million for Fiji’s public treasury, new monies that would otherwise had not been made available had it not for the issuance of sovereign green bonds. Money raised would for example fund the reinforcement of seawalls around Fiji’s only cannery that provides work when in full operation for some one thousand of mainly women workers.

The Fijian Government is also proposing to create stronger water and sewer utilities as well as what it is calling “energy efficient” public lightings on the five new towns it is planning to create. It is also planning to strengthen school buildings and community centres that were rebuilt after they were destroyed by Cyclone Winston in February, 2016. Winston was the strongest ever-tropical cyclone to make landfall in the southern hemisphere on record.

The gains are easy to see. One thousand workers, 90 per cent of them women have security of work because the cannery – their employer – can continue to operate for 20 or 50 more years due to the reinforced seawalling that was funded by money raised through green bonds. Thousands more dollars would be saved from a public utility that is not easily destroyed whenever a natural disaster strikes.

If no green bonds were issued, these public projects would have been funded from the normal operational expenditures of government, hard pressed as they are already with the ever mounting debts to settle and almost infinite list of public initiatives to fund.

In Fiji’s case, there is a runway NCD public health crisis where it is estimated that 1 in 3 people in Fiji suffer from. Education and capital projects of road and bridges maintenance or construction are never ending.

Besides, relying on the much-touted global climate finance mechanisms provided for under the Global Environment Fund or the Green Climate Fund is like waiting for a rainstorm in a drought stricken land. One knows rain is coming but no one has a clue as to the exact time heavens will open up and for rain to fall in bucket-loads. Small island states especially of those in the Pacific have complained long and hard about waiting for those funds to ‘rain in bucket-loads.’ Not only do they have to work through layers upon layers of bureaucracy, but waiting for the actual money to be released once approvals have been given is just another long, frustrating story.

Interests grow on green bond

As shown in Fiji’s case, issuing sovereign green bonds increases the funding pie, as it were. Now private sector money can flow into the public funding pool, providing yet another new source of finances for public agencies. It is indeed a classic example of public private partnership.

So can green bond financing also work for the other islands of the Pacific that are also at the forefront of the battle against sea level rise and adverse weather conditions? The answer from proponents of green bonds like the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation is a resounding yes.

World Bank expert on green bond Aaron Levine confirmed in our story on page 25 that interests about Fiji’s incursions into the green bond market has been received from countries in the north as well as the south Pacific. Perhaps it may be worth their while for small Island states like Kiribati, the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu to study the relevance and suitability of sovereign green bonds to their peculiar needs and status.

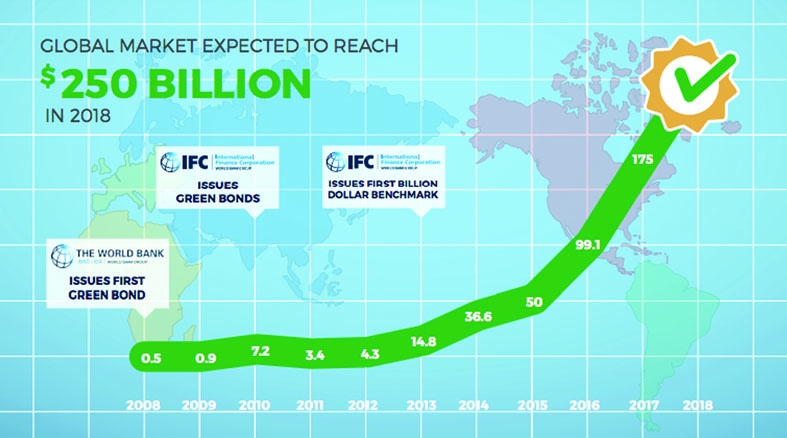

Experts say global green bond market is the way to go. There is only one way the graph is heading, and it is certainly not downward. The growth of the market has been rapid the World Bank says, with over 1500 issuances in 2017 valuing US$155.5 billion. That is a 78 per cent increase when compared to 2016.

In fact in welcoming Fiji’s foray into sovereign green bond financing, World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim said the island nation has demonstrated that emerging economies could create green capital markets. The onus will therefore be on these economies – big and small – to show political will and exercise financial prudence in accessing much needed finances in a phenomenon that they didn’t cause but are destined to become its first casualties.

One Comment “We say”

Comments are closed.