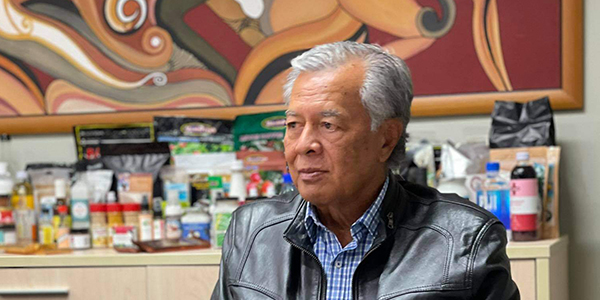

If there was a time when leadership was critical for Pacific regionalism, it would be now. A new Secretary General (SG), former Cook Islands Prime Minister, Henry Puna, is taking over the rein of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS). But the organisation, Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) he will manage, is weakened by the withdrawal of five Micronesian members following Puna’s election to the position. There is however the prospect of the return of the aggrieved five should the ratification processes in the five countries concerned favour such a return.

The issue of leadership of the . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...