One of Scott Morrison’s biggest announcements from last August’s 51st Pacific Islands Forum was to double the number of Pacific workers in Australia by March 2022 to at least 25,000. The government has come close to hitting that target, saying that as of last month, 23,000 workers were in Australia under the two PALM schemes, the multi-year Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) and the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP).

Which countries are these Pacific workers now from? What is the relative size of the two schemes? What is the gender composition of the workers, and what sectors are they working in?

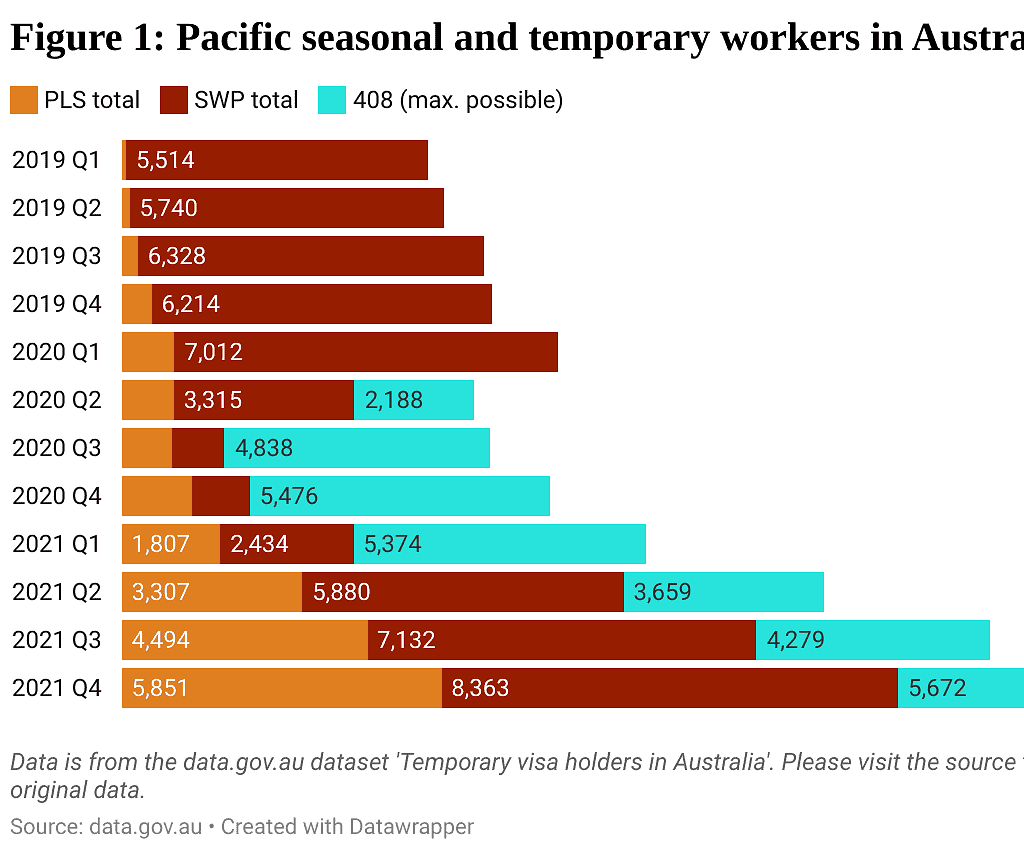

These questions are tricky to answer due to COVID-19, which has resulted in longer stays and the introduction of the COVID-19 Pandemic Event (408) visa. Between May 2020 and December 2021, 7,225 Pacific workers transitioned to the 408 visa, the vast majority of them SWP workers. Unfortunately, while we have data on the number of SWP and PLS visa holders in country, we don’t know how many 408-visa holders are still in Australia. An estimate on the number of Pacific workers in Australia is given in figure 1, which shows that there were almost 20,000 by the end of December last year. Some of the 408 visa holders would have returned home, so this is an overestimate, but not a huge one. We know that between August 2021 and February 2022, only 601 SWP workers and 37 PLS workers returned home.

We can also look at arrivals. Between April 2020 and February 2022, 6,547 PLS workers and 15,805 SWP workers arrived in Australia. Between April and August 2020, during the temporary pause on worker arrivals, the average was just 75 a month. From September 2020 to March 2021 the average was 598 a month. And from April 2021 to February 2022, the average was 1,617 a month. An assumption that this average continued for March and April, and that the number of returns remained fairly low, is consistent with the number of workers in country in April hitting 23,000 or even higher.

Several countries have gained from PALM growth, but some have missed out, and a few have even seen declines. For the SWP, our analysis includes both those currently in Australia on an SWP visa, and all 408 PALM country visa holders. (Excluded are the not insignificant number who have moved onto bridging visas after making an asylum claim.)

Vanuatu has retained its dominant position in the SWP, and Tonga has slipped marginally. The big SWP gainer has been Samoa, whose share has increased from 5% at the end of 2020 to 16% at the end of 2021. The big loser has been Timor-Leste, which was excluded from the SWP restart because of COVID-19 outbreaks, and which has plummeted from third to fifth slot, with its share falling from 17% to 5%.

Samoa has also been the biggest gainer from the PLS expansion, its share doubling from 13% to 25% over the course of a year. Solomon Islands has also done extremely well, becoming the biggest source country, with a 29% share. The Solomon Islands government has therefore well exceeded its target of 1,150 PLS workers by 2023, overcoming its historic under-representation in Australian labour mobility programs. Fiji’s PLS numbers have grown, but its share has halved.

The figure below shows combined numbers for the PLS and SWP. Vanuatu now has about one-third of all workers across the two schemes, Tonga and Samoa about one-fifth each, Solomon Islands 13%, and other countries 5% or less. Of the big four, Vanuatu has maintained its combined share, Tonga has lost it, and Samoa and Solomons have gained it.

Some of the national growth rates are truly phenomenal: Samoa has seen growth of 540%, Solomons 666%. But other countries have missed out. We have already mentioned Timor-Leste, but PNG numbers remain small, with growth of only 20% and total numbers of less than 200.

The SWP remains dominated almost entirely by horticulture. The largest industry for PLS workers remains meat processing (67%) with horticulture and agriculture (24%) in second place. All other sectors are tiny: third is aged care services at 2% of all workers.

As at the end of 2021, only 10% of PLS meat industry workers and 37% of horticulture workers are women, resulting in an on overall female share of the PLS workforce of about 19%: hardly different to earlier. Unfortunately, we could not obtain SWP gender data.

These figures confirm that the Pacific labour schemes have been transformed through the pandemic. The last pre-COVID year, 2018-19, saw 12,200 SWP workers arriving in Australia, and at that time the PLS had around 150 workers. Based on July 2021 to February 2022 data, there will have been another 12,000 SWP arrivals in 2021-22, but that is on top of the 6,000+ SWP workers who have stayed on using a 408 visa. In addition, the PLS has become a significant component of Pacific labour mobility, with some 6,000 workers at the end of December 2021 compared to virtually none at the start of the pandemic.

While the growth in the SWP and PLS is impressive, it is also worth noting that the share of the PALM labour force from Tonga and Samoa has increased from 33% to 40%, from 2,500 to 7,900. These two countries are already among the most remittance-dependent countries in the world, and it is not surprising that complaints have started to arise about brain drain. One Samoan recently commented on the Devpolicy blog that “we are losing a lot of skilled labour to both schemes, with many resigning from their jobs and entering into the schemes for better money. We are losing qualified teachers, nurses, chefs, and the like to these schemes.” The loss of skilled workers is one of the reasons Samoa’s government has announced a review of the programs. Local businesses are also complaining.

Brain drain complaints tend, like those of family separation, to receive less attention than worker mistreatment in Australia, but are no less serious. They are especially acute for the PLS, where employers are more likely to look for people with pre-existing skills, even in a different area. While the PALM schemes have many benefits, they are not targeted enough to countries – such as PNG and Timor-Leste – that stand to benefit the most from labour mobility opportunities but have the least access to the Australian labour market. The Pacific Integration Visa, promoted by Labor, would be much better targeted (through use of country quotas) and should be adopted by whoever wins the election.

Note: Data sources used in this article are, for arrivals, Department of Home Affairs ‘Overseas Arrivals and Departures’; for workers in-country, Department of Home Affairs, ‘Temporary visa holders in Australia’; and for PLS gender and sector composition, data was provided by Pacific Labour Facility, accurate as of 7 March 2022.

Disclosure: This research was supported by the Pacific Research Program, with funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views represent those of the authors only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. Evie Sharman is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre, working in the Pacific Labour Mobility team. Stephen Howes is the Director of the Development Policy Centre and a Professor of Economics at the Crawford School.