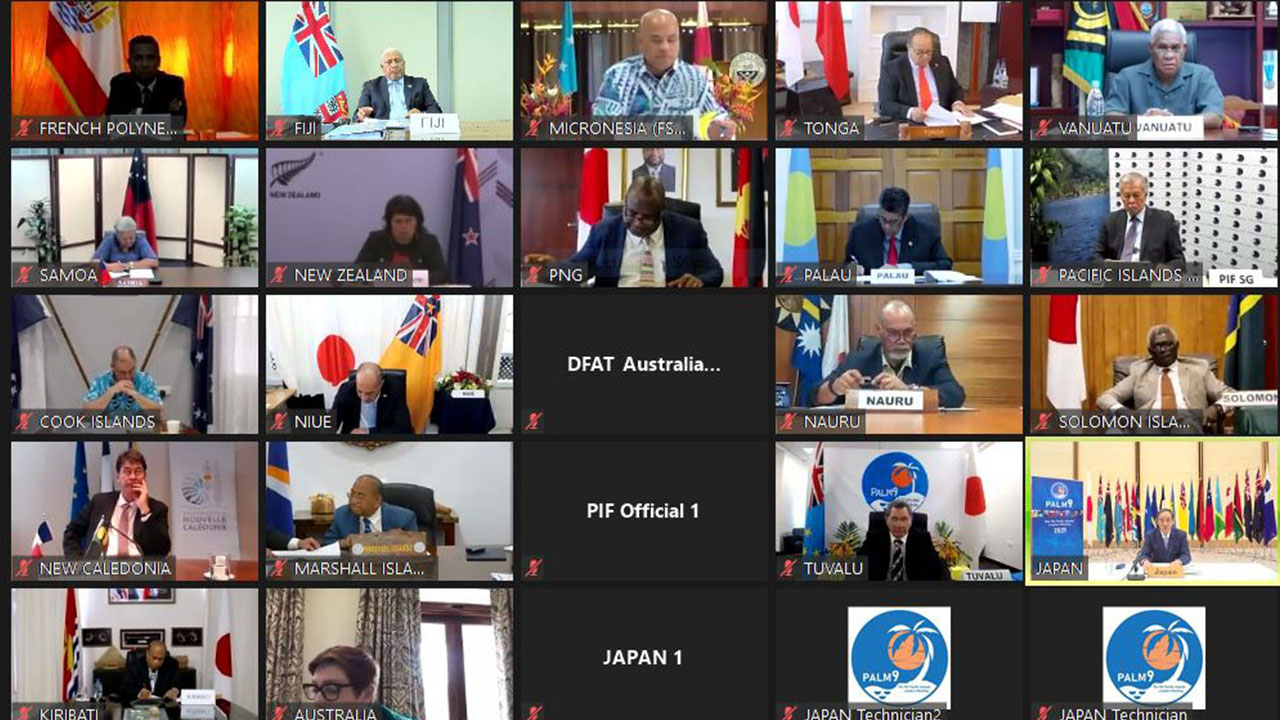

Japan’s Yoshihide Suga has announced a new “Pacific bonds” policy to strengthen cooperation between Japan and Forum Island Countries, as Pacific leaders joined the Japanese Prime Minister on Friday for an online summit – the ninth Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM9).

In line with Australia’s “Pacific step-up” and New Zealand’s “Pacific reset”, Prime Minister Suga’s “Pacific bonds” policy promises new co-operation on climate action, COVID-19 vaccinations and infrastructure funding. However this Japanese diplomatic push into the Pacific is being damaged by the announcement that Japan plans to dump waste water into the Pacific Ocean from its stricken Fukushima nuclear reactors.

On 13 April, the Suga government unilaterally announced plans to discharge more than 1.2 million tonnes of treated radioactive waste water into the Pacific, starting in 2023.

Working alongside Australia, India and the United States as a member of the Quad, Japan is seeking to promote a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” But the proposed dumping of contaminated water from Fukushima is a major diplomatic setback for Japan in the Pacific islands. Anger will grow around the region as citizens call for a stronger response from their governments.

Fukushima disaster

The waste water is currently stored in more than a thousand tanks at the site of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Three nuclear reactors at Fukushima were flooded in March 2011 after an offshore earthquake and a 14-metre tsunami hit the coast. The flooding caused massive damage to the reactors’ power supply and cooling systems, leading to the partial meltdown of the reactor cores and extensive leakage of radiation.

Since then, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) has been using water to cool overheating still emanating from the melted fuel rods, which have burned through steel containment vessels and into the concrete base of the reactor buildings. This highly contaminated cooling water is then stored in tanks at the site, many of which were hastily constructed and already have a track record of leaking. Now, with more than a hundred tonnes of water collected every day, storage space is running out.

Japan proposes to dump this contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean after treatment through an Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS). The Japanese government has acknowledged that this treated waste water will still include radioactive tritium, but argues this will be diluted by the vast waters of the Pacific to reduce environmental damage. However scientists from the US Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution report that, beyond tritium, the treated waste water will include isotopes such as carbon-14, cobalt-60, and strontium-90, which have vastly different toxicity and can be incorporated into marine biota or seafloor sediments. A February 2020 government report on the ALPS process acknowledges that “approximately 70 per cent of the ALPS treated water stored in tanks contains radionuclides other than tritium at the concentration that exceeds the regulatory standards applicable for discharge into the environment.”

Japan’s pledge that the waste water will be safely treated has won little sympathy in the islands’ region and neighbouring East Asian nations. TEPCO has an atrocious record of cost-cutting on safety issues and is facing financial ruin as it tries to decommission the damaged Fukushima reactors. By the end of last year, TEPCO had already spent 1,443 billion yen (US$13 billion dollars) to decommission the Fukushima No.1 reactor, but in coming decades, total costs for the removal of the melted nuclear fuel debris are estimated at 8 trillion yen!

Beyond this, there is also a long history of unilateral decisions by Japanese governments on nuclear waste dumping or the transport of plutonium MOX fuel, with repeated disregard of past pledges for consultation with island leaders.

In 1979, Japan planned to dump 10,000 drums of high level nuclear waste into the deep ocean Marianas Trench, in breach of the London Dumping Convention, an international treaty that entered into force in 1975 and prohibits ocean dumping of high level radioactive waste. After massive regional protests, then Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone pledged in 1985 that “Japan had no intention of dumping radioactive waste in the Pacific Ocean in disregard of the concern expressed by the communities of the region.”

Since then, a number of international treaties have created obligations for Japan to prevent significant transboundary harm in the Pacific, including the 1986 ‘Convention for the Protection of the Natural Resources and Environment of the South Pacific Region’ (the Noumea Convention) and the 1995 ‘Convention to Ban the Importation into Forum Island Countries of Hazardous and Radioactive Wastes and to Control the Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within the South Pacific Region’ (the Waigani Convention).

Time for dialogue

As the proposed waste dumping was announced on 13 April, then Forum Secretary General Dame Meg Taylor condemned the plan: “We are of the view that steps have not been sufficiently taken to address the potential harm to our Blue Pacific continent, including possible environmental, health, and economic impacts. Our fisheries and oceans resources are critical to our Pacific livelihoods and must be protected.”

Her newly elected successor Henry Puna has also reiterated this concern, seeking briefings from the Japanese government and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Speaking to journalists at his first press conference, Puna said: “Our concern is that we haven’t received enough information on this matter, and that’s all that we’re asking because of the legacy of nuclear waste that we’ve had as a region, in the Marshall Islands and Tahiti. This issue affects all of us and concerns all of us in the Pacific. That’s why we are engaged in a process with Japan to allow us to have access to all information, so our leaders can make an informed decision based on science and not on emotion.”

The Suga government was initially reluctant to allow Fukushima onto the agenda as it hosted the ninth triennial Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM9) on 3 July. Pacific officials pressed hard to challenge this censorship, and Secretary General Puna diplomatically noted: “Japan is a valued partner of the Forum and will always be.…While there have been some reservations not to have that item on the agenda of PALM9, it was in the spirit of this positive relationship that Japan has agreed that it will be on the agenda for discussion by leaders.”

Following the meeting, Forum chair Kausea Natano – the Prime Minister of Tuvalu – issued a statement welcoming the ongoing partnership with Japan: “Today we have the opportunity to advance our dialogue and cooperation in areas of critical concern to our Blue Pacific. COVID-19 response and recovery, climate change and disaster resilience, and the sustainable management of our oceans are foremost among these.”

He added, however, that “we seek honest and frank dialogue on Japan’s intention to discharge Advanced Liquid Processing System treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the Pacific Ocean. We want to ensure no harm to our Pacific Ocean, environment and our people.”

Addressing the dispute, the final PALM9 communique highlighted “the priority of ensuring international consultation, international law, and independent and verifiable scientific assessments. The Forum Leaders welcomed Japan’s intent of ensuring transparency and continuing close dialogue with Forum members.”

Despite this theatre of dialogue, Japan has only provided limited access to technical and scientific studies on the ALPS process. Forum member states are clearly expecting more detailed engagement on technical questions, given the perception of nuclear contamination, as well as any extensive spread of radioactive isotopes, will damage the Pacific fisheries industry. As Henry Puna notes: “Only the disclosure of information based on science will satisfy and appease the members.”

Nuclear Legacy Task Force

Even during the COVID pandemic and climate emergency, the issue of nuclear weapons and nuclear waste keeps forcing its way onto the regional agenda.

In December 2020, signatories to the 1985 Rarotonga Treaty for a South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone (SPNFZ) held their first ever meeting of states parties, more than 35 years after the treaty was signed. This initiative came as New Zealand and nine Forum Island Countries have signed and ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which entered into force in January.

The TPNW focuses on the abolition of nuclear weapons rather than arms control, creates obligations on signatories not to assist in the deployment of nuclear weapons and includes unprecedented obligations to provide assistance for survivors of nuclear testing and the environmental remediation of nuclear sites. It’s no surprise that nuclear weapons states are opposed to this treaty, but they are joined in their opposition by countries like Australia and Japan, whose defence forces and intelligence bases are integrated into US nuclear war fighting strategies.

For many years, the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) has pushed the nuclear issue onto the agenda of the Smaller Island States group and the annual Forum leaders meeting. Successive RMI presidents have highlighted the health and environmental legacies of 67 US nuclear tests at Bikini and Enewetak atolls and the leakage of radioactive isotopes into the marine environment from the Runit Dome (a massive concrete dome that houses dumped contaminated materials and radioactive waste on Runit island in Enewetak atoll).

In response, the Council of Regional Organisations of the Pacific (CROP) has established a Nuclear Legacy Task Force, involving representatives from the Pacific Islands Forum, University of South Pacific, the Pacific Community (SPC), South Pacific Regional Environment Program (SPREP) and other regional agencies.

At a time when Forum governments are focused on the climate emergency, the Blue Pacific oceans agenda and the health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s a challenge for this task force to maintain momentum.

The Nuclear Legacy Task Force is hampered by the lack of commitment from the governments of Australia and French Polynesia, which are reluctant to criticise the United States, France and Britain at a time these Western powers are ramping up strategic engagement in the Indo-Pacific region to contain Chinese influence in the islands.

Despite the 193 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls, French Polynesia is not on the agenda of the CROP working group. Paris rather than Papeete is responsible for defence and security policy, which constrains the Fritch government in Tahiti, even though French Polynesia joined the Forum as a full member in 2016.

In a similar vein, UK nuclear testing in Australia is not on the Task Force agenda, despite the radioactive legacies of British atomic tests at the Montebello Islands in 1952, as well as testing at Maralinga and Emu Field in the desert of South Australia, on the lands of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara and Maralinga Tjarutja peoples.

The regional work programme on nuclear issues has also been disrupted by the announcement by five Micronesian governments that they will withdraw from the Forum after their joint candidate for Secretary General, RMI’s Ambassador Gerald Zackios, was not elected to the position last February.

The RMI government is eager for regional support in its ongoing dialogue with Washington on nuclear clean-up and compensation and the CROP task force was initially led by Rhea Moss-Christian, chair of the RMI National Nuclear Commission. However last April, as Marshall Islands announced its withdrawal, the RMI Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote to the Forum Secretariat stating: “In light of the present circumstances and RMI’s intent to withdraw from the Pacific Islands Forum, I wish to advise that Ms. Moss-Christian will be stepping down from her role as chair of the task force. RMI will continue to join the task force discussions throughout the period of withdrawal, but will not serve in a leadership role.”

Despite all these constraints, Forum Secretary General Puna told Islands Business that “the nuclear issue fits very much into the oceans issue, which is a priority for us. Given that we have a legacy of nuclear testing and the probable leak of waste into the ocean from the Dome in the Marshall Islands, that is a real concern to the Pacific. On top of that, of course, is the Moruroa atoll testing. Thankfully, France has finally acknowledged that they are responsible for the fallout and the impacts on the people who were exposed to that nuclear fallout. So this is very much a central issue for the Pacific Islands Forum.”

With French President Emmanuel Macron scheduled to visit French Polynesia in late July, this “central issue” will not go away. Nuclear survivors and independence parties in Tahiti are planning a mass rally on 17 July, highlighting the ongoing failure of France and other Western powers to provide adequate compensation for nuclear survivors and undertake environmental remediation of nuclear sacrifice sites.

Japan’s diplomatic own goal

Beyond the Pacific Islands Forum, other countries have formally registered objections with Japan over the planned release of Fukushima waste water. Forum Secretary General Puna notes: “Our member states have some concerns but it’s also a concern that is shared by other neighbouring countries like China, Korea, the Philippines and even within Japan themselves, like the fishermen and environmental groups.”

Last month, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin stated: “Japan could have spent the two months in full consultation with stakeholders in the international community, adjusting the disposal of the wastewater, and rectifying the chaotic management of the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). However, the Japanese government has wilfully persisted in pushing forward the preparations for the discharge of the wastewater, and so far has failed to respond seriously and responsibly to the concerns of the international community.”

At present, the main focus of the Forum Secretariat in Suva is to promote dialogue with Japan and seek further technical and scientific information about the proposed dumping program, which will continue for 40 years. But the diplomatic tone is likely to sharpen as the Suga government moves closer to start ocean dumping in 2023. Across the islands region, church and community organisations have already condemned Japan’s plans, highlighting the importance of the ocean for livelihoods, culture and identity.

In a statement, the Pacific youth network Youngsolwara asked: “How can the Japanese government, who has experienced the same brutal experiences of nuclear weapons in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wish to further pollute our Pacific with nuclear waste? To us, this irresponsible act of transboundary harm is just the same as waging nuclear war on us as Pacific peoples and our islands.”

Ni-Vanuatu leader Motarilavoa Hilda Lini, a former director of the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre says: “We need to remind Japan and other nuclear states of our Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement slogan: if it is safe, dump it in Tokyo, test it in Paris and store it in Washington, but keep our Pacific nuclear-free. We are people of the ocean, we must stand up and protect it.”