The year 2025 marked yet another period of political turbulence in Papua New Guinea. No fewer than eight motions of no-confidence were lodged against Prime Minister James Marape, two of which were eventually tabled and defeated. Over the same period, the parliament was recalled after an adjournment widely viewed as a tactic to avoid a vote; the constitution was amended to introduce a new 18-month grace period; and the Supreme Court delivered a series of significant rulings concerning parliamentary procedure.

One of these rulings addressed the constitutionality of the new 18-month grace period, which the Supreme Court upheld. Although this decision may provide some stability ahead of the 2027 elections, with roughly 18 months remaining in the current parliamentary term, political uncertainty persists. The opposition leader has already signalled their intention to challenge the Speaker’s refusal to accept the eighth motion of no confidence submitted in November 2025, casting doubt on whether this ruling will translate into sustained stability.

These developments reflect a longstanding debate on the separation of powers. Although the Constitution enshrines a separation of powers, the Supreme Court is repeatedly drawn into the affairs of the parliament, especially when disputes arise over parliamentary procedures. Section 134 of the constitution protects parliamentary proceedings from judicial scrutiny, yet the same provision also contains a critical exception: where the constitution or an organic law prescribes a specific parliamentary procedure, that is, where the matter falls within “Constitutional Laws”, the courts may intervene if that procedure is breached. Consequently, the central legal question in most references and applications is whether the disputed procedure is prescribed by a Constitutional Law or merely governed by the parliament’s standing orders.

The events of 2025 illustrate broader features of PNG’s political culture. As my recent paper argues, PNG’s politics has become increasingly litigious because the institutional dominance of the executive leaves the parliament, and especially the opposition, too weak to check government power. The executive dominates parliament through coalitions, elects compliant speakers (usually from the leading coalition party), dominates the Parliamentary Business Committee (PBC), and uses adjournments strategically to avoid motions of no-confidence. These coalitions are not held together by shared ideology or coherent party platforms but by political resources: control over District and Provincial Services Improvement Program (DSIP/PSIP) funds, the distribution of ministerial portfolios and the allocation of major national projects to constituencies.

This executive dominance has profound consequences. The opposition rarely has the numbers to prevent constitutional amendments, such as the amendments to the Constitution that introduced the new grace period. Unable to prevail on the floor of the parliament, opposition MPs increasingly turn to the courts. However, the Supreme Court has not consistently articulated a clear view about when it may intervene in parliamentary affairs.

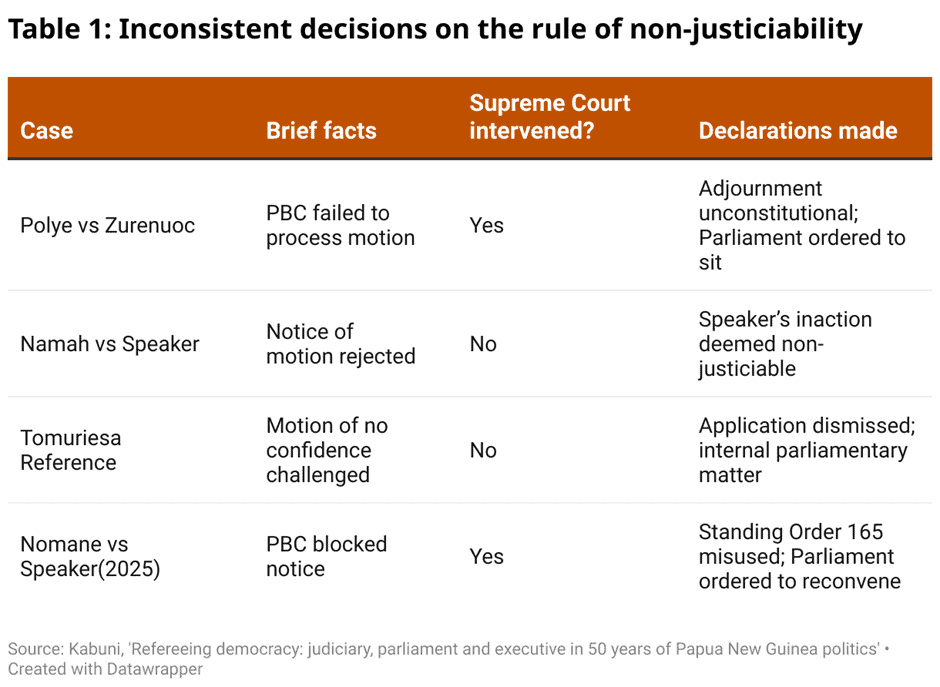

To illustrate these inconsistencies, my paper examines seven major cases concerning parliamentary procedure and the appointment or removal of prime ministers. Four of these cases are reproduced below in Table 1.

Analysis of these cases reveals a fragmented judicial pattern. Despite similar factual circumstances, the court has reached divergent conclusions about its ability to intervene. The four cases in Table 1 all involved allegations that the speaker or the PBC delayed or rejected notices containing motions of no-confidence before parliament adjourned. In two instances, the court ordered the parliament to reconvene (2016 and 2025); in the other two, it held that the decisions were non-justiciable (2021 and 2024).

Unsurprisingly, these inconsistencies have produced contrasting political reactions. Opposition MPs interpret judicial intervention as a necessary safeguard against executive dominance, while government-aligned MPs warn of judicial overreach. Following Polye v Zurenuoc (2016), for example, lawyer and Morobe MP Kelly Naru cautioned that the court risked encroaching on the parliament’s constitutionally protected domain.

The resulting ambiguity is readily exploited: MPs and lawyers cite conflicting precedents, speakers and PBCs use procedural tools to delay or block no-confidence motions, and citizens offer competing constitutional interpretations on social media. In a system defined by frequent motions of no-confidence, such uncertainty undermines the development of predictable parliamentary rules and weakens limits on the powers of the speaker and the PBC.

A more principled and consistent doctrine of non-justiciability is therefore essential. The supreme court should clarify which parliamentary procedures, especially those prescribed by Constitutional Laws, are subject to judicial scrutiny, and identify the circumstances in which intervention is warranted.

The court has itself observed the growing tendency of the executive to “bulldoze” constitutional amendments through a weak and compliant parliament and has warned against use of the parliament as a “mere rubber stamp”. Judicial intervention might sometimes be necessary to correct executive overreach, especially when the opposition lacks the numerical strength to perform its constitutional functions.

Ultimately, however, the court cannot substitute itself for the parliament. The primary responsibility for holding the executive to account lies with the legislature. A coherent and clearly articulated doctrine of non-justiciability would help restore this balance by ensuring that the supreme court intervenes only when procedures of parliament are prescribed by Constitutional Laws, while preserving parliament’s institutional autonomy.

Disclosure: The author wishes to thank the Development Policy Centre for supporting the open-access publication of the journal article, ‘Refereeing democracy: judiciary, parliament and executive in 50 years of Papua New Guinea politics’, through its Pacific Research Partnership Program.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy

Centre at The Australian National University.

Michael Kabuni is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University.