In the recent Parliament opening, King’s Representative Sir Tom Masters spoke of the Cook Islands’ desire to develop a sustainable and environmentally responsible seabed minerals sector. This week, also in Parliament, Leader of the Opposition Tina Browne criticised Government for rushing ahead in regards to deep sea mining.

Tina Browne said the Opposition was maintaining a very cautious approach to any commercial seabed mining activity given there are too many unknowns about the seabed and the long-term impacts of mining it.

This article draws on information from an article by the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, and seeks to inform on some of the potential impacts.

While it also includes references to mining seamounts and hydrothermal vents, the mining most likely to occur in the Cook Islands, and internationally in the Clarion Clipperton Zones, is for polymetallic nodules on the abyssal plains.

There is widespread concern about the impacts deep-sea mining will have on the ecosystems and habitats of the deep. Rules and regulations to safeguard the environment are still being worked out at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), of which the Cook Islands is a member. Alongside this, there are questions being asked about whether deep-sea mining is necessary or desirable, and whether it is economically viable.

Environmental impacts

Deep-sea mining is still in the experimental stage, and the impacts on deep-sea ecosystems remain unknown. But existing information has led scientists to warn that biodiversity loss will be inevitable – and most likely irreversible.

On the abyssal plains 4000 – 6000 metres deep, sucking up nodules would involve destruction of the seabed leading to the potential extinction of species. The nodules themselves support complex ecosystems, which would be lost. Each mining operation could effectively strip mine 8000-9000 square kilometres of deep ocean seabed over a 30-year mining licence period.

Stripping seamounts of the outer layer of ‘crusts’ containing cobalt and other metals would destroy deep-sea sponge and coral ecosystems that are likely to have taken thousands of years to grow.

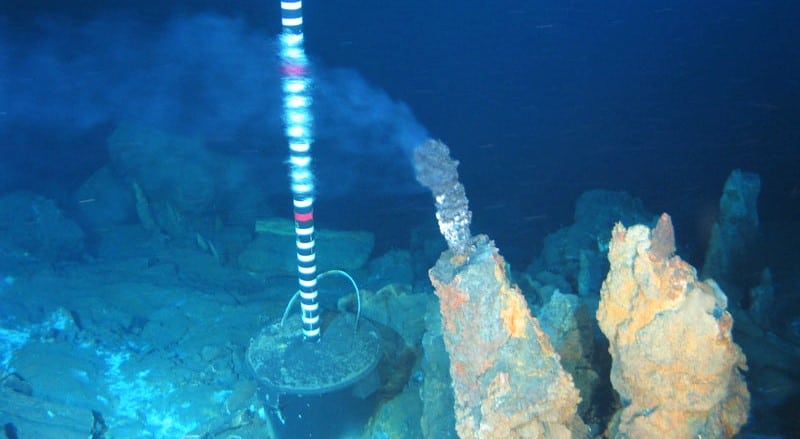

Mining of hydrothermal vents at much shallower depths of around 1600m would destroy vent habitats and kill the associated organisms before the biodiversity of these unique and fragile ecosystems is well understood. The Solwara 1 Project in PNG, for mining hydrothermal vents, was approved with an Environmental Permit for Development in 2009. However, the mining company went bankrupt and the PNG Government lost around US$200 million.

As well as the direct and immediate impacts of the mining operation on areas of the deep-sea actually mined, there are likely to be wider ecosystem effects on the marine environment. For polymetallic nodule mining proposed in Cook Islands waters, we have to consider plumes of sediment that will be created as mining stirs up the seafloor. These could possibly spread over tens of thousands of square kilometres, well beyond the mining sites. The effect this will have on filter feeders such as corals and sponges is still unknown.

Wastewater containing sediment and mine tailing, which may be toxic, pumped back into the ocean would also form plumes. These may travel hundreds of kilometres or further making their way into fish stocks and causing water cloudiness, impacting species that use bioluminescence to hunt or find mates.

Noise, light pollution and sediment plumes could also seriously impact species, such as whales, that use noise, echolocation or bioluminescence to communicate, find prey and escape predators.

Growing global opposition

Deep-sea mining is expensive, and though it may be profitable to individual companies, questions have been raised about its wider economic benefits when considered against the long term environmental risks.

A growing number of governments are now concerned about the environmental implications of deep-sea mining. Palau, Fiji, Federated Stated of Micronesia, Samoa, Vanuatu, French Polynesia, Germany, Costa Rica, Chile, Spain, Panama, Ecuador, Dominican Republic, New Zealand and the European Parliament have all called for a moratorium or precautionary pause. France has called for a ban.

Nauru, on the other hand, has stated its intention to force the ISA to allow The Metals Company to start commercial deep seabed mining in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (International Waters) as early as next year. This is despite the fact that the ISA has not yet agreed on environmental regulations to safeguard the environment in the face of mining. If the Cook Islands Government is sincere in wishing to make sure deep sea mining is done with the least impact on the environment, Te Ipukarea Society would encourage them to speak out against Nauru’s plans at the next International Seabed Authority meeting.