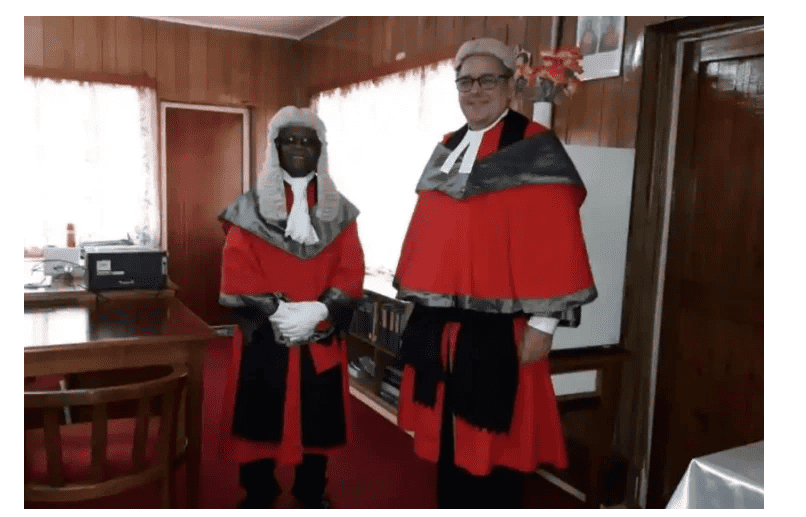

David Lambourne, an Australian-born high court judge whose attempted deportation two years ago from Kiribati sparked a judicial crisis in the Pacific nation, appeared in court in a case closely watched by the United Nations and international legal groups.

Lambourne, who has lived in Kiribati for 30 years and is married to opposition leader Tessie Lambourne, faces deportation if he loses a high court challenge to Kiribati president Taneti Maamau’s attempt to sack him. Kiribati will hold national elections later this year.

Lambourne has been living in Kiribati without a visa or salary since 2022 when Maamau suspended him, and then suspended all three court of appeal judges and the chief justice after they ruled Lambourne should not be deported.

One attempt at forced deportation amid legal proceedings in August 2022 failed when a Fiji Airlines pilot refused to accept Lambourne on the plane against his will.

Lambourne appeared in court on Tuesday.

“Today’s case involves the government’s continuing assault on the rule of law,” Lambourne’s barrister Perry Herzfeld told the court by video link from Sydney on Tuesday, pointing to what he said were issues of judicial independence.

Maamau had appointed a new tribunal to investigate Lambourne on an “extremely expedited timetable” with plans to hand a report to parliament next month, Herzfeld said. Lambourne’s legal team only learned days ago of the existence of the tribunal, he added.

None of the allegations made against Lambourne – including a disputed claim he took too long to make judgments – justified the president forming a tribunal to investigate his removal from office, he said.

It was also “fatal” under the constitution that the tribunal does not include a judicial officer, he added. Kiribati’s deputy solicitor-general Monoo Mweretaka argued in court the allegations against Lambourne were serious, and there was no requirement in the constitution for the tribunal to offer him procedural fairness.

There was also no definition of judicial office in the constitution, so it should not be restricted to legally trained officers, he added.

In a letter to Kiribati’s government in September 2023, Margaret Satterthwaite, UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, said she was “seriously alarmed” at the series of suspensions of judges, which left Kiribati without a functioning high court or court of appeal to act as a check on the power of parliament.

The letter also raised concerns that Lambourne’s treatment and the lack of a judicial officer on the tribunal could breach human rights standards.

An interim visa issued to Lambourne in January expires when a judgment is delivered by the court.

High court commissioner Aomoro Amten on Tuesday reserved his judgment.

Kiribati’s parliament sits for a final session next month, before dissolving in May ahead of national elections.