A deep-sea mining operation that recently took place off the coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) has raised alarm bells for environmentalists and called into question the validity of the country’s moratorium on such activities.

Between 16 May 1and 19 July, the mining vessel MV Coco ventured into the Bismarck Sea close to the west coast of PNG’s province of New Ireland. Environmentalists say the vessel was mining the seabed — an allegation confirmed through reporting by Pacific Beat, an Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio show. The vessel is owned by Magellan, a deep-water exploration and mapping company based in Jersey in the Channel Islands, and was chartered by Deep Sea Mining Finance (DSMF) Ltd., an obscure company registered in the British Virgin Islands but with a company address on the Isle of Man.

According to environmentalists, DSMF’s mining operation was illegal and went beyond the exploration phase permitted under its current license. However, a government official has denied the operation’s illegality, although he said the company’s activities caught his agency and the provincial government by surprise. The exact nature of the seabed mining and the conditions of the company’s license remain unknown.

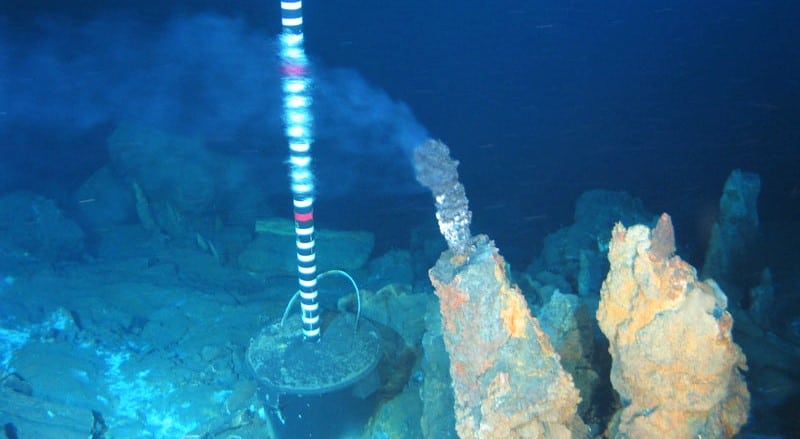

Satellite-based vessel-tracking data Mongabay obtained from monitoring platforms Skylight and Global Fishing Watch show the MV Coco focusing much of its activity in and around a controversial project site known as Solwara 1, which harbors hydrothermal vents with abundant minerals like copper, gold and other metals.

The Solwara 1 project site was originally allotted for mining by Canada-based Nautilus Minerals. But in 2019, amid strong local opposition to the project, the company went bankrupt and was delisted from the Toronto Stock Exchange, leaving the PNG government, a major investor in the project, with millions of dollars in debt. DSMF later acquired Nautilus and all of its assets, including three mining licenses. The most notable of these is the Solwara 1 license, which was approved in January 2011 for a period of 20 years. It is not clear whether the two other licenses have been approved. After a period of quiescence, the PNG government confirmed in August 2023 that the Solwara 1 project was again moving forward.

Vicky Amoko, senior litigation lawyer at the PNG-based Centre for Environmental Law and Community Rights (CELCOR), told Mongabay in an email that full details of the 2011 mining license document have never been publicly released, and the scant information available was only revealed through court proceedings initiated by community plaintiffs against state entities.

Helen Rosenbaum, the research coordinator for the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, an association of NGOs and individuals who advocate against deep-sea mining, said she had been informed that DSMF was operating under an exploration license, rather than an exploitation license. However, she acknowledged that she had not seen the license to know for sure. Mongabay was also unable to access the license.

Deep Sea Mining Campaign stated in an Aug. 13 press release that the MV Coco extracted about 180 metric tons of material from the west coast of PNG’s New Ireland province, based on information it obtained from sources familiar with the operation. Moreover, the group alleged the mining company had “stockpiled” even more material “without authorisation,” carrying out a type of mining that went beyond exploration.

“This was not merely an exploration exercise,” Rosenbaum told Mongabay in an email. “Nautilus had already conducted many of these. DSMF was trialing new equipment to mine the hydrothermal vents. Doing this over a 6-week period constitutes the first phase of mining.”

DSMF did not respond to Mongabay’s multiple requests for comment about the nature of the mining operation.

In the press release, Rosenbaum also stated that the operation was illegal because DSMF was conducting its work “without an environmental impact statement relevant to its method of mining, an environmental management plan, or emergency response plan.”

The PNG Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC), now known as the Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA), administers the legal framework that would oversee the environmental regulation of the Solwara 1 project. According to a 2011 report released by CELCOR, the NGO MiningWatch Canada and their partners, the former company Nautilus submitted an environmental impact statement (EIS) to DEC in 2008. This was eventually approved by the government — despite containing what the report authors described as “significant gaps.”

Since acquiring Nautilus, DSMF does not appear to have submitted a new EIS. Amoko of CELCOR said the company is also operating via an environmental permit that was approved for Nautilus back in 2009. She added that PNG does not actually have a legislative framework for deep-sea mining, which would lay out rules for such activities.

CEPA did not respond to Mongabay’s questions regarding this matter. Jerry Garry, managing director of PNG’s Mineral Resources Authority (MRA), and the office of James Marape, PNG’s prime minister, also did not respond to Mongabay’s inquiries.

In terms of the operation’s legality, Garry told Pacific Beat that DSMF’s recent sampling was part of a preexisting approved work program for mining exploration and that the operation was legal. However, he also noted that DSMF “failed to alert the MRA and the provincial government prior to their work,” and that the MRA became aware of the company’s actions only when DSMF sought permission to export samples for testing.

Critics have also pointed out that DSMF’s operation went forward despite two moratoria being in place, which should have prevented any kind of deep-sea mining from occurring in PNG’s waters.

In 2019, Prime Minister Marape announced a 10-year moratorium on deep-sea mining at a meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum, an intergovernmental organisation that aims to foster mutual support among 18 countries and territories in the Pacific. Then, in August 2023, the Melanesian Spearhead Group, which includes Fiji, PNG, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, announced another moratorium on deep-sea mining within member states’ territorial waters.

However, Garry told Pacific Beat that PNG’s mining minister (who works within the MRA) had not advised him on any moratorium.

Dozens of nations have called for a moratorium or a “precautionary pause” on deep-sea mining in international waters. Critics argue that deep-sea mining could cause irreversible harm to the seabed and surrounding marine environment with sediment plumes and other forms of pollution. A recent study in Nature also suggested that polymetallic nodules — a primary target for many mining companies due to their mineral-rich composition — produce a form of “dark oxygen,” which has led many decision-makers to call for further research and for slowing or even halting the rush to mine the deep sea.

On the other hand, advocates of deep-sea mining say there’s no time to waste in getting started with mining the seabed, citing the difficulties of obtaining many of these minerals. There is an oft-repeated argument that deep-sea minerals, such as cobalt, copper and nickel, are needed for electric car batteries and other renewable energy technologies. Representatives of Canada-based deep-sea firm The Metals Company (TMC), which is looking to begin deep-sea mining in international waters in the near future, also argue that deep-sea minerals are needed for national security purposes in the U.S., particularly since China currently has a monopoly on rare earth metals and other critical minerals.

In 2022, TMC also utilised the MV Coco to monitor the impacts of their test mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a region of the Pacific Ocean beyond national jurisdiction where polymetallic nodules abound. This test mining operation was also steeped in controversy — in this case, due to the alleged covertness with which the International Seabed Authority, the UN-affiliated deep-sea mining regulator, approved the operation without consulting its council members. The environmental NGO Greenpeace also published a video purporting to show the Hidden Gem, the vessel conducting the test mining, discharging polluted water back in the sea — a finding that TMC refuted.

Although a few such exploratory deep-sea mining operations have taken place, full-scale, commercial seabed mining exploitation has not started anywhere in the world.

John Momori, a member of the Alliance of Solwara Warriors, an association of community members based in PNG near the Bismarck and Solomon seas, many of whom have been campaigning against deep-sea mining in PNG for more than a decade, and an officer of the Catholic Diocese of Kavieng, which includes New Ireland, has raised concerns about DSMF’s operation. He made reference to the health of the ocean following the test mining.

While it is still unclear whether the seabed was damaged during DSMF’s test mining operation, Momori noted that the sea along the west coast of New Ireland has been changing color, making it difficult for local people to fish and dive. Coastal communities in the area, which has a high poverty rate and lacks grid electricity and many other government services, depend heavily on the sea for survival.

“The people of West Coast Namatanai, especially from Ward 3 to Ward 6, are now experiencing the changes in the colour of the sea,” Momori said in a statement. “What once used to be a mix of turquoise to a deep set dark blue color has now become murky.”

Jonathan Mesulam, a spokesperson for the Alliance of Solwara Warriors, said it was “very frustrating” to learn that DSMF had returned to PNG to conduct its testing and sampling.

“It makes us really angry,” Mesulam told Mongabay over the phone. “We felt that the government had lied to the people by supporting the moratorium,” he said.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of this publication.