A proliferation of security deals in the Pacific may be harming rather than helping the region and increasing the risk of conflict, observers have warned.

Geopolitical tensions were among the most hotly debated topics at the recent Pacific Islands Political Studies Association conference in Wellington.

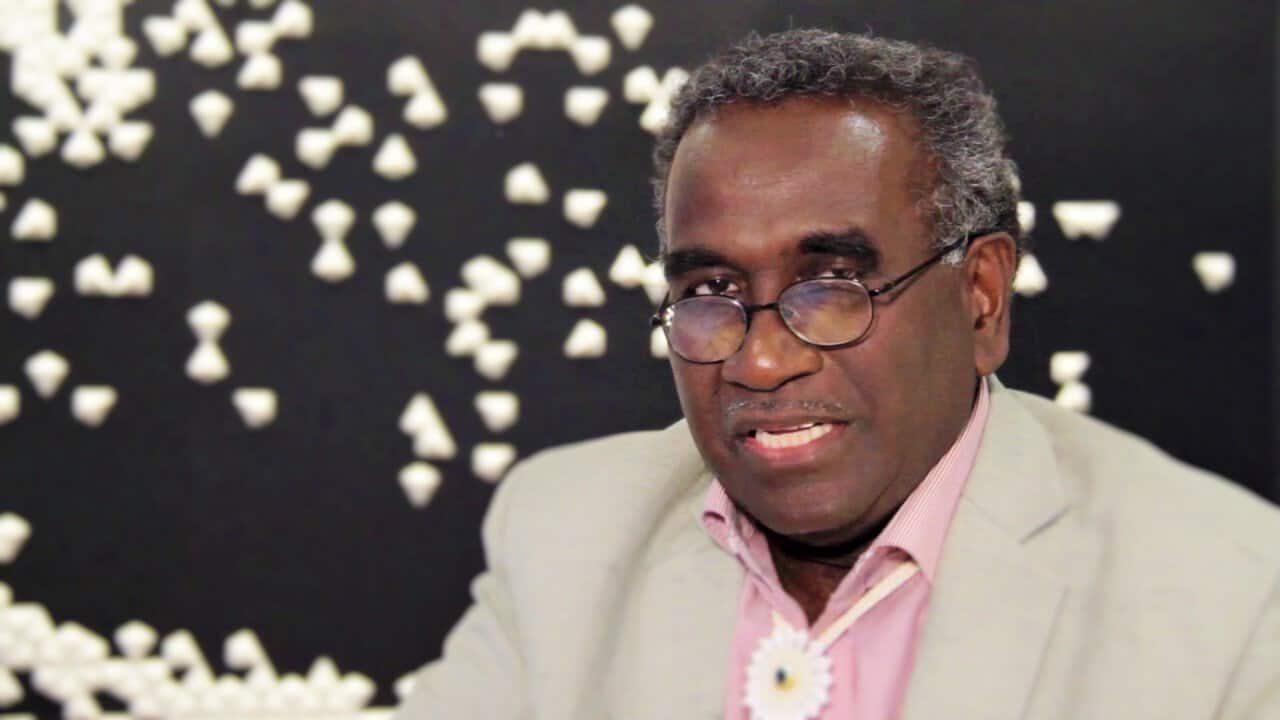

In his keynote address, Solomon Islands National University vice chancellor Transform Aqorau said the Pacific was “not a chessboard for global competition”, but a collection of sovereign states with their own aspirations whose voices needed to be heard.

Aqorau said Great Power competition in the region had echoes of the Cold War, when the Pacific was treated as a space for strategic denial.

“The same language of ‘spheres of influence’ is re-emerging, placing enormous pressure on our leaders to ‘take sides’.”

Talk about China infiltrating the Pacific ignored the fact the country’s people had been present in the region for a long time, with many of Aqorau’s peers having gone to school with the children of Chinese families who had lived in the Solomon Islands for generations, he said.

“The fear that Pacific nations are merely passive pawns in a great power contest does not align with the historical and cultural realities of our region.”

While Pacific leaders had traditionally used external rivalries to benefit their own people, the balancing act was becoming harder to manage as geopolitical tensions increased.

A confrontation between the United States and China over Taiwan could have ripple effects for the Pacific, with countries pressured to take sides in any conflict.

Aqorau said Pacific nations need to strengthen regional institutions like the Pacific Islands Forum to present a united front, while diversifying partnerships beyond the US and China to middle powers like Japan, India and the European Union.

With growing concerns about militarisation, there had to be a Pacific-led approach to security that emphasised peacebuilding and humanitarian operations rather than military competition and expansion.

“Rather than allowing external actors to impose security frameworks that do not reflect Pacific realities, our leaders must advocate for a security architecture that aligns with our cultural, social, and environmental contexts.”

The recent surge in defence deals within the Pacific has been captured by a Pacific defence diplomacy tracker created by Massey University and the Griffith Asia Institute, with nearly 800 different diplomatic activities since 2018.

Dr Anna Powles, the tracker’s co-creator and a senior lecturer at Massey University’s Centre for Defence and Security Studies, said the research raised concerns about what Pacific countries might be asked to do in the event of an armed conflict in the wider region, due to their obligations under security deals they had signed with various countries.

With the proliferation of defence deals, the New Zealand government has been looking at ways to implement specific ‘strategic trust’ or national security clauses in its agreements with Pacific nations, as reported by Newsroom last week.

In his speech opening the conference on Wednesday evening, Foreign Minister Winston Peters said New Zealand would need to “reset” its relationship with the Cook Islands, finding a way “to formally re-state the mutual responsibilities and obligations that we have for one another”.

However, Powles said such strategic denial clauses could undermine New Zealand’s relationships in the Pacific, while the Government would need to have both the capacity and the will to enforce such clauses if they were implemented.

Dr Henrietta McNeill, a research fellow at the Australian National University’s Department of Pacific Affairs, said bilateral security deals were meant to provide stability but instead created increased competition, “with each promising to deliver more equipment, more resources … more security personnel than the alternative power”.

McNeill said transparency had been an ongoing problem with the deals, citing the example of the China-Solomon Islands security agreement signed in 2021 that was never formally released.

“The clandestine nature of that pact exemplifies how non-transparent bilateral security deals engender public distrust and undermine public institutions”

It was not just China that had kept the public in the dark: a deal between Australia and Papua New Guinea that would fund an NRL team for the latter, provided it signed a parallel ‘strategic trust’ agreement, had not been released on commercial grounds.

Many security agreements had actually invited domestic conflict, McNeill said, with the Solomon Islands deal the most obvious example.

“There’s this tit-for-tat where China provided the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force with training and dubiously replica guns for training, Australia then donated semi-automatic rifles and 13 vehicles, China then donated water cannon trucks, motorcycles and cars and the cycle continued.”

An Australian-led mission had in fact taken away the Solomons police force’s weapons to help guard against ethnic violence between 2003 and 2017 – only for the police to be rearmed less than four years after the mission officially ended.