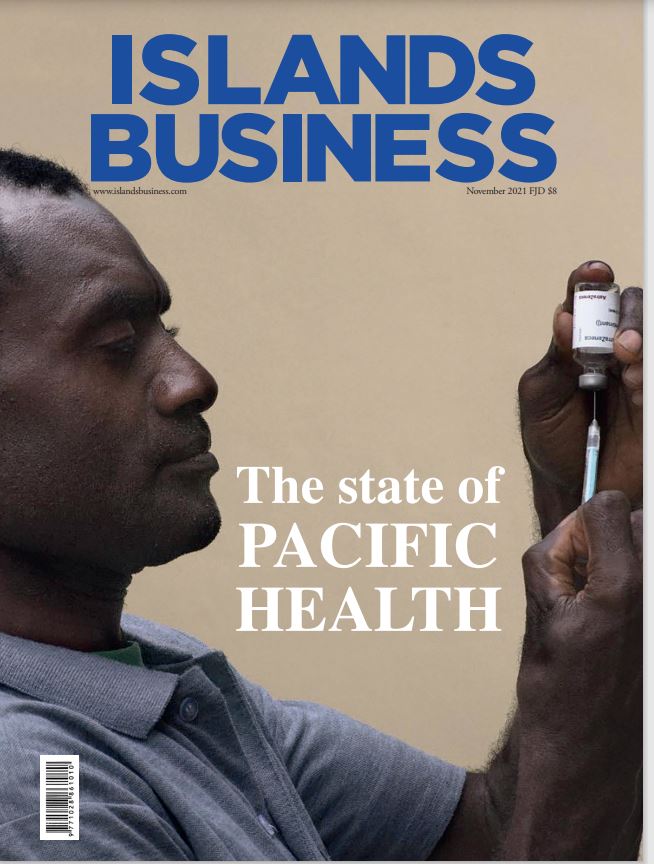

Pacific islands health care faces the crisis of a lifetime

The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t just highlighted the Pacific’s fragile health systems. It’s amplified the central role that public health plays in all aspects of our personal and public lives; from education to culture, travel to trade.

Pacific health leaders have been prompted to question our level of investment in health systems, how it’s been spent in the past, and what needs to be built for the future.

Health spending as a % of GDP (2019 . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...