OVER three decades in the United Nations system, from village classrooms in Fiji to ministries in Africa and labour institutes across Asia, I have heard the same question: how do we build an economy strong enough to keep our people?

Across the Pacific, however, a quiet resignation has set in. Many now see the loss of teachers, nurses, tradespeople and young families as the inevitable fate of small island states, and rising remittances as an acceptable trade-off. Labour mobility is shifting from a safety valve to an unofficial development model. Global experience shows the danger. In Manila, Kathmandu, Kingston or Suva, I have never seen a country build lasting prosperity on the earnings of its absent citizens.

The Pacific is at a turning point. Remittances are climbing across Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu, Kiribati and Tuvalu, while domestic capacity is thinning just as fast: fewer teachers in classrooms, fewer nurses in clinics, fewer skilled workers in key sectors, fewer young people imagining a future at home. I see rising remittance dependence not as a trend, but as a structural warning. The real question is whether Pacific countries can retain enough people, skills and confidence to sustain viable economies.

I want to make a simple point: remittances help families, but they are not development. Without urgent action to rebuild domestic capacity, the Pacific risks sliding into a remittance-dependence trap that no country has ever escaped.

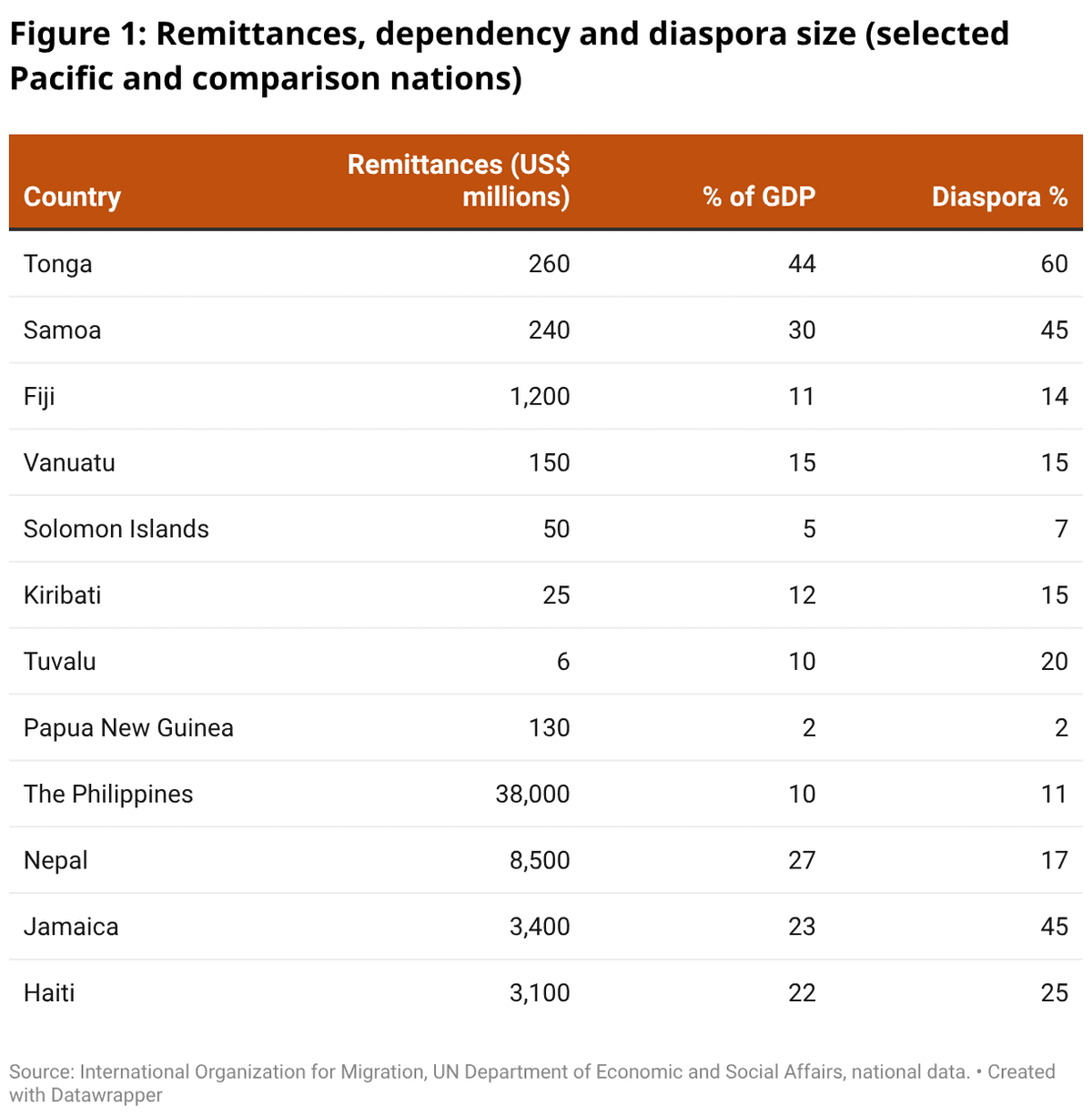

The Pacific now has some of the highest remittance-to-GDP ratios in the world. In several countries, inflows rival or exceed tourism, agriculture, fisheries and even aid. Tonga and Samoa sit among the world’s top remittance-dependent economies. Fiji now receives over $USD1.2 billion – around 11 per cent of GDP. In many small island states, 20–50 per cent of citizens live abroad.

Remittances have become the region’s economic oxygen. Their value is undeniable. But so are their limits. High remittances consistently correlate with labour shortages, declining productive capacity, skills loss, rising dependency and continued outmigration.

Decades of research from the World Bank, the International Labour Organization, the Asian Development Bank and academic studies show the same conclusion: remittances offer consumption relief, not structural transformation. They support household income, education, and recovery after disasters, but they do not create industries, build institutions, expand the fiscal base, raise productivity, or generate broad-based employment. A dollar sent from Sydney or Auckland helps a family in Nadi or Apia, but it does not build a firm, a sector or a long-term job.

If remittances were a development strategy, Tonga would resemble Singapore and Nepal an Asian tiger. They do not. The global lesson is unmistakable: no country has ever moved from low-income to high-income status through remittances.

Fiji’s remittance boom is unfolding alongside something more worrying: a rapid erosion of domestic human capital. More than 114,000 people have left in six years, the equivalent of emptying a major town, while the economy continues to expand. This is not a crisis of patriotism; it is a crisis of capacity. Labour shortages now affect nearly every sector: education, health, construction, tourism, agriculture and the public service.

To cope, Fiji increasingly recruits workers from Bangladesh, the Philippines, India and Indonesia. They contribute significantly, but the risk is structural: locals leave; foreign workers keep the economy running. What Fiji lacks is not ideas, but a coherent labour-market strategy linking wages, migration, skills, tertiary education, private-sector demand and institutional reform.

As Adam Tooze argues in his 2025 Foreign Policy article The end of development that economic outcomes are ultimately political outcomes. People do not leave countries; they leave political economies where institutions feel opaque, opportunities feel limited, wages lag behind living costs, public services are stretched, meritocracy feels uncertain and the future feels narrower than elsewhere. Remittances can mask these pressures, reducing the political urgency for reform.

Small states cannot stop migration, but they can reshape the reasons people leave: make work pay with evidence-based wage reforms; promote meritocracy and institutions of fairness; institute national skills compacts; turn remittances into investment through diaspora bonds and matched savings schemes; create domestic jobs through sector strategies for agricultural modernisation, blue and green economy initiatives, ICT-enabled services and creative industries.

The real test of leadership is not whether people leave, but whether staying remains a dignified, rational and hopeful choice. Remittances keep households afloat, but only domestic opportunity keeps a country standing. When people lose confidence in their political economy, they migrate; when they believe in tomorrow, they invest in it. That belief, not GDP or inflows, is the real foundation of development.

The Pacific is now at that crossroads. We can treat rising remittances as success and the loss of workers as destiny. Or we can choose the harder path: rebuild institutions, reward merit, lift wages, invest in skills and expand real opportunities at home. Countries like Singapore and Mauritius did not develop by exporting people. They developed by giving people reasons to stay.

A future worth staying for is not a miracle. It is a choice, and it is still within reach.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. Dr Naren Prasad is an economist and Head of Education and Training at the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva. He has held senior roles with UN agencies including UNESCO and UNRISD. He holds a PhD in Economics from Université Panthéon-Assas (Paris, France).