Geopolitical competition can have adverse impact on third-party countries. We are seeing this in Solomon Islands, where domestic political discourses – at least in Honiara and on social media – are dominated by the country’s relationships with China and the US and its allies. These are characterised by divergent opinions that have caused divisions that could have long-term negative effects on Solomon Islands.

On one side are those who perceive China (and its flotilla of state officials, companies, citizens and investors) as a saviour of Solomon Islands, and its intentions as purely benevolent and infallible. They highlight the role of the Chinese state and Chinese companies in infrastructure developments, such as the newly built national stadium, Munda airport terminal, Solomon Islands National University’s Panatina office and classroom complex, and the Mongga Bridge in East Central Guadalcanal. But they often do not mention that while most of these projects were built by Chinese contractors, they were financed by other funding agencies such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the Solomon Islands government. The China proponents decry the US and its allies, and ignore Australia’s 13-year and $2.6 billion investment in RAMSI (Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands), or dismiss it as largely beneficial to Australia through “boomerang aid”. They present themselves as defenders of China in Solomon Islands.

On the other side of the debate are those who dislike China because they see it as a one-party communist dictatorship. They highlight its suppression of minorities such as Uyghurs, and the corruptive influence of Chinese entrepreneurs, and they accuse Beijing of being anti-Christian. They contrast this to the US and other Western countries that they consider as hallmarks of liberal democracy, which Solomon Islands should emulate. They present China as a monolithic entity with total control by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This is despite the complex web of Chinese actors with sometimes differing interests, and the fact that the CCP might not necessarily have control over all of them. This group is generally uncritical of Western countries’ colonial histories, including the US, Great Britain and France’s nuclear weapons testing in the region. They are vehemently anti-China and wear it as a badge of honour.

These groups with differing opinions “shout” at each other, mostly on social media. This has caused divisions, for example between the national government and the Daniel Suidani-led Malaita provincial government. Such divisions are socially corrosive and could degenerate into violence, as seen in the November 2021 riots in Honiara.

However, there is a middle ground for constructive conversation. This should emphasise how the Solomon Islands government could manage its engagements with competing global powers in ways that would ensure the interests of Solomon Islands are privileged, rather than it being a pawn in global power projections.

Solomon Islands needs China, the US, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and other development partners. Fundamental to these partnerships should be the improvement of Solomon Islanders’ livelihoods, by providing access to adequate and quality social services such as health, education and transportation. Solomon Islands must dictate and manage the agendas of its international relations. These are development partners – not saviours towards whom Solomon Islands should be subservient.

China is Solomon Islands’ largest trading partner. Most exports to China are round logs and other primary commodities with little value added. This is unlikely to change soon, given the nature of the country’s economy and the dominance of the export and import sectors by Chinese entrepreneurs and companies. Solomon Islanders have been largely restricted to resource rent recipients. The economy therefore generates tax revenue for the state, and some jobs, but leaves most Solomon Islanders at the margins of the country’s economy.

Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, Japan and other donor partners are equally vital in assisting Solomon Islands in the provision of social services and improving its productive sectors, especially those that directly involve Solomon Islanders. This could include value-added industries and access to high-value niche markets that might not be visibly tantalising like a stadium, but could potentially be more impactful in the long term.

The US is in a bit of a quagmire. Its increasing engagement with Solomon Islands is reactionary, an attempt to counter China’s growing influence. But it can’t act fast enough, and risks overpromising and underdelivering. Unlike Beijing where there is centralised decision-making, Washington has to go through congressional processes. That is challenging, especially given the current divisions in US domestic politics.

Despite this, Solomon Islands must capitalise on its renewed interest and push Washington to deliver on its promises, particularly those outlined in the Declaration on US-Pacific Partnership. Recently, the bipartisan Congressional Pacific Islands Caucus reintroduced the Boosting Long-term US Engagement in the Pacific (BLUE Pacific) Act. This piece of legislation was first introduced in July 2020 and lays out a renewed vision and framework for US foreign policy in the Pacific Islands over the coming generation. Honiara should not turn a cold shoulder on Washington. Rather, it should maximise the renewed interest to the benefit of Solomon Islanders.

It is not easy for a small island country to manage global powers that could easily exploit its vulnerabilities, by tickling the egos of its leaders, persuading them to accept development projects that are visually seductive, but benefit a few and leave long-term costs that the country can’t afford.

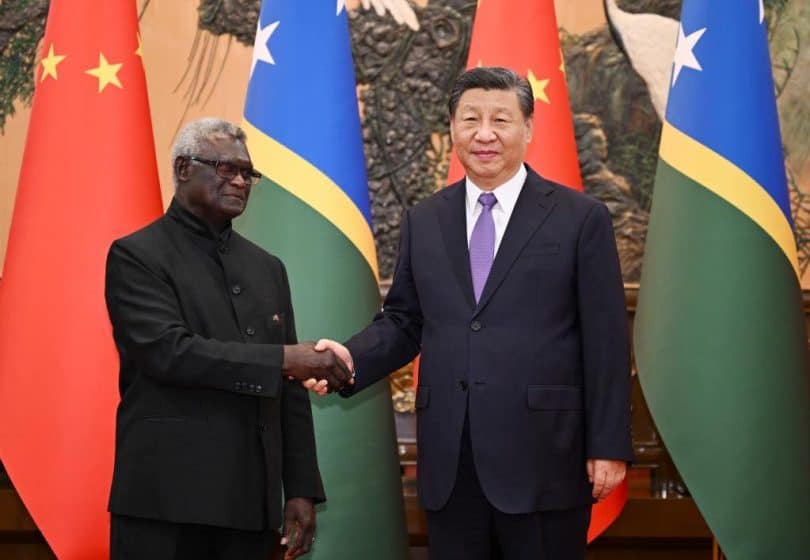

“Visit diplomacy” has often been used to seduce leaders, by playing on their ego and sense of self-importance. Since 2019 there has been a fleet of high-level officials from China, the US, Australia, Japan and others visiting Honiara. Large Solomon Islands delegations have visited other countries. Beijing is a master of visit diplomacy. The Chinese government has rolled out the red carpet, mounted guards of honour and pampered Solomon Islands politicians. In a visit to Beijing in early July 2023, Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare was caught on video saying “I am back home” to Chinese officials on his arrival in Beijing. Other countries are likely to entice Solomon Islands with such visits, but they are unlikely to outmatch Beijing.

In this era of increasing geopolitical competition, Solomon Islands must not kowtow and become a tributary state of others, including China and the US. All development partners are important. But most fundamental is the wellbeing of Solomon Islanders. It is therefore important that Solomon Islanders find a middle ground to discuss their country’s relationship with global powers.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Tarcisius Kabutaulaka is an associate professor and former director of the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He is from Solomon Islands.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of this publication.