(Natori, Japan) When a magnitude-9 earthquake hit northern Japan on March 11, 2011, businessman Naomitsu Kakui was driving in Sendai City. The shaking was so intense, he stopped where he was, got out of his car and crawled to the side of the road.

His thoughts turned quickly to his family, who lived in Natori, a seafront city neighbouring Sendai, over 10 kilometers away. He tried to get home to them, but the roads were blocked.

One hour and three minutes after the earthquake, a series of tsunami waves started to crash into Natori and other parts of Japan’s Pacific coastline. Kakui’s wife and two children were able to make it to higher ground and safety. However, his father and mother perished in the disaster.

Across Japan, more than 19,700 people died. The tsunami triggered a triple meltdown of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. Japan, and her Pacific Island neighbours, are still grappling with the consequences of that accident, and how to deal with the radioactive wastewater it generated.

In Natori, more than 700 people died as a result of the earthquake and tsunami.

The signs of the Great East Japan Earthquake are still visible everywhere here. There are memorials and a museum (dedicated to the disaster and recovery). Apartment blocks close to the ocean have external staircases to their roofs, which act as tsunami escape routes and are accessible to all. Plaques marking the height of the 2011 tsunami waves are visible from the moment you leave Sendai airport, which itself was inundated by the huge tsunami waves. Areas once populated by houses are now empty fields, as rebuilding has been prohibited in certain areas. The dyke running along the coastline has been raised to 7.2 metres in height.

As a community leader, Kakui is determined to ensure that people learn from what happened to his hometown.

There was no tsunami alert or alarm in Natori on the day of the Great East Japan Earthquake due to an electrical failure in the municipal office.

Speaking beside four tall black memorial stones standing sentinel near the Natori shoreline, Kakui points out that one of them commemorates an earthquake in 1933. No-one died, but the marker warns of the danger of tsunamis, which in that case roared kilometers inland. He says people had forgotten about the marker, and it was only rediscovered in the aftermath of the 2011 catastrophe. It now stands flanked by stones commemorating locals lost at sea, and at war. If only we had learnt from our ancestors, he says.

Kakui believes people were also complacent, having been warned about the possibility of tsunami waves after an earthquake two days before, on March 9th.

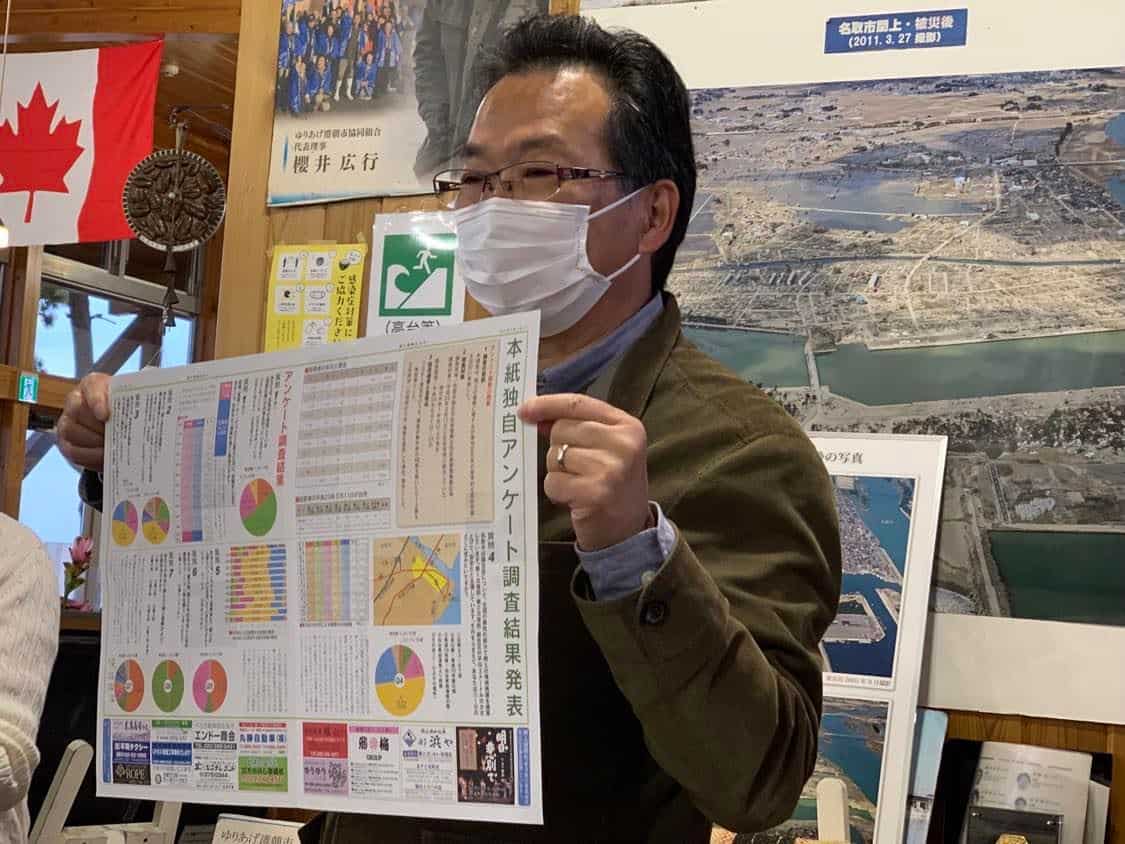

After the March 11 disaster, Kakui and his family spent two years in temporary accommodation before moving to Sendai City. In that time he started a community newspaper, to share information about the government response to the event, survey residents about their views on rebuilding and reconstruction, and eventually, in 2019, “announce that we had achieved recovery.” That newspaper was particularly important for the area’s older residents, he says, who not only read it, but keep their copies. Kakui says the lessons from 2011 are clear. Move quickly, do not hesitate to evacuate, and do not go home to collect items if evacuation is necessary.

In the Pacific, Japan’s experience is but one chapter in a series of devastating events. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that decimated communities in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand, and closer to home, the Aitape, PNG (1998) Gizo, Solomon Islands (2007) and Samoan tsunamis (2009), have increased our awareness of tsunami response. The lessons of Sendai, and the conviction of survivors like Naomitsu Kakui that more people could have been saved it if were not for complacency, are a timely reminder for all of us.