Pacific researchers assessing the wellbeing of tourism-reliant communities in Fiji, Samoa, Vanuatu and the Cook Islands amid the COVID-19 pandemic have found these communities are mainly resilient in the face of adversity.

Professor Regina Scheyvens and Dr Apisalome Movono’s ongoing study “Measuring the Well-being of Tourism-Reliant Communities in the South Pacific during the COVID-19 pandemic” has involved online surveys and in-person interviews with participants ranging from “coastal mainland communities who had leased their land to a large resort, to small communities mainly running their own tourism ventures in coastal or off-shore island locations,” says Professor Scheyvens.

Six types of wellbeing were analysed: financial, mental, social, physical, spiritual, and environmental. Financial stability was seen to have the most impact on Pacific peoples’ wellbeing. The 2020 survey showed that over 70% of respondents’ household income had greatly reduced and more than 80% of participants who owned businesses encountered major decline in earnings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the overall outlook on income generation remains a significant concern as most respondents illustrated that their financial wellbeing “strongly declined” in the absence of tourists during COVID.

Both researchers believe governments and development partners should effectively alleviate such financial concerns. “There is a place for governments and development agencies to provide immediate support for those people who have struggled without their usual tourism income for so long,” Scheyvens told Islands Business.

Professor Scheyvens shared her concern about some Pacific tourism workers in the long run. “We are worried, for example, that the main means of support offered to Fijian workers was to allow them to access their FNPF (superannuation) savings,” she says. “This has undermined their future financial wellbeing as many will now have little available from FNPF in retirement.”

Scheyvens said: “Stronger policies and strategies [need to be put] in place to support the rights, conditions and security of tourism employees such as forms of income protection insurance, subsidised by employers, and government.”

Dr Movono emphasised that “unions must be empowered and provided the freedoms and rights they deserve to support their members – conversations can be held on building a tourism worker resilience/provident fund. The fact remains, there will be future shocks and we must move beyond reimagining to actually transforming the way we do tourism in the Pacific.”

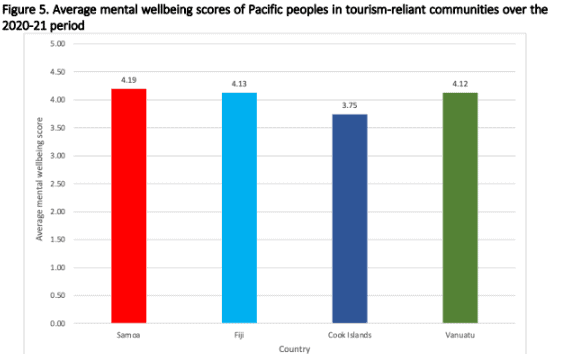

Mental wellbeing

Cook Islands, in particular, showed lower mental wellbeing compared to other countries in the study. Scheyvens attributes this to the Omicron outbreak in New Zealand which was spreading fast mid-January this year. “We are aware that some people in Rarotonga were naturally very worried about the border opening at the time thus we think this largely accounts for the lower mental wellbeing numbers in the Cook Islands,” she said. Despite that, most respondents stated that the pandemic gave them a chance to focus on their mental health. One female business owner in the Cook Islands shared: “For the first time as a businessperson you had a forced pause on your business. You had the opportunity to step back and analyse…such as whether this was the future you wanted.”

Spiritual wellbeing

Spirituality acted as a “safety net” for most respondents which influenced positive wellbeing during the pandemic, says Dr Movono. “People were telling us that they were able to cope because they were praying together more, being supported by the church and the community,” he says. “It was imperative that we considered it [in the research] because spirituality is embedded and a significant part of Pacific peoples and their identity which is often ignored from western framings of wellbeing.”

Physical and environmental wellbeing

Physical and environmental wellbeing go hand in hand, the research shows. “We were really pleased to see strong agreement from respondents that their physical wellbeing had improved during the pandemic period,” says Scheyvens. “This was due to people doing more physical work to get food i.e., gardening, farming and fishing, but also due to them saying they were eating a better quality of food because they had more local produce available, either grown by themselves or at good prices, and they had more time for exercise.”

In April, Dr Movono spoke with a tourism worker in Fiji who returned to work at a large resort. “The gentleman said that he had lost heaps of weight and felt a deeper sense of awareness about healthy lifestyle choices, having a garden and pigs. However, he was happy to back in his role as “an ambassador of his tribe to the world (as a tourism worker)” but was also conscious that he could slip into old habits given the difficult hours and lifestyle that staff at hotels often endure,” Movono said.

“Many people are keen to be working back in the tourism sector in Fiji and Cook Islands, but across all four countries, they expressed a desire for a more work/family/life balance in future,” says Scheyvens. “Our research assistant in Vanuatu said people had told him it had taken them months of hard work to establish really good gardens and they didn’t want to give that all up and let the crops rot because they got too busy with their paid jobs again.”

“We need to start having serious conversations about how to sustain the well-being of Pacific people – especially when the environment provides much more than money and hotels, contributing to people’s wellbeing in a complex way,” says Dr Movono.

He adds: “The Vanua (or Whenua) has a special place in Pacific societies and because people have been able to reconnect with their customs and Vanua, they have a greater appreciation for their customs and want better outcomes from tourism. One Fijian elder stated that he “wanted tourism to complement their way of life, not take over it – a wise but very timely advice for how to build tourism forward better.”

Related stories: Fiji’s tourism comeback