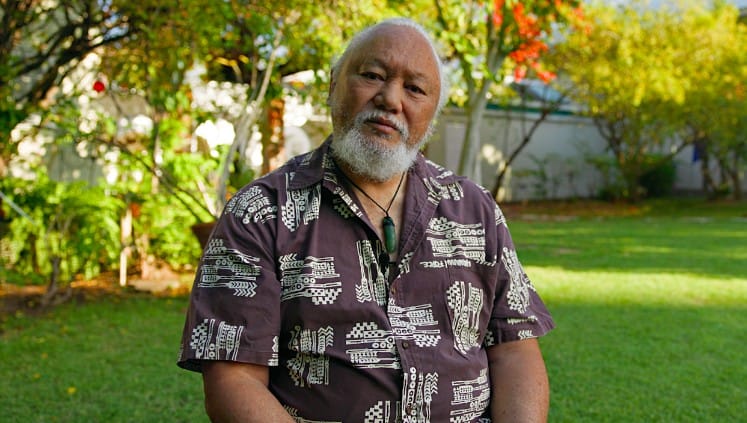

Solomon Kahoʻohalahala opened Thursday’s Deep Ocean Symposium, an academic conference at the University of the South Pacific Cook Islands campus, with a chant.

Spurred by the blowing of a conch, the Hawaiian cultural authority recited from the Kumulipo, the seminal record of the genealogy of his people. In the darkness, he chanted in his language, is birth. In the mud is where life begins.

“Let me begin by telling you a story about our queen,” he said when he finished, addressing a room packed with people interested in the deep ocean, from mining companies exploring the metal-rich nodules of the Cook Islands’ seabed to citizens concerned about what those companies are proposing to do.

Kahoʻohalahala explained that when the United States government overthrew the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani was imprisoned in her bedroom. In her isolation, she dedicated herself to translating the Kumulipo, a 2,104-line chant perpetuated orally and from memory, into written English. He held up a copy.

“I have to believe that she had, perhaps, in mind times like these,” he said, outlining the state of the world: climate change, unprecedented storms, an ocean that is stressed. “I carry this around with me all the time as a reminder of the things I need to be grounded in.”

The Kumulipo, he said, tells a creation story spanning millions of years, beginning in the mud of the deep sea that carried the life force which would later spawn humans.

Kahoʻohalahala, a former politician, explained that he regularly attends meetings of the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica, which regulates the seabeds of international waters. The discussions at those tables, he said, centre on the properties of polymetallic nodules, the ecosystems that support them, and the economic value of extracting them. He shows up to ask questions about “the value of the place in which life is created”, he said.

“Perhaps not only oxygen is created in the deep sea,” he said, setting the stage for a presentation that would follow, “but life itself.”

Kahoʻohalahala was one of two keynote speakers at the Deep Ocean Symposium, hosted at USP and organised jointly by Te Puna Vai Marama, the Cook Islands Centre for Research, and Te Ipukarea Society. The other was Dr Andrew Sweetman, whose work ignited a global debate in recent months, and could, perhaps, in Kahoʻohalahala’s view, corroborate the Kumulipo.

Sweetman, who leads a research group at the Scottish Association for Marine Science, published a paper in July that suggests polymetallic nodules – the rock-like formations being targeted for the valuable metals they contain – actually produce oxygen. Until the publication of his research, which has been hotly contested by mining companies, scientists believed oxygen sank through the ocean from surface to seabed.

Sweetman’s team has, for 20 years, been developing and deploying lander systems that measure the respiration, or breathing, occurring underwater through sensors that track the oxygen in the more than 200,000 litres of water passing through them over time.

Within the last decade, he said, they have been perplexed to discover “very, very high rates of oxygen production” occurring in the deep sea. Production would increase in areas rich with polymetallic nodules and decrease in areas where there are none.

“For about nine years, I didn’t believe this data,” Sweetman said. “I thought there was something I was doing wrong.”

He cycled through a litany of criticisms levelled at his paper since its publication, explaining that he tested for all of them: the lander introduced oxygen (it didn’t), the lander brought the oxygen with it (the oxygen decreased on the way down, then increased again at the seafloor 34 hours later), the test kickstarted the production process (Sweetman doesn’t know).

“We literally went through every single thing we could think of,” he said. “We thought, it must be something we’re doing. We’re introducing oxygen somewhere. We went through all of these thought processes and eventually we just had to conclude that there was something going on.”

If the nodules produce oxygen, he asked, what happens when they’re removed?

He acknowledged how much he doesn’t know, and that he’s uncertain whether oxygen plays a pivotal role in environments of the deep or not. He ended on a note of resignation: “Over the last 11 years I’ve been trying to disprove this, and I cannot do it anymore.”

Nine other speakers presented at Thursday’s symposium also, among them environmentalists, a lawyer, an economist, researchers, and an activist. The picture they painted of deep-sea mining looked different than the picture painted at last month’s Underwater Minerals Conference, the weeklong event hosted by the International Marine Minerals Society that largely celebrated and anticipated deep-sea mining.

September’s conference, entry to which cost US$1000 at the door, attracted investors, CEOs, and technologists. Presenters spoke of science that proved the environmental impacts of mining will be negligible and technologies that will further reduce these impacts. There was a general sense of buoyancy, optimism, and hope.

Thursday’s symposium, by contrast, highlighted alternative views, some of them ringing like bells of warning. This was the whole point, according to the event’s organisers: to introduce other points of view in order that the voters and taxpayers of the Cook Islands can make better-informed decisions. “Te Puna Vai Marama has a mandate to make research accessible to the community,” said Professor Heather Worth, the research institution’s director. “This was a great opportunity to do so.”

Professor Chris Fleming, who teaches economics at Griffith University, spoke about the economic feasibility of deep-sea mining. He critiqued a cost-benefit analysis conducted by consulting firm Cardno and The Pacific Community, which suggests that while deep-sea mining will add “very little direct benefit to the people of the Cook Islands, very few jobs, and very little income to Cook Islands companies”, it could generate US$467 million for the country, largely from royalties.

“If you see that headline number, you’d rush into [mining],” Fleming said. “You’d do it. So, let’s unpack it a little bit and see how they got this number.”

The number, he said, relates to a best-case scenario, which he said “seems strange” because projects generally fall short of the best case. The number also doesn’t factor in the value of cultural assets, the cost of discharging mining waste, the cost of modifying ecosystems, costs associated with climate change, or potential costs to the commercial fishery. The number also assumes deep-sea mining will affect tourism negligibly.

“I think that’s the kicker for you guys in the Cook Islands,” he said of the last projection, noting it’s “fairly inconsistent” with one of his own studies. In Fiji, his research team asked visitors two questions. Would they recommend Fiji as a travel destination? Ninety-seven per cent of respondents said yes. Would they recommend Fiji as a place to visit if the government was permitting deep-sea mining? The number dropped to 44 per cent. Sixty-two per cent of respondents believed deep-sea mining would negatively affect their diving or snorkelling experience – a view that Dr. John Parianos of the Seabed Minerals Authority said would likely change with increased access to information.

Fleming also highlighted recent developments: mining costs have gone up, metals prices are either flatlining or declining, and major corporations and financial institutions are refusing to deal in deep-sea minerals.

“The profitability of deep-sea mining is really beginning to be questioned,” he said.

Duncan Currie, an international environmental lawyer, offered his thoughts on the legal systems and processes occurring at the International Seabed Authority, which is working toward global regulations for seabed mining, and in the Cook Islands.

He highlighted what he views as structural problems with the international authority: decisionmakers meet behind closed doors, voting processes are “arcane”, and perhaps most importantly, the authority cannot amend a contract based on new information without the express consent of the country that signed it. In other words, he explained, once a contract is signed, there is “no going back”.

He issued a warning about the exploration currently occurring, which costs tens of millions of dollars, noting corporations tend to sue governments that deny them permits after investments have already been made.

“Once you get involved in this situation and there’s a lot of money involved, you’re opening yourself up to the real possibility of litigation … when people lose money, they’re going to want their money back,” he said. He advocated for an “open, participatory system” of developing rules, laws, and contracts. Alex Herman, commissioner of the Seabed Minerals Authority, took the microphone to explain that her office has regularly consulted with the communities of the Cook Islands.

Alanna Smith, the director of Te Ipukarea Society, raised questions during her presentation about whether that consultation was meaningful. She explained that her organisation had submitted comments in response to mining regulations circulated this year that did not appear to be considered.

“To find out in the Cook Islands newspaper that it was passed through and [there was] no feedback was a real slap in the face,” she said. She added that her organisation advocates for changing the term “national interest” in seabed-related legislation to “public interest, so that decisions still have power from the people”.

Smith also drew a distinction between “science to understand” and “science to exploit”, noting that in the third year of a five-year exploration period most of the gathered data pertains to nodules.

Representatives of the Seabed Minerals Authority – Dr John Parianos, Rima Browne, and Tanga Morris – spoke about what it’s like to gather that data.

“It’s not a holiday, that’s for sure,” said Browne, who was the chief scientist aboard a recent expedition called the Women In Science Expedition (WISE). Aimed at developing the skill sets of 10 female Cook Islanders, the expedition travelled to two potential mining sites. Participants deployed box corers and multicorers, equipment that collects samples from the seafloor. They also dropped cameras, leaving them there for up to six hours to collect images of what’s happening five kilometres deep. Training young people who will guide and lead the development of a deep-sea mining industry in the Cook Islands is one of the priorities of the Seabed Minerals Authority, Parianos explained.

Merita Tuariʻi, a senior research fellow at Te Puna Vai Marama, shared results of a survey that circulated digitally in September via email, Facebook, text message, and this newspaper. Questions, which were based on polls designed by Ipsos in Europe, were answered by 750 people – a sample size that Shona Mato Lynch, who manages deep-sea mining company CIC Limited, pointed out can’t represent the whole population. Fleming responded that this is a larger sample size than most polls.

Tuariʻi explained that 48 per cent of respondents to the survey said they don’t support companies exploring the Cook Islands’ seafloor, whereas 42 per cent said they do. Sixty-four per cent of respondents, the majority of which were women, said they opposed deep-sea mining.

“We found that men and boys were more likely to support deep-sea mining and women and girls were more likely to oppose,” Tuariʻi said, suggesting that perhaps this is because more men are involved in money-making activities.

Nearly three-quarters of respondents, she said, believe mining will disrupt deep-sea environments. About one-third said they are not convinced by the argument that deep-sea mining for minerals isn’t necessary because of innovations in technology and systems for recycling metals. Around 90 per cent of people who indicated they support mining believe the industry will be a boon for the Cook Islands economy. One-third of respondents who support mining also agree that the deep ocean is culturally and spiritually significant.

“This appears contradictory but might be related to the narrative that minerals in the deep sea are a gift from God,” Tuariʻi said.

John Hay, a Nobel Prize-winning professor at USP and Griffith University, declared when he reached the podium that he is “personally in favour of exploiting the deep-sea minerals of the Cook Islands”, then spent his allotted time redefining exploitation as use rather than extraction.

By using nodules as a tool in the work of conservation, he argued, the country could still make money off of them. He discussed other scenarios in which communities’ profit from conservation, referring to the Amazonian people who stopped cutting down their forests and instead focussed on ecotourism and the US$20 million the Seychelles got to lock up 30 per cent of their ocean.

Hay talked about the “standoff” currently occurring in Cook Islands society, between people who support deep-sea mining and people who don’t. The solution, he said, “can’t be something that is based on facts alone. With scientific evidence, we need to also incorporate values”.

Dr Helen Rosenbaum, who co-founded the advocacy organisation Deep Sea Mining Campaign, focussed her talk on what she called “this dangerous slippery slope that’s just starting toward the industry promoting certain ways of environmental management that would allow them to monitor themselves and regulate themselves”. Specifically, she referred to digital twin technology, which creates a computer-generated picture of the seafloor based on data collected through sensors, and adaptive management, which is an approach to project management that evolves based on new data.

She sees both, which are being promoted by deep-sea mining companies as useful means of monitoring environmental impact, as “inappropriate”.

A member of the audience responded that he works in land-based mining and has seen digital twin technology used successfully; Dr. Rosenbaum countered that the technology isn’t yet capable of simulating the dynamic and complex environment of the ocean.

Dr. Claire Slatter of the Pacific Network on Globalisation said she was there to present an activist’s perspective.

“The planet is in crisis,” she began. “We’ve already reached six of the nine planetary boundaries.” She called deep-sea mining a “foolhardy pursuit”, advocating not for a moratorium – the temporary pause promoted by corporations, governments, and scientists globally – but an outright ban.

Audience member June Baudinet, who described herself as a businesswoman, replied: “I’m not sure I support your view. We’re talking money talk.”

Dr Slatter also expressed suspicion over what she called the international authority’s “permissive rulemaking process” and its “capture” by corporations.

“We need to differentiate between making something legal,” she said, “and doing what is right.”

Dr Teina Rongo concluded Thursday’s symposium with a presentation about what’s changing in the culture and people of the Cook Islands.

“We’re seeing this disconnect not only from our environment but also from being a Māori … I can’t believe we are at this point that we have to teach these things,” he said, referring to basic activities like grating coconuts. In his view and according to his research, “as our economy improves, being Māori declines”.

“We are a communal society but we’re moving more toward individual, and a lot of problems are coming up as a result of that,” he said. He offered his primary concern about deep-sea mining: that more money, as the popular rap song attests, really does mean more problems. For Rongo, the chairperson of an organisation that connects kids to peu Māori, the most tragic modern problem is the loss of culture occurring regionally and worldwide.

“We are all headed in the same direction, but we are at different stages on this path,” he said. “You would think we would look at [places like Hawaiʻi] and learn from them. But we are not doing that.”

The Deep Ocean Symposium ended with Kahoʻohalahala gifting a copy of the Kumulipo, the ancient Hawaiian story beginning in the deep ocean, to whichever Cook Islander could tell him who translated it, and why. The text, he said, is a connective thread to the culture Dr. Rongo referenced, which aligns with and adapts to natural rhythms. “In our Kumulipo, the kuleana (responsibility) given to us as a people is to mālama (care for) our kupuna (ancestors),” he said, “and that means that we have an inherent responsibility to protect everything that precedes us.