Commemorating the International Day Against Nuclear Tests, Fiji Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama has spoken out about the health and environmental legacies of Cold War nuclear testing in the Pacific.

As Pacific Islands Forum chair, Bainimarama said: “Our Blue Pacific continent was the theatre for some of the most powerful nuclear tests ever conducted in world history – what we consider atrocities perpetrated on our people without our consent.”

The Fijian leader presented the keynote address to open a Forum webinar for the UN International Day Against Nuclear Tests, a commemoration held each year on 29 August.

“We endured five decades, from 1946 to 1996, of more than 300 nuclear tests at atmospheric, surface and underground levels” Bainimarama said. “These were conducted on Bikini Atoll and Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands, in the Montebello Islands in Australia, near Malden Island and Kiritimati Island in Kiribati, on Johnston Atoll, and on Moruroa and Fangataufa Atolls in French Polynesia.”

He noted: “The impacts have been nothing short of devastating; from the local, regional and global fallout, to the residual contamination and radioactivity in our ocean and lagoons. From the permanent relocation of resident populations in the Marshall Islands, to the serious and lasting impacts on the health, environment and human rights of our affected communities.”

The panel discussion, facilitated by Islands Business publisher Samisoni Pareti, included Samoa’s High Commissioner to Fiji Aliioaiga Feturi Elisaia, Forum Deputy Secretary General Dr. Filimon Manoni, Ariana Tibon of the RMI National Nuclear Commission and Ambassador Flávio Roberto Bonzanini, Secretary General of the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL).

Nuclear testing and the Forum

As the Pacific Islands Forum commemorates its 50th anniversary, Prime Minister Bainimarama paid tribute to Pacific leaders who developed the 1985 Rarotonga Treaty for a South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty (SPNFZ).

“The Treaty successfully led to the permanent cessation of nuclear testing in our region in 1996,” he said. “Though a product of its time, the Treaty of Rarotonga is one of our very first and most significant achievements as a Forum family.”

In his opening remarks, Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum Henry Puna also noted that “nuclear testing was a key political driver for our Pacific Islands Forum fifty years ago.”

Puna paid tribute to “all our Forum leaders, past and present, who in unity and solidarity with those affected, have vowed never to allow these atrocities to befall our beloved Blue Pacific home again.”

Leaders such as Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, Albert Henry, and Hammer de Roburt created the Forum in 1971 because the colonial powers that dominated the South Pacific Commission refused to allow “political” issues to be discussed at SPC meetings.

Mara’s autobiography ‘The Pacific Way’ highlights the “ban on political discussion” at the South Pacific Commission, noting that “France was the most insistent on this, probably on account of its own vulnerable position in the Pacific, because of both its overseas territories there and its nuclear-testing programme at Moruroa Atoll. Economic and social issues oui, politics, non.”

The restriction on topics like nuclear testing, self-determination and political sovereignty drove the independent island leaders to meet separately from the colonial powers. Today, nuclear weapons states like France, Britain and the United States are still members of regional technical agencies like SPREP and the SPC (today’s Pacific Community), but Forum Island Countries are looking at new avenues to press for nuclear disarmament.

Ten Forum member countries have signed and ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPWN), a new global disarmament agreement that includes a comprehensive set of prohibitions on participating in any nuclear weapon activities. These include undertakings not to “develop, test, produce, acquire, possess, stockpile, use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.”

The Fiji Prime Minister said: “I am heartened by the entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons on 22 January 2021. I call on every peace-loving member of the global community of nations yet to sign the Treaty to consider doing so.”

History of Pacific protest

Even as a former naval commander, Prime Minister Bainimarama has often spoken about the health and environmental legacies of nuclear tests in the Pacific Islands conducted by the United States, France and Britain.

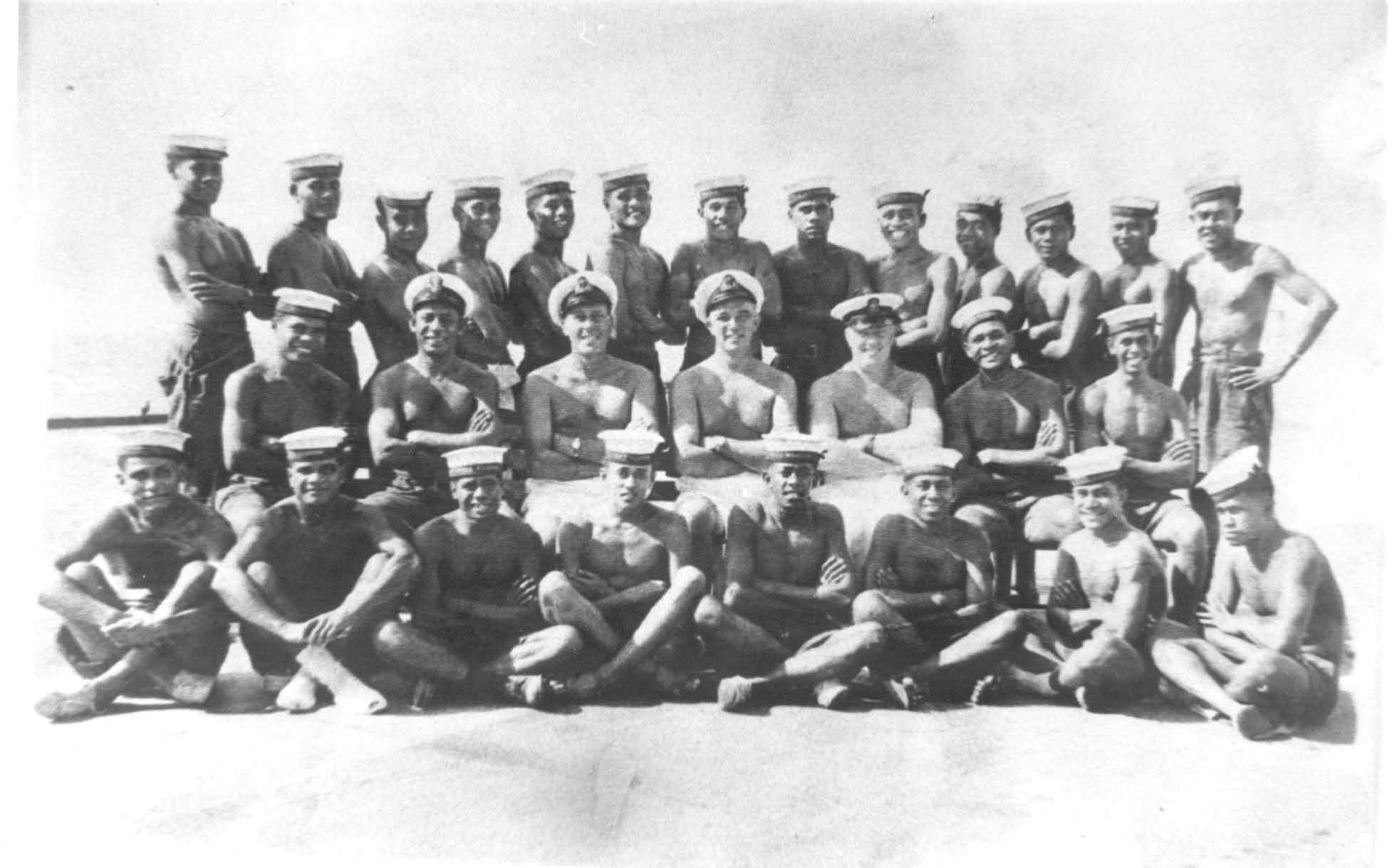

In 1957, his father Ratu Inoke Bainimarama led a contingent of 39 Fijian sailors to witness the British nuclear testing program at Malden and Christmas (Kiritimati) Islands in the central Pacific. Today, Fijian, NZ and i-Kiribati participants in the Operation Grapple hydrogen bomb tests continue to seek compensation from the UK government for the health consequences of their service on Christmas Island, after civilian and military personnel were exposed to hazardous levels of ionising radiation.

From the start of the nuclear era, indigenous peoples around the Pacific protested against nuclear testing throughout the 1950s, even under colonial administration.

One of the earliest antinuclear protests was in French Polynesia, when the charismatic leader Pouvanaa a Oopa collected signatures for the 1950 Stockholm Peace Appeal. Pouvanaa was framed, tried and exiled from Tahiti as French authorities planned to establish the Moruroa test site.

After the United States conducted the Bravo nuclear test on Bikini Atoll on 1 March 1954 – the largest ever test by the US military – Marshall Islands’ teachers, businessmen and iroij (chiefs) lodged a petition with the UN Trusteeship Council, asking that “all experiments with lethal weapons within this area be immediately ceased.”

In 1956, as the UK formally announced its series of hydrogen bomb tests at Malden Island and Kiritimati Island, Western Samoa petitioned the United Nations Trusteeship Council to halt the operation (at the time, Samoa was a dependent trust territory of New Zealand).

In 1956, customary leaders on Rarotonga raised concerns with the Cook Islands Legislative Council about proposed British hydrogen bomb tests on Christmas Island, asking “that the testing area be situated at some greater distance than the Cook Islands.”

As former Prime Minister of the Cook Islands, Secretary General Puna said that Penrhyn and other northern atolls of his homeland were affected by 1950s British nuclear testing in the nearby British Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony.

“Our people bore witness to what has been described as ‘an awesome glow in the sky’,” Puna said. “The glow was a mystery for our people in the north who sought to collect, share and feast on the fish washing up along the shorelines.”

Even with the end of atmospheric and underground nuclear testing in 1996, Forum leaders are again speaking out about the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the hazard of nuclear contaminants in the Pacific. At their recent virtual summit, Forum leaders raised concern about Japanese proposals to dump contaminated waste water from the stricken nuclear reactors at Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean.

During the Forum webinar, Secretary General Puna noted that the nuclear issue should be an ongoing priority for discussion with Forum dialogue partners.

“The nuclear threat is mutating and is now more complex than ever, including the threat of the militarisation of space,” he said. “In the current context of climate change, there is a growing trend towards nuclear energy – but friends, nuclear energy poses major risks and consequences in and of itself, including disaster related accidents.”