A ship’s mast stands in the atrium of Porirua’s Pātaka + Art Museum.

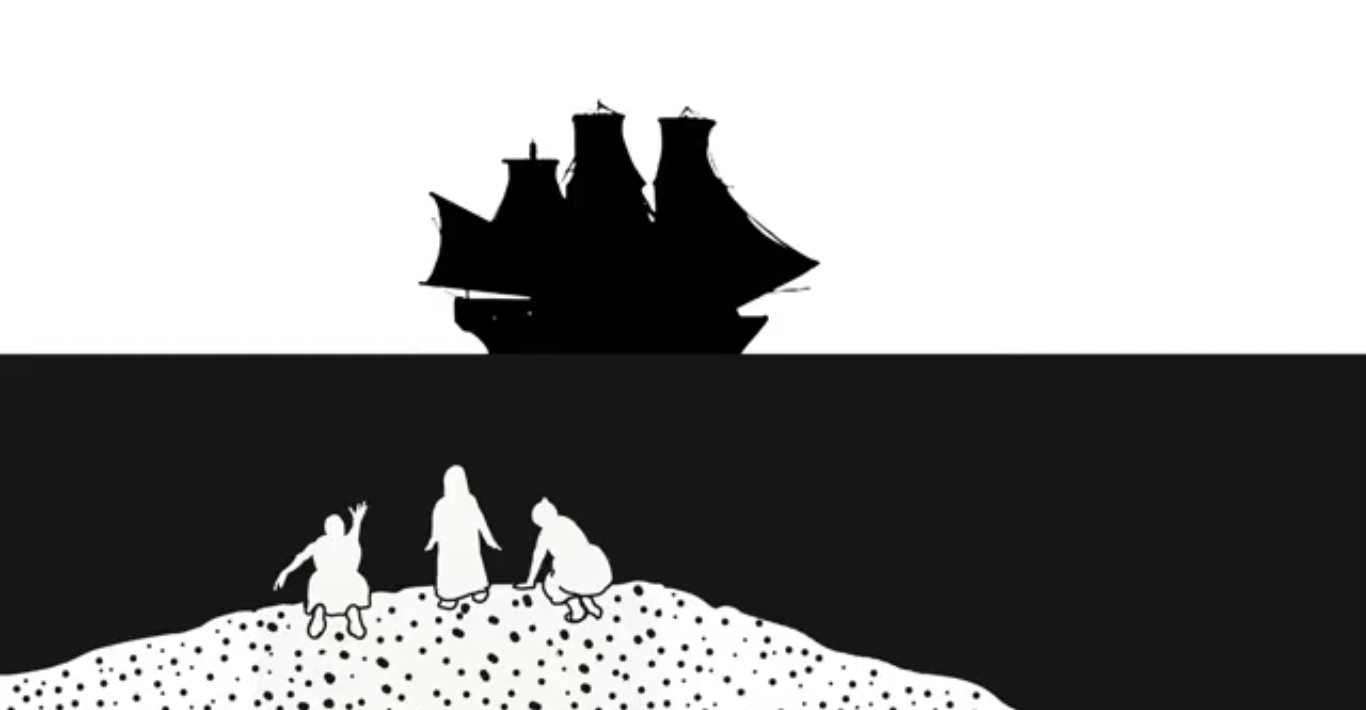

Projected on its three sails is a 12-minute audio-visual story of how Tokelauans were abducted into slavery, lured on board a Peruvian slave ship under the guise of trading goods. Playing in the background is Tagi Sina, a song by musical group Te Vaka which laments the devastation it caused.

The installation, Cry of the Stolen People, tells part of the little-known history of “blackbirding”, of how Peruvian slave ships kidnapped more than 250 Tokelauans – virtually half of the population – from their communities on the atolls of Fakaofo, Nukunonu and Atafu in the early 1860s. They were then transported to the Port of Callao near Peru’s capital, Lima.

The story was told through a Tokelauan perspective, said visual artist Moses Viliamu, who created the installation, alongside other Porirua-based Tokelau artists Jack Kirifi, Mathew Lepaio and the late Zac Mateo.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of indigenous people in the South Pacific, from the Solomon Islands, Niue to the Easter Islands, were coerced or kidnapped into slavery by European colonists to work in plantations in Australia, Central or South America.

Slavery was abolished in the 1860s, Viliamu said, but the slavers circumvented it by targeting smaller Pacific islands and avoiding places with larger populations such as Samoa, Tonga or Fiji.

None of those kidnapped from Tokelau ever returned. On Fakaofo, the atoll’s population dropped from 261 to just 84 after slavers reached its shores, leaving behind mostly women and children. Only six men from Atafu deemed too old, sick or less than useful were left behind.

Many died on the journey to South America from malnourishment under harsh labour conditions. When Peru banned the practice in 1863 and ordered repatriations, diseases ravaged the returning ships, and they only reached as far as Rapa Nui and Rapa Iti (Easter Island and Little Easter island), Nuku Hiva in French Polynesia, as well as Tongareva in the Cook Islands.

Surviving Tokelauans who ended up at Rapa Nui married local women and started new lives, but in Tokelau, with the men gone, cultural practices including tattoo patterns were lost.

Cry of the Stolen People was exhibited in Hawaii at FestPAC, the world’s largest celebration of indigenous Pacific Islanders, earlier this year. At Pātaka it sits alongside other works from FestPAC.

Viliamu, Kirifi and Mateo came up with the idea when they were at Whitireia Polytech. Lepaio joined them after Mateo died.

Their parents knew about the history of blackbirding, Kirifi said, but often it was too painful or traumatising to share.

“It’s one of those stories that you don’t really talk about unless you’re researching,” he said. “We sat around the table and thought this is a good story to bring us all together as artists.”

Apart from their parents’ stories, research for the installation also originated from Slavers in Paradise by British historian and anthropologist Henry Evans Maude.

Viliamu was “more than excited” to bring the installation to Porirua. Data from the latest census showed more than a quarter of New Zealand’s 9822 Tokelauan population live in the city.

“Because a lot of us are New Zealand-born, I think it’s important to share our stories and our histories so that we can strengthen our identity,” said Viliamu, who was born in the Porirua suburb of Cannons Creek.

But many people the artists spoke to had never heard of blackbirding, something that was “surprising” for Viliamu.

He hoped the installation would help gather more information about blackbirding in other parts of the South Pacific. “We wanted to gather more information from the other islands because they went to Niue, Kiribati, Tuvalu, the Cook Islands,” said Viliamu. “We wanted to hear if anybody had any information and stories from those islands.”