Having only limited access to food, money, shelter, and every means for a safe, comfortable life is a reality that Katia Cakacaka lived with for most of her life. Katia, who was raised on Matuku, one of Fiji’s very remote islands, shared that her family struggled a lot “since there were six of us needing school”. “Black tea and cassava were a normal menu item. Whatever money mum received, she made sure that we had flour, sugar, rice, and oil in the cupboard. For the rest of the food to go with it, she went fishing or got vegetables from the plantation,” she recalled.

Poverty hit harder when she and her family decided to relocate to the capital city of Suva, as her parents “thought that putting us in a boarding school would be best”. “I saw how much they were struggling to put us into boarding school so when it was my turn to continue my studies in Suva, I opted to stay with a relative in Vatuwaqa [a neighhourhood near Suva] so that it could ease their burden,” she said. “Going through this experience was a big challenge as I tried to navigate my way through. I had to walk most of the time back home from school, since I was not given enough cash, and I would be fed nicely only if mum and dad sent food rations on time,” she added. Katia, a survivor of breast cancer and gender-based violence, says despite facing adversity, it was support from her family and her faith in God that kept her.

Penina Tusoya, a single mother, has faced similar challenges: “Moving through so many work fields was one of the many challenges of my life as I tried to find a secure job to support my children.” She says joining a well-known regional organisation and earning only $20 FJD a day was just not enough. “It is very unfair to women when overseas staff make so much money. They paid me as a ‘volunteer’ even though I have qualifications,” she said. “A time came when I was only given $30 FJD a week for my transport to and from work after my formal contract had expired. So, my children and I walked miles to my workplace for months, and I saved whatever I could for my children to eat and pay bills, at the end of the week,” she added.

Penina is now looking after a community centre and garden, focusing on women-led agroecology and other projects at the Diverse Voices and Action for Equality (DIVA), a grassroots feminist collective based in Nadi, Fiji. “They (DIVA) offered me work and gave me all kinds of care, support, and feminist training. I have been through so much lately, some that I thought would break me… Now, I earn a living wage, and I am in a safe and caring workplace,” she said.

In February, DIVA released a new report, ‘Gender, Poverty and Economic Justice in Fiji: Grassroots-led Feminist and Human Rights Analysis’, which revealed that for female poverty, Oceania has the second highest rate (34.3%) after Sub-Saharan Africa (41.2%). The report highlights 23 sensitively described brave and often harrowing life-stories and analysis of the DIVA Poverty to Power Network, of which Katia and Penina are members. “Poverty is very much present in the Pacific region, whether we choose to recognise it or not. It is a major gender and development justice issue in Pacific small island states and societies,” the report stated. “It is a gross unfairness and distortion that Fijian state and society do not recognise in policy or in practice the huge burden of unpaid care, domestic and communal work carried by the women, girls, and gender diverse people,” it continued.

According to the Fiji Country Gender Assessment, unpaid work is highest among young mothers, single mothers, widows, women with disabilities, and women who have married into a community with more risk of social isolation and lack of kinship or local status. “Poverty in Fiji is not just about lack of decent work. It is that work in Fiji is a hybrid of communalism and individualist neoliberal capitalist systems. Women are captured in oppressive familial and community relationships, to provide endless work while being subjected to heightened conditions of poverty. This, while the State and society choose not to see, nor to respond, to the consequences,” the report stated.

The articulation of national, regional, and global development strategies and measures to address poverty and economic injustice generally do not address patriarchy and misogyny, it stressed. “The feminisation of poverty and gender injustice deepens as legislation, policy and practice do not serve women, children nor gender diverse people but rather an imagined male led, nuclear family-oriented system that is colonial, patriarchal and does not serve us in this complex time of polycrises, climate emergency, and ecological unrest,” it added. DIVA is aiming to address these issues at the 68th Commission on the Status of Women (CSW68) in New York on the 11th to the 22nd of March this year.

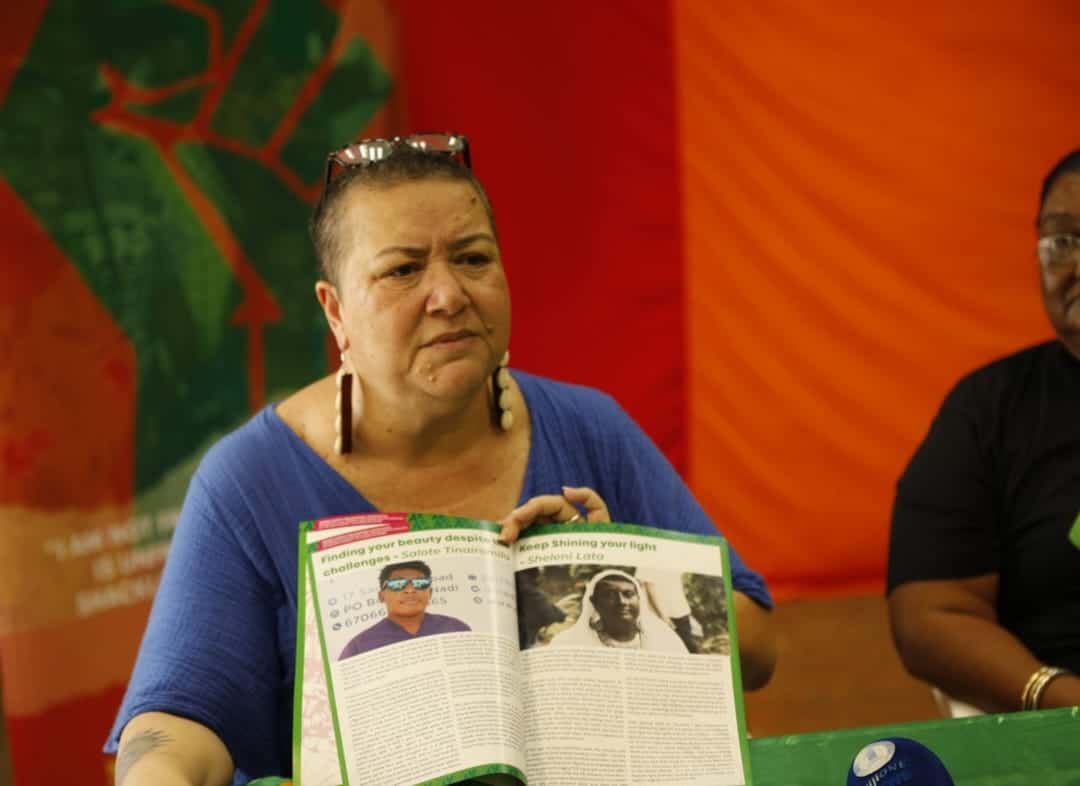

Executive Director of DIVA, Noelene Nabulivou, at the launching of the report, said: “We’re saying to each other, as women and as people, that in order to make things really about no one [being] left behind, we have to look behind us and also say, am I part of the problem? Am I not providing support to women and girls in my own area of work? Am I maybe leaving out people who really need urgent and lifelong support to change the systems? “The government already says that there are issues to do with water and sanitation, to do with housing, to do with adequate issues around gender-based violence and violence against children. What we need to do now is to work out what we are going to do about it,” she said.

“When we go to CSW68, we’re not just interested in what’s the language in the UN. We’re interested in feminists who are working on it at a ground level. What is it that we bring that maybe other groups don’t bring? They bring their own analysis, but we bring our knowledge from the streets and from the communities. “You should not just be talking up in the air. You should be listening to those of us who are doing the work on the ground. So that’s our right, …that makes sense in the work that we do,” she added.

Savena Devi, a member of DIVA’s Poverty to Power Network, reiterated: “We really need to know what our community needs and we should not work in silos.” As a grassroots woman leader, Savena has helped numerous women in Rakiraki, a small town on the north-eastern end of Viti Levu, engaging them in “local community activities to make use of the resources around”. “Gardening, farming – poultry, vegetables, crop and fruits, include people in organic awareness campaigns, form groups or clubs to help community members, and all these can change things to some extent,” she said.

“If I can change, others can change.” Savena believes to overcome poverty, change is necessary. “Many of us can live through poverty but we can be transformed to having power in ourselves. I think we need to start from childhood, not when we’re older. We can teach our children financial literacy and savings and teach them to budget – we use a part of their school spending and save the rest. Help them make this a habit and understand the importance of money and saving.”