‘Three scores and ten’ is the age allotted to humans, the Good Book tells us. Modern medicine might add 10 odd years, but the end is in sight, the shadow lengthening visibly.

By that measure, my time is up or will soon be. I am a late Second World War Fijian, now marching lock, stock, and barrel into niggling dotage. Ours has been an improbable journey. ‘One step at a time’ could have been the motto of our generation.

Our children find the time and place that formed (and deformed) us challenging. Our grandchildren think I am positively hallucinating when I tell them that I was born in my parents’ house on a farm, like most village children of the time, that I grew up without electricity, running water or paved roads, that we walked barefoot to school after completing our daily allotted household chores.

No television, no internet, no iPads, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, and God knows what else. ‘But, Grandpa, what did you do?’ A good question.

Despite the limitations of time and technology, we not only survived but triumphed. We may have started with nothing, but we achieved much and went places beyond the imaginative grasp of the folks before us. We like to think that we were the original lucky generation of Fijians.

The world was opening when we arrived on the scene. Radio was connecting us to the world and to ourselves, Pan Amwas landing at Nadi International Airport and ocean liners, Oran say and Oriana, were bringing large numbers of tourists to the islands in search of romance and adventure. We never imagined we would one day become tourists in their lands.

Primary school was put on a firmer footing. All school-age children were expected to complete at least some portion of schooling, mastering elementary arithmetic and English to decipher dockets or write letters. Secondary schools were no longer the rarity they had once been. Labasa Secondary, as it then was, opened its doors in 1954 and other schools followed. In Viti Levu, Shri Vivekananda High (SVH) became the first non-government, non-Christian secondary school to start in 1949 courtesy of Ramakrishna Mission whose motto was: Satya Men Vijayete. The Truth shall set you free.

Then came the University of the South Pacific in 1968 just as we were completing high school. The founding of that institution marked a turning point in the history of Fiji and the broader Pacific region. Until then, only a small number of students on government or their parent’s scholarship went abroad for tertiary education. After USP, tertiary education became available to bright students from poor families. To USP, our generation owes more than it is possible to express in words.

Many hurdles had to be crossed before we could enter the portals of that institution. There was an external exam at each step of the way. First there was the Entrance Exam which determined whether we could qualify for a place in a secondary school. At high school, we did Fiji Junior Exam, NZ School Certificate and finally NZ University Entrance. A few years before us, students sat for Junior and Senior Cambridge empire-wide exams.

Failure in any of these usually meant the end of schooling and all that it represented. We had no sense of entitlement and often no second chances either. That we passed at all was a miracle given what we had to wade through in our classes. Our primary cohort began with The Caribbean Readers after which we moved on to Oxford African Series, before finally landing on University of London’s ‘Reading for Meaning. Ami Chandra’s Hindi Pothis introduced us to the cultural heritage of India, which we shared with our unlettered parents to their great delight.

High school history students, as Mr Krishna Datt will attest, studied such weighty topics as the Causes of World War One, the Russian Revolution, the Unification of Germany and Italy and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. And in literature, Vijay Mishra and Subramani, now both professors of English Literature, introduced us to the pleasures of the imagination through the novels, poems and plays of Shakespeare, TS Eliot, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Dickens, the Bronte sisters, Joseph Conrad, and John Steinbeck. Their words still roam around in my mind.

Thoroughly Eurocentric texts and the curriculum, you might say, and now pilloried by postcolonial critics. But I do not disparage this ‘colonial’ education. The books we read opened new horizons to us, connected us to distant pasts and places. They enlarged our sense of who we were, our common humanity. None of us ever considered Shakespeare as a ‘colonial’ or ‘Eurocentric’ writer. That thought is mildly repugnant to me. He taught us so much about the vagaries of the human condition.

I have met old timers, now probably gone, who could recite lines from Julius Caesar’: ‘Friends, Romans, Countrymen,’ from James Joyce’s Ulysses ‘Tho’ much is taken, much abides,’ and Samuel Taylor Coleridge Rime of the Ancient Mariner: ‘Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink’. I found their memories of their youthful reading deeply moving. In recent decades, much local content has entered the school curriculum, which is as it should be, but I hope the baby will not be thrown out with the bathwater.

Teachers were for us figures of great authority, exemplars of correct conduct, always respectfully addressed formally. They took their profession seriously rather than as a stepping stone for a career elsewhere in the civil service. They pushed us hard. Some of their examples has influenced my own teaching career, the capstone of which was the award of an ANU ‘Top Supervisor Award.’ And teaching has remained the cornerstone of my only career spanning four decades.

One deeply regrettable aspect of education during our time was its effective ethnic segregation. Fijian boys went straight from their provincial schools to Queen Victoria School or Ratu Kadavulevu School, and iTaukei girls to Adi Cakobau School in Sawani. Most Indo-Fijian pupils went to schools which were predominantly Indian, including even the government-sponsored Labasa Secondary. Marist was an exception, but not everyone could afford to go there.

We grew up with scant knowledge of the ethos and values of our neighbours. The barriers were breached much later. It is no wonder that Fiji has faltered so much in its postcolonial journey. I certainly hope that racially segregated education in Fiji is now firmly in Fiji’s past.

The University of the South Pacific was a real eyeopener for us. It was on the Laucala campus that we met and mingled with students from other ethnic groups for the first time and from different parts of Fiji and from wider South Pacific region. That broadening experience has remained with me. The regional character of the university is its greatest strength; its loss would be grievous.

It was at the Laucala campus that we discovered works about ourselves: books by Ken Gillion, Adrian Mayer, Cyril Belshaw, Ray Watters, EK Fisk and Oskar Spate, and poems, plays and short stories by us: Raymond Pillay, Vanessa Griffin, Pio Manoa, Jo Nacola, Subramani. We talked about such weighty topics as the meaning of independence and development for our country and punctured pomposity of our hierarchs without fear of retribution.

It was Imran Ali, I think, who published an article in ‘UNISPAC’ about the Fijian Senate which he titled A High Sounding Nothing, after the Congress of Vienna. Such freedom and innocence then.

We may have been blinded by our idealism and our dreams for a free and fair society, but the coup of 1987 came as a deep shock to us, to see armed soldiers turn on their own innocent civilians. That was something we associated with developing countries in Africa and Latin America. Disillusioned, many left Fiji altogether, taking with them skills and talent the country could ill-afford to lose. The haemorrhage continues unabated as Fiji’s best and brightest seek their future in foreign lands. This, too, is something people of my generation had never contemplated.

For a brief moment in the mid-1990s, a ‘Niu Wave Collective’ of writers and artists began once again to write about their personal and collective traumas, but subsequent ruptures put paid to that.

It is to the great credit to those who have chosen to remain in Fiji that they have kept the flickering flame alive.

I am sometimes accused of being an ‘elitist.’ I cannot, in good conscience deny that charge though I completely repudiate the thought that only elites should govern society. I am genuinely grieved by very bright people who could and should have done much better but have not. I have supervised several doctoral dissertations by students from Fiji and I know from direct experience how good they are. It is my hope that the coup culture of the last three decades in Fiji will not permanently corrode the spirit of critical enquiry.

I agree that I am a person of the past both by training as well as by temperament. I have vicariously witnessed the struggle of so many over so many decades to create a fair and just society in Fiji with the consent of the citizens. Failures—and there were failures along the way—did not daunt or deter them. They were always ready the next day to continue fighting for the values and ideals they held close to their hearts. The verdict of the ballot box might have been disappointing, but it was sacred. Rules were made to be observed. not breached at gunpoint.

Fiji was a country of cacophonous voices, sometimes discordant even, but that was a condition for a vibrant democratic society. The Parliament was not a bull pit for belligerent politicians with insufferable egos and overweening ambition. The Parliament was the people’s house to discuss matters with dignity and decorum (and, yes, a bit of pungent humour, too).

That is the past of which I was a part, mostly as a bystander and occasionally as a minor participant. That past for me cannot be erased just because it is inconvenient to the present. As I look back, I ask, with TS Eliot,

Where is the life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

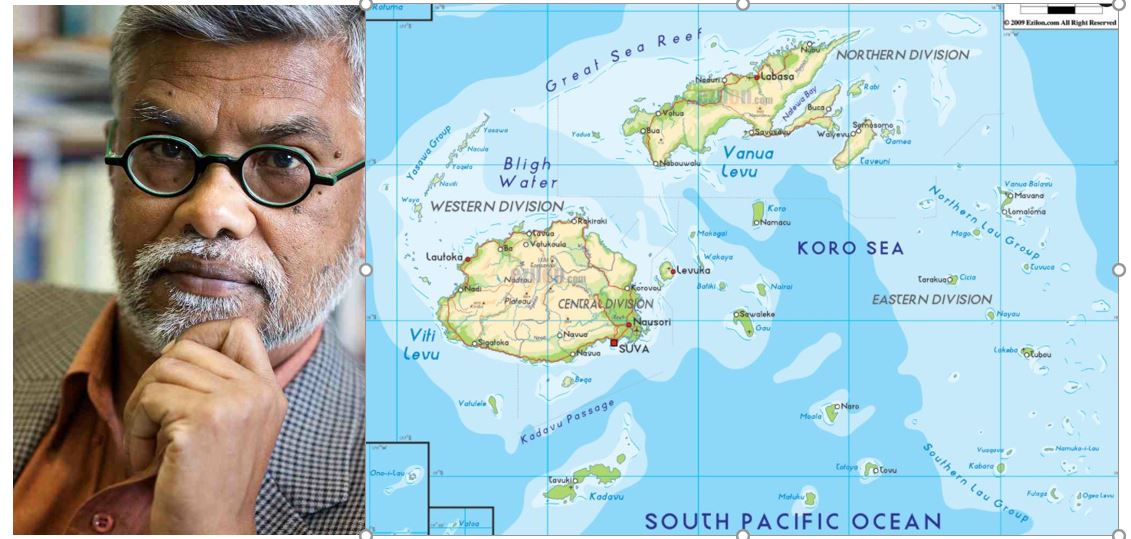

Tabia-born Professor Brij Lal’s books include Road from Mr Tulsi’s Store (2019). He and his wife Padma have been banned from Fiji for life by the Bainimarama government. They now live in Brisbane, Australia.