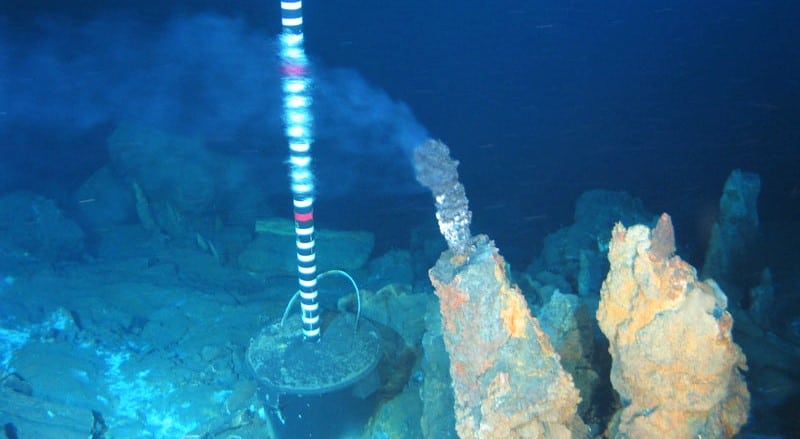

The extraction of deep seabed mining resources on an industrial scale at incredible depths is a new frontier with many unknowns. But the potential gains are immense. Deep sea deposits contain manganese, cobalt, nickel, gold, silver, copper, and a wide range of rare earths. These rare earth metals are vital to make batteries and are essential to the green energy transition.

The economic potential of deep seabed mining has been identified in many of our Pacific neighbours’ waters including those of Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Tuvalu, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Cook Islands, Tonga, and Niue.

Licences are being issued by several island governments. But all this comes with potential risks. While the pioneering companies may be precautionary in their developments, cowboys and illegal operations will surely follow.

It’s going to be important for the islands to develop stringent national deep seabed mining legislation, surveillance capacity and policies that reflect regional and national development strategies and meet environmental standards.

The Pacific Island countries should agree on minimum terms and conditions for seabed mining activities within their areas of jurisdiction. This might mean they need to establish a company office onshore in each country, where such ventures would exist, as a point of legal contact and for management and accounts.

Regional environmental and safety standards, including levels of insurance cover, must be met and a requirement for port clearances of imports and exports for seabed mining ventures in national waters as a term of licence. This should extend to a regionally agreed minimum scale of royalties.

There should be a requirement for regional observers on mining platforms and support craft to monitor all activities and record a range of operational and environmental parameters. These observers would be the region’s eyes when it comes to deep seabed mining. Ore carriers should require clearance in a nominated port or inspectors placed on the mining platform to monitor export volumes and assay the ores being exported as a term of a licence.

This is typically done by a third party for onshore mines to protect both the state and buyer. In the case of seabed mining, where royalties may apply and the range of target minerals is wide, it would be critical for this to be independently done.

Minimum terms and conditions for deep seabed mining in the region would ensure national legislation wasn’t undermined by seabed mining nations or see island countries played off against each other. The islands have limited capacity and experience regionally to deal with this issue, (most don’t operate land-based mines), so are vulnerable to unethical exploitation, as seen in other extractive sectors.

That’s why Australia should encourage Pacific leaders to establish a regional deep seabed mining agreement that will assist in strengthening the region’s capacity to set and monitor minimum standards to ensure seabed mining doesn’t cause any unacceptable damage to the marine environment. This would pave the way for the island countries to demand compatibility in deep seabed mining in high seas areas adjacent to their own ocean zones.

Here, it’s worth making a distinction between deep seabed mining in international waters and seabed mining in a coastal states’ offshore estate. The International Seabed Authority with 167 members (including the EU) in Jamaica regulates activities in the area beyond national jurisdiction. The ISA is developing a mining code to manage and monitor deep seabed mining activities in the area beyond a coastal state’s jurisdiction. Thirty one exploration contracts have been issued by the ISA, including to the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, and Tonga

The president of Palau has started a petition for a ten year pause on deep seabed mining activities while more research is done. Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has noted that she’s “concerned about the broad and unknown environmental impacts of deep-sea mining” and that DSM shouldn’t take place “unless strong environmental regulations are in place.” But now is the time for us to stop dithering on seabed mining. Doing and saying nothing is no longer a credible policy position.

It’s too late to back a seabed mining moratorium that would slow down exploration initiatives, which now have momentum. Instead, we should offer support and provision of commercial survey vessels for environmental surveys and monitoring. We should help the islands monitor environmental rules for mining underwater, just as we do for monitoring the impacts of removing minerals on land.

We should also do this for geostrategic reasons. China has long been prepared for the DSM industry to take off. They’ve developed state-of-the-art technology for large-scale extraction of critical minerals from the ocean floor. Cost won’t be an object as Chinese firms try to elbow out the competition. Control over DSM, and more especially continued dominance over the reserves of rare earths, will continue to give Chinese manufacturers an advantage in scaling up production of new products like electric vehicles.

Survey and development work continues to be conducted as “research” in readiness for full scale commercial developments. We can’t afford to lose any scramble for the seabed in our neighbourhood to malign actors who don’t care about environmental studies or basic compliance.

Look at the damage done to coral reefs in the South China Sea caused by Chinese dredging for artificial islands, or the numerous instances of environmental destruction at their mining operations at home, in Africa and places like Myanmar.

Australia, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and Canada are all Partners in the Blue Pacific to assist Pacific priorities. The PBP group should support financing for a regulated deep seabed mining industry for the long-term benefit of our Pacific neighbours.

Australia should be at the forefront of this emerging industry in our neighbourhood. If we can help show that Pacific Island countries are responsibly balancing the best interests of all involved, we’ll be in the best position to ensure that our advisors and operators get the phone call when a member of our Pacific family wants to start a deep seabed mining operation.

Anthony Bergin is a senior fellow at Strategic Analysis Australia and an expert associate at the National Security College. Maurice Brownjohn is an independent consultant on fisheries and marine resource management. A version of this article appeared in The Australian 18 June 2023. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of this publication.