Research published in the science journal Nature Ocean Sustainability has found deep-sea mining is likely to pose a threat to bigeye, skipjack, and yellowfin tuna populations in the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Climate change is pushing migratory tuna populations into geographies that overlap with areas allocated for deep-sea mining, according to the study, “Climate change to drive increasing overlap between Pacific tuna fisheries and emerging deep-sea mining industry,” published 11 July.

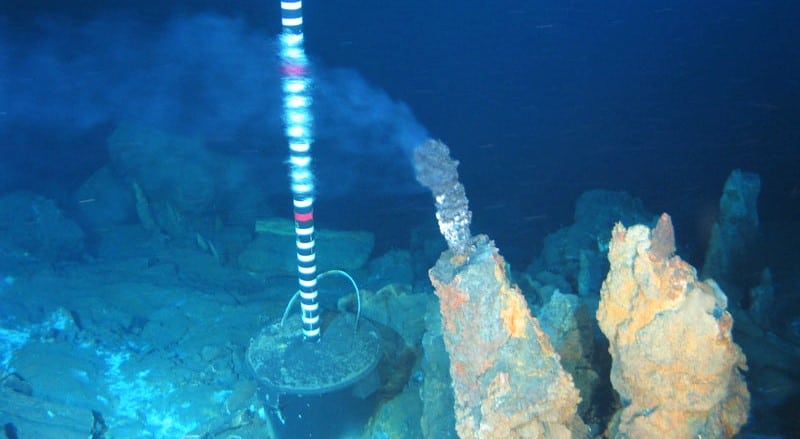

Mining in areas where tuna is prevalent could cause harm in various ways, including through discharge plumes that disrupt feeding and breathing, elevated levels of toxic metals in the water column where tuna breathe and eat, noise pollution that could interfere with feeding and reproduction, and increased vessel operations potentially affecting tuna behaviour.

“This work shows the need to consider the effects of mining on fisheries and consider mining regulations not just for the current environmental conditions, but also for future climate projections,” South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute Researcher Jesse van der Grient, one of the study’s co-authors.

The study focused on the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, a maritime region southeast of Hawaii containing 1.1 million square kilometers (424,712 square miles) of deep-sea mining exploration contracts. Researchers ran scenarios involving two different projections on how climate change would impact the range of migratory tuna by 2050, and found the bigeye tuna population in the area overlapping with the areas designated for mining would grow by 10 to 11 percent, the skipjack population would increase 30 to 31 percent, and the yellowfin population would grow 23 percent.

“The high seas harbor a trove of biodiversity, and there are critical sectors of our economy that depend on this biodiversity,” University of British Columbia Post-Doctoral Research Fellow Juliano Palacios Abrantes, another of the study’s co-authors.

“There is already uncertainty about the impact of climate change on the health and geographic range of tuna. Deep-sea mining will only add to this uncertainty, further threatening tuna species and associated fisheries.”

The same day the study was published, a letter signed by the Global Tuna Alliance, Fishwise, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program, Mar & Comercio, Joseph Ropertson Aberdeen Ltd., the Sustainable Seafood Coalition, and Lusamerica Fish called for a pause in deep-sea mining development.

“In the vast expanse of the high seas, critical for tuna species, we find ourselves sailing into uncharted territory with the unknown risks posed by deep-sea mining,” Global Tuna Alliance Executive Director Daniel Suddaby said.

“From threats of prey food shortages due to disrupted midwater ecosystems to the potential upheaval of migration patterns caused by mining disturbances, we must navigate this uncertain landscape with caution. With climate change scenarios further complicating the picture, we cannot underestimate the stakes involved.”

The groups called for the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of deep-sea mining to be more thoroughly analyzed before it is allowed to proceed.

“As producers, fishers, retailers, suppliers, and managers of sustainable seafood, we recognise the critical role of healthy and productive ecosystems in supporting sustainable fisheries and seafood supply chains,” the letter said.

“As such, we are deeply concerned about the aforementioned potential impacts of deep-sea mining on the health and resilience of the ocean, and the consequences it might bring in terms of the quality and quantity of seafood supply and the communities they support.”

The publication of the study and letter come in advance of a meeting of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the international body that regulates mineral activities on the high seas, taking place in Kingston, Jamaica from 10 to 23 July. At the meeting, ISA member-countries are expected to considering designing and implementing deep-sea mining regulations

More than a dozen ISA member countries have called for a precautionary pause, moratorium, or ban on deep-sea mining until scientific research can more clearly predict its impacts, including France, Germany, Spain, New Zealand, Palau, Fiji, and Costa Rica.

In the United States, the U.S. states of California, Oregon, and Washington have already implemented bans on deep-sea mining, and Hawaii’s legislature is currently debating a similar law.

“These fishing grounds may be distant, but the food they produce is consumed by millions,” University of California, Santa Barbara Professor Douglas McCauley, a study co-author and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, said.

“We would be horrified at dumping mining waste across our food-producing regions on land. We shouldn’t be rushing into a decision that could significantly harm ocean ecosystems essential to planetary health and global food security,” he said.