By Carina J. Fearnley, University College London

COVID-19 alerts and warnings can be better developed by bringing together lessons learned from natural hazards like volcanoes.

Just a year after COVID-19 was identified, the world’s pandemic warning system was deemed a failure by both the World Health Organisation and its independent panel, which found the world was not prepared for what lay ahead, despite the warnings.

There are still no standardised alert systems for viral threats that cut across borders, but many lessons can be learned from the management of other hazards and threats. Warning systems for volcanoes are well established, and can provide best-practice ‘lessons’ for the development of much-needed pandemic-alert systems at all scales.

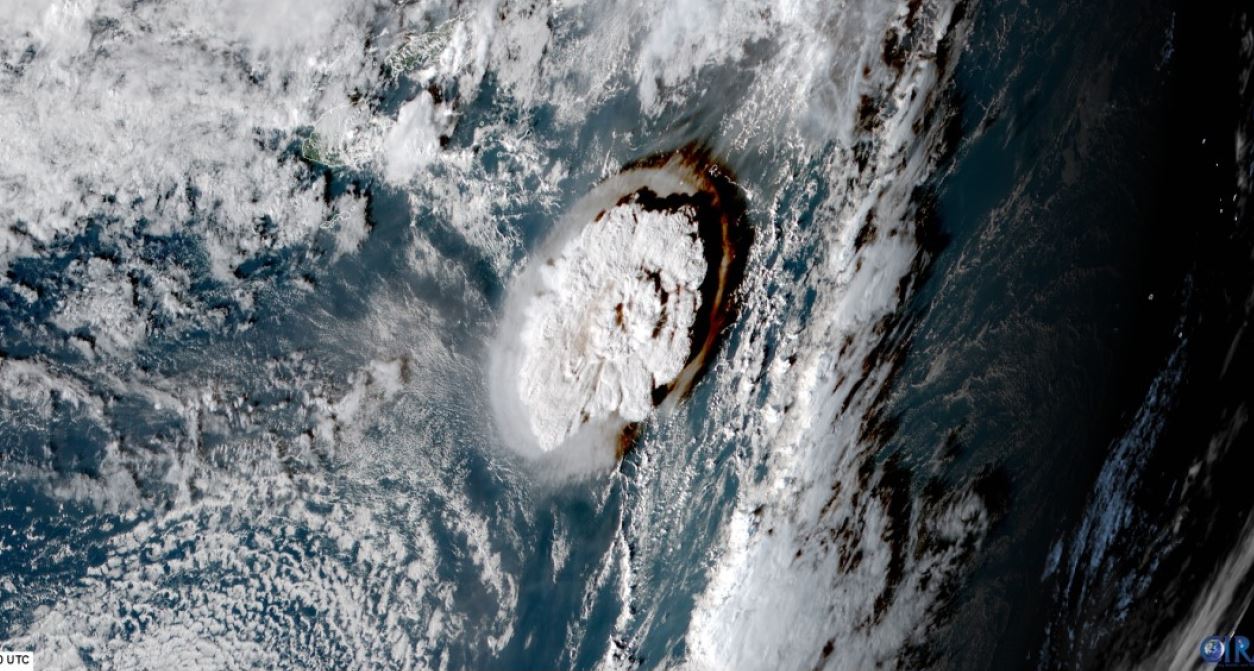

Volcanoes have the most diverse range of any hazard. They are subject to one of the world’s most frequently used warning systems, which consists of more than 80 volcano observatories that have been reviewed and improved to enhance their effectiveness over decades.

Though pandemics unfold differently to volcanic crises, volcanic eruptions involve many of the same issues. Scientific uncertainties, large at-risk populations, different industries, government bodies and non-profit organisations are all involved. We do not have time to reinvent the wheel and fine-tune global health warnings.

Volcanoes are incredibly complex and require constant anticipatory monitoring. It is often too late to evacuate the surrounding region once a volcano erupts, when pyroclastic flows at temperatures over 1000 degrees Celsius can travel at the speed of a jet plane.

Volcanologists use a wide range of monitoring equipment to detect the movement of magma under the earth, the movement of the ground as the magma rises (ground deformation), gas emissions (gas trapped in the magma escaping to the surface) and water chemistry (mixing of the magma with groundwater). All this data provides clues about what a volcano is doing, but combining it is extremely challenging, so alerts are often issued in anticipation of potential activity. Scientists, emergency and disaster specialists, local communities and different levels of government must cooperate well to prepare and immediately respond.

The 1985 tragedy of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia, where warnings were not acted upon, resulted in more than 23,000 deaths. The White Island Whakaari volcano eruption in 2019 killed 22 people who were part of a tour group exploring the New Zealand island. These events taught the hard lesson that, despite improvements in scientific data and warnings, tragedy can still result if no action is taken in response.

The level of monitoring and warning we apply to volcanoes is needed to detect future pandemics. Most pandemic warnings focus on the event once it has spread to the community, but a radical shift to anticipatory warnings is needed. Too little attention is paid to the prevention of circumstances that increase health risks, such as deforestation, land-use change, intensive livestock production and climate change.

Many nations have devised alert-level systems to protect local populations during the shift from full COVID-19 lockdown precautions to normality. To be effective and timely, these alerts must be embedded in an extensive system of observation and communication that integrates different expert cohorts, tipping points, communication channels and iconography.

Existing warning systems are already used for hazards and threats such as severe weather, tsunamis, terrorism or chemical accidents. They often follow a traffic-light colour structure or numerical order (as commonly used in military contexts) and are standardised at national and international level. Numerous alert systems were devised or used during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no comparative study to establish which were most successful, and why. However, there have been some success stories seen in New Zealand, South Africa, and South Korea amongst failures as seen in the UK, and the U.S.

COVID-19 alerts and warnings can be better developed by bringing together lessons learnt from the warning world from a range of hazards and threats to review elements of what makes warnings succeed and what makes them fail. There are three key lessons.

Firstly, warning systems can be effective in generating general awareness and acting as triggers for initial communication, policy and action. But they require everyone in the scientific and decision-making communities to understand and effectively communicate all relevant information both ways.

‘Mind the gap’: this phrase bellows out of most London Underground stations but captures the essence of the second key lesson learnt — the challenges of negotiating gaps between hazard and risk information. Alert levels can change due to the perceived threats at hand, but the decision to progress or downgrade these levels can be challenging due to difficulties in interpreting scientific data and understanding what response is required.

Finally, the decision to move between alert levels requires negotiations of perceived political, livelihood and environmental factors rather than just evaluation of the scientific data.

Standardisation of alert systems is also vital to convey information across communities, but systems need to be designed according to national and international policies while considering local threats (see Figure 3). This is very hard to achieve due to the diversity and uncertain nature of hazards across different geographical areas, as well as cultural and political factors. But many volcanic communities globally can do this for volcano ash hazards, particularly in the context of aviation hazards.

Decision-makers at all levels have often failed to recognise or act upon early warnings. This lack of action is a huge problem for all hazard and threat warnings, and will inevitably play a role in the next big pandemic, which will arise sooner than we might think. Plenty of examples exist of excellent science communication but lack of action.

Action depends on collaboration across the many silos that exist in organisations, disciplines and hazards, and the newly founded UCL Warning Research Centre aims to foster such collaboration. We can draw on hard lessons learnt from other hazards and threats to be more resilient to single, multiple and cascading hazards.

It is action that is needed the most, yet the ability to make the necessary changes remains our biggest challenge, especially if we don’t go beyond the silos.

Dr Carina Fearnley is Director of the UCL Warning Research Centre, and Associate Professor at the UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies. She is an interdisciplinary researcher, drawing on relevant expertise in the social sciences on scientific uncertainty, risk and complexity to focus on how natural-hazard early-warning systems can be made more effective.