Papua New Guinea is an incredibly diverse country. This is a source of great pride to most Papua New Guineans, and rightly so. Each of PNG’s more than 800 languages is a world, and carries the joys and pains told by parents to children across hundreds of generations. Equally impressive is the way that Papua New Guineans live with this diversity: a deep respect, a mutual recognition of kastom, and fluency in translating between traditions. It doesn’t always work but the difficulties should also be put in perspective. Europe, with the equivalent of the linguistic diversity of just Madang province, fragmented into dozens of states and fought devastating wars.

I begin with this consideration because I want to stress that an ability to work with differences is one of PNG’s core strengths. But we need to talk about how this genuinely praiseworthy set of values can be exploited to look past deepening political inequalities.

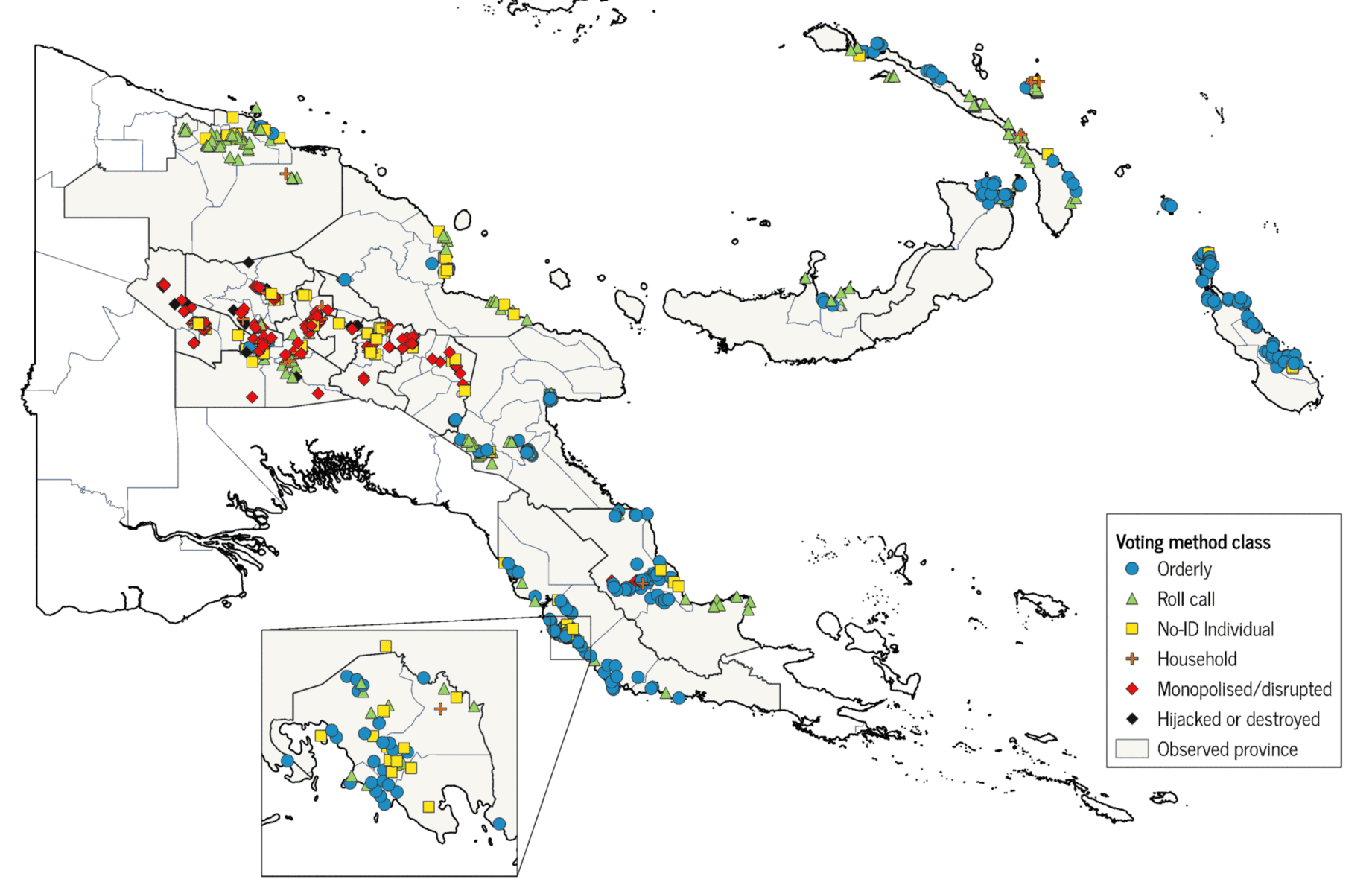

Recently, the Australian National University’s Department of Pacific Affairs carried out an analysis of electoral observation data from 2007 to 2022 examining the distribution of some basic patterns of polling, or “voting methods”. What we found were profound, and generally geographic, differences in the degree to which Papua New Guineans are able to participate in free and democratic elections.

In some places, elections mostly follow the law: people queue up, they undergo voter identification and if successful, they vote. There are problems, notably with the electoral roll, but at these polling stations it is individuals who vote, generally in a secret ballot, and at a time convenient to them. We classify such polling as “orderly”.

In other places, individuals lose their right to choose when to vote. Instead of queuing up, names are called from the roll. A “roll call” might seem to involve only a tiny change, but there are consequences. Voters might have to wait all day to hear their name, which is detrimental especially to women and workers. If someone’s name isn’t called and that person thinks this is a mistake, they have to step in front of someone whose name has been called. The roll call effectively co-opts the community’s frustration with the electoral roll in an attempt to limit complaints. But the attempt often backfires, because the roll call broadcasts the names of the absent persons to everyone within earshot, which facilitates voting under someone else’s name.

In other areas, the electoral process breaks down much more substantially. Some polling stations abandon voter identification, but individuals still vote. We call these “no-ID individual” stations. People might be happy to be able to vote, but abandoning the roll makes multiple voting easier and this creates incentives for candidates to stack polling stations. In some cases, the situation degenerates into a scramble for ballots. Individual voting without a roll seems to be unstable.

What happens next depends to a large extent on the balance of forces in an electorate, but in general there is a move away from individual voting. In some cases, there are traditional ways of organising group votes: household heads and clan leaders vote on behalf of their kin. We call this “household voting”. This used to be common, but more recently we have seen a move towards either an anarchic scramble or candidate control of polling. This often reduces most of the community to bystanders. These are “monopolised/disrupted” polling stations.

Entire books of ballots are up for grabs in these cases, which creates a great deal of tension, leading to violence and ultimately to efforts to pre-empt rivals by hijacking ballot boxes and either tampering with or destroying them. In such “collapsed” stations, as one observer put it, the voters “did not see even the colour of the papers”.

These different voting methods have deep political consequences. In some, voters have to be persuaded. In others, there is a contest over ballot papers, sometimes decided by force.

In Figure 1, we show the distribution of these voting methods at 755 locations observed in 2022. There are two things that must be noted. First, the Highlands face far worse conditions than other regions. But second, the Highlands are not homogeneous. There are some relatively good polling stations to be found there, even in areas that are otherwise seriously distressed. We often find relatively good polling near police stations, hospitals and civil servants’ residences. Indeed, in the Highlands there might be less than a few kilometres between a flawed election with poor rolls but individual participation, and an election in name only in which candidates fully control the process.

We should be clear about what this means. The PNG constitution establishes an individual’s right to vote. The vote must be a free choice. In practice, we see this right is denied on a large scale. Our surveys are not randomised so we cannot estimate the total number of people who are denied a fair chance to participate, but it is very large — perhaps half the total voting population is at risk. What we can say with confidence is that this denial of rights is unequally distributed, both between the Highlands and everyone else, and within the Highlands between a lucky few and an unlucky many.

This has severe consequences in the first instance for individuals who cannot vote either because of failure of the electoral roll or because the legal process has been abandoned — but also for everyone else. It is an illusion that the problems concentrated in the Highlands are problems only for the Highlanders. The winners of these starkly different elections all go to the same parliament. Desperately-needed reforms are in the hands of all the MPs but, for many, the incentive structure that exists at polling time is adverse to addressing fundamental problems.

Diversity should not be used to mask what is, in fact, a profound problem of inequality. What we see in the Highlands is not samting blong ol Hailans. It is a structural problem that has emerged in the Highlands but could very well spread further. We know this because it has spread within the Highlands, which is itself extremely diverse. The deterioration in electoral conditions there has accelerated recently, and with this a notion of Highlanders as essentially different is becoming entrenched. This is unjust, as Highlanders are disproportionately disenfranchised, and it is an error, as the situation in the Highlands is the outcome of institutional collapse. Unless this is recognised as a joint problem for communities across PNG, there is a risk of worsening ethnic polarisation. The fragmentation of electoral organisation we have recorded is perhaps the greatest test PNG has yet faced to its core value of mutual respect in diversity.

Disclosure: This research was supported by the Pacific Research Program, with funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are of the author only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy

Centre at The Australian National University.

Dr Thiago Cintra Oppermann is a research fellow at the Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. He is an anthropologist working on the history and social organisation of Bougainville, and electoral politics in Papua New Guinea.