Apisai Tora, a scion of the old guard of Fiji’s politicians, who dominated Fiji’s political stage for almost five decades, passed away on August 6.

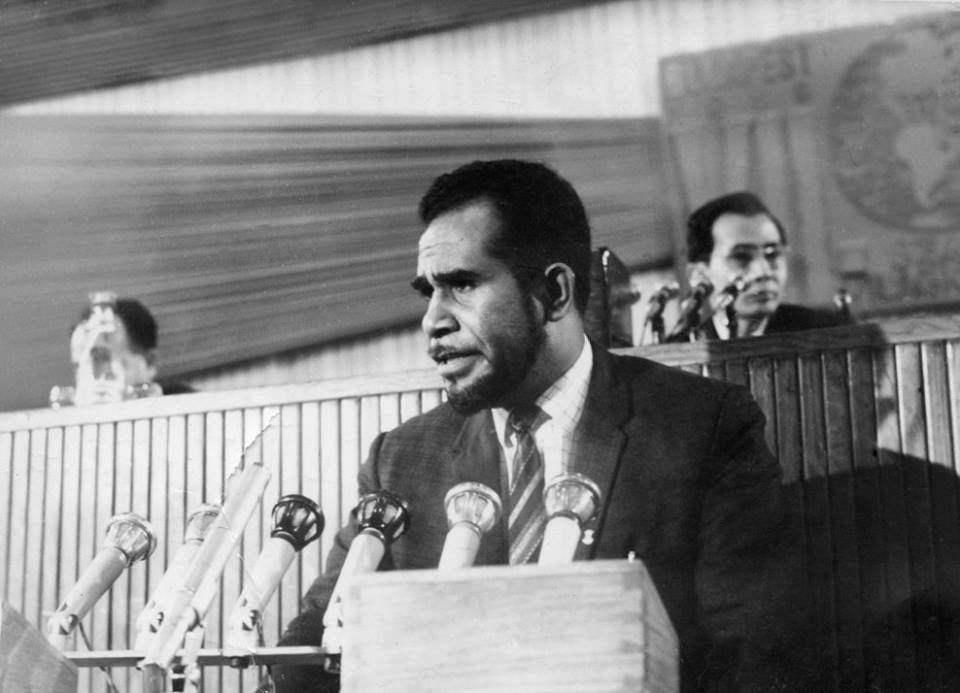

Variously described as a political maverick, a chameleon and a nationalist, Apisai Vuniyayawa Tora first entered the public domain in 1959 as a 25-year-old veteran of the Malayan campaign.

Together with fellow unionists, they organised the oil strikes of 1959 which led to widespread rioting under British rule. To some observers, this period in Fiji’s history symbolised a kind of Fijian Spring and the nascent stirrings of Fijian political consciousness.

Around the world, other political movements and voices were also rising to assert their rights and challenge European colonial and corporate domination.

In Algeria, the war for independence continued to rage. In Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser triggered a crisis when he announced plans to nationalise the Suez Canal. And in racially segregated America, Martin Luther King was about to take up the leadership mantle for the Civil Rights movement.

Traditionally from Sabeto in Fiji’s west, Tora admired the way Egypt’s Nasser wrested the Suez Canal from British/French corporate hands, prompting him to pen a letter to Time Magazine. In it, he described Fiji as “a white man’s paradise and a black man’s hell”.

Not expecting it to get published, he was delightfully surprised when it was.

The letter, however, underscored the anger brewing within, over the inherent injustices in the class and racial divide. It was a divide that rewarded those born into privilege and emasculated those with the misfortune to be born poor, black or both.

In the early years of Tora’s public life, it was this anger that fuelled and drove him into fearless action, often triggering incidents that landed him in trouble. He didn’t think too kindly of a number of prominent chiefs, believing they lacked intellectual leadership and questioned what he perceived to be their lack of accountability to the iTaukei.

Similar views were held of some of the white colonial masters.

There is a well-known story of a time in the 1950s, when he was working for the District Officer [DO] in Ba in Fiji’s West, and serving behind a counter. In front, was a long queue of people patiently waiting to have their documents processed. In the middle of this scene, a senior white official from the Colonial Sugar Refining Company walked into the room, bypassed the queue, pushed his way through to the front counter and demanded to be served.

Tora looked him directly in the eye and told him to take his place in the queue –just like everybody else.

The official was astonished that a mere native had just ordered him to wait in the queue. When he refused to budge, Tora stood firm.

The official complained to the DO – Ratu Kamisese Mara, (Fiji’s first post-colonial Prime Minister). What happened after that is unclear.

But as one academic recently shared with this scribe, Mara himself was known to have harboured his own resentments against colonialism and might have even been smiling quietly at the viavialevu attitude of the underling in his command.

It therefore comes as no surprise that Tora looked up to figures like Nasser, Fidel Castro and the great Martin Luther King for inspiration. He could relate to their struggles for equality and justice. I remember him being quite upset the day King was assassinated.

A spark of the wilful spirit within was evident from early on.

At Fiji’s elite Queen Victoria School [QVS], there was a story about Tora that had evolved into legend by the time Savenaca Siwatibau (former Reserve Bank Governor of Fiji) arrived at QVS in the sixties.

During a family visit to my home in Melbourne, Siwatibau regaled me on the following tale. Tora was rostered on dining room/kitchen duties one day. His supervisor was the formidable martinet, Semesa Sikivou – later Fiji’s Ambassador to the UN. Master Sikivou issued strict instructions – the tables and chairs had to be cleaned and put in place by the end of the day.

Instead of attending to his duties, Tora picked up a bucket and fishing rod and headed for a nearby river.

He did not return until long after dark – bucket brimming with fish. Sikivou, who had been waiting for him, pounced on the boy, with a furious reprimand: “Did I not tell you, you were to finish your job by the end of the day?”

To which the boy replied firmly: “Sir, you said the end of the day and it’s not the end of the day. The day ends at midnight and I still have a few hours left.”

Not surprisingly, Sikivou wasn’t exactly enamoured with the boy’s logic and roundly sent him off to detention.

In the general election of 1963, Tora ran as the youngest candidate against one of Fiji’s Paramount Chiefs, Ratu Penaia Ganilau, later to become Governor-General and Fiji’s first post-coup President. Ganilau ended up defeating him by six thousand-plus votes.

Tora had laboured long and hard during the campaign period. He would walk on foot from village to village in the western part of Fiji where, in a number of villages, he was violently ejected. As he recalled in a conversation I had with him, some villagers literally stoned him, infuriated over his audacity in challenging a Paramount Chief.

The average iTaukei at that time believed and, I would suggest, even now to a degree, still subscribe to the notion of the divine right, or Mana, of the Chiefs to rule.

In her book, Caste – the Lies that Divide Us, Isabel Wilkerson writes that caste “embeds into our bones an unconscious ranking” of human beings and lays down the “rules, expectations” of where one fits in society’s ladder.

When that status quo is challenged, it can be deeply disturbing – even for the subordinate class at the bottom rung of the ladder. Wilkerson writes, it is not uncommon for this class to defend the same hierarchy that oppresses them.

Apisai Tora was a man who elicited only two kinds of emotional responses from people. They either reviled him with a murderous passion or they admired him with nauseating sycophancy. There was no middle ground.

This effect on fellow human beings was, by equal measure, a reflection of an unyielding application to everything in life and a brutally forthright approach which did not endear him to Fijian sensitivities.

It would be too simplistic to throw labels such as ‘racist’ at him for here was a creature of contradictions – an intriguing paradox that defied a templated stereotype.

An iTaukei activist, custodian of a traditional status within his Vanua (traditional area) and, for good measure, a Muslim convert, he numbered among his closest friends and associates a diverse and varied group.

Former Leader of the Indo-Fijian-dominated National Federation Party and Lawyer, Siddiq Koya, was a trusted mentor and lifelong family friend.

Following Koya’s passing in 1993, the bonds of friendship continued with Koya’s children — Shainaz, Faizal and Faiyaz – and widow, Amina, who he would take the time to visit with bundles of dalo and render what assistance was needed.

The coup

In his eulogy at Tora’s funeral on August 14, Faizal Koya took Tora’s critics to task, rebuking their familiar refrain that Tora was a racist.

The Indo-Fijian communities, he said, particularly in the Fiji’s West where Tora hailed from, embraced him as a generous individual – possibly a fellow traveller in the struggle for equality.

To his detractors however, Tora’s principal role in the iTaukei Movement and the coup of 1987, puts paid to any such redemptive notion.

But as retired ANU [Australian National University] academic Professor Brij Lal, reminds us, to put things in perspective, the coup was not the work of any one individual.

There is little doubt the grassroots base behind the coup was bolstered by the silent blessing, and even the active participation, of the autocrats at the very top of their hierarchy.

The above notwithstanding, Tora’s role in the ’87 coup and his subsequent volte-face in embracing multiracialism, continues to overshadow any discourse on his legacy.

In a similar vein, any narrative on Fijian politics is forever sullied by a coup culture that robbed a nation of its potential at independence, relegating it to a tinpot republic status.

Engaging with the iTaukei

When it came to Tora’s engaging with the iTaukei, it was primarily through the prism of the Vanua at which time, the traditional hat was donned along with its customary expectations and responsibilities.

Tora was never under any illusion about what he viewed as the communities’ challenges.

As a landowner in the Sabeto sugarcane belt, he employed sugarcane workers to harvest and cut the cane for him. This was backbreaking work that began before dawn and continued through the blazing heat of the day to sundown.

He once told me that when he hired Indo-Fijian workers and instructed them to meet him at his home at 5 o’clock in the morning, they arrived several minutes before the appointed hour. And for as long as they were employed, they would continue to do so on a consistent basis.

To his mind, it spoke volumes about their reliability, their discipline and their commitment to the task at hand.

As for the iTaukei workers, he said, some would turn up late and some wouldn’t turn up at all.

iTaukei he felt, needed to cultivate the patience of the Indo-Fijians, who had the capacity to save their hard-earned cash, and persevere through long periods of time towards an uncertain future.

As a general rule, the iTaukei live in the present, and when you are preoccupied with the present, there will be little incentive to invest in a future that you can neither see nor imagine.

Indo-Fijians, by contrast, live for the future. They can defer immediate gratification and sacrifice the present for an imagined future brimming with opportunities and the promise of a more prosperous life. It is this imagining and goal setting which motivates their work ethic and drives their commitment to bettering their lot in life.

Historically, it is made even more urgent by their perceived status as outsiders and the festering sense of insecurity that stems from it.

This has been one of the essential differences sitting at the core of the iTaukei -Indo-Fijian cultural divide – and one which Tora would have been acutely conscious of.

That said, he was painfully aware of the cultural obligations – or kerekere to which Fijians seem perpetually yoked. The Vanua’s expectations for its constituents to contribute cash in the never-ending cycle of human events – from births, deaths and weddings – is the enduring narrative of the iTaukei.

Tora believed this cultural obligation effectively precluded the iTaukei from full economic participation.

Later Life

Throughout the 1990s, Tora ran unsuccessfully in a number of elections, signalling what political commentator Bimal Chaudhry, so fittingly describes as “the beginning of his fate as a star outside the galaxy – out of Parliament yet pulling the strings”.

Tora did indeed morph into a star out of the galaxy but his status in the Vanua ensured he had a full schedule and a constant stream of human traffic that approached him for traditional advice, referrals, money to pay for school fees, transport costs, tabuas for a reguregu or mats for a wedding. Other times, the people he had helped would return their gratitude with gifts of food – the fruits of their labour – cooked yabbies packed in cardboard boxes, fish, taro and sumptuous other delights.

In later life, Tora assumed a status as a kind of go-to guru as politicians and activists sought his advice.

I was always touched by the villagers who, over the years, trekked long distances from remote areas of Viti Levu to see Tora and unburden their troubles on him.

I remember distinctly one afternoon back in 1979, when a young Fijian boy had travelled a fair distance from his home to deliver a handwritten note to him in his home in Natalau Village.

It was a letter from his grandmother telling the old man that she had run out of food and money and had nothing left to feed her numerous grandchildren. Could he help her out?

None of us had ever met this woman.

Straight away, Momo instructed that we fill up the family car with bundles of dalo, an entire sack of rice, sugar, and sundry other grocery items.

And off we went in the car with the young boy navigating, to some unknown destination.

It seemed like the trek into a separate universe, the tarsealed road having long disappeared behind us as the car spluttered through rough terrain.

Finally we saw the house. A rundown shack that was barely standing.

When the grandmother saw us, she almost fell to her knees as she approached Momo, and thanked him over and over for this act of kindness. I lost count of the number of children who surrounded us that day but she was their sole caregiver.

This episode remains fresh in my mind as if it took place yesterday. It warms me to think that the old man spoke her language. He knew completely the troubles of her heart. He felt her pain and suffering – because he too had been there.

Tora is survived by 10 children, several grandchildren and great grandchildren.

May the old Lionheart rest in eternal love and peace.

This article was updated on 31/8 at the request of the author.