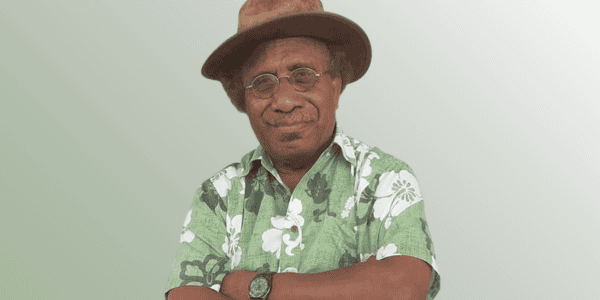

I am honoured to write about John Paska’s passing on 9 August 2024 after a short illness. He was 76 years old. Until recently, he was the President of the Papua New Guinea Trade Union Congress (PNGTUC), an elevation from General Secretary, a position he held for more than 26 years. A fearless advocate for the working class, the organisation and its affiliates might not see someone of Paska’s calibre for a long time. His humility and tactful assertiveness were his trademarks in his long struggle to be a voice for the PNG workers and civil society — a role that was of utmost importance and one that he fulfilled with dedication and impact.

My association with Paska emerged as I began my career as the lone industrial relations lecturer at the University of PNG (UPNG) in the early 1990s. I immediately bonded with the savvy trade unionist during his stint as a protégé under Lawrence Titimur, then PNGTUC General Secretary. This resulted after I returned from Australia with postgraduate qualifications saturated with the peculiarities of its industrial relations system. I was to introduce and mount a diploma program on industrial relations. Initially, it was a hurdle to teach courses laden with the dogma of cooperation and conflict based on Western employment models. It sounded too abstract for the students with PNG traditional backgrounds until one day I invited John Paska to some classes and he fervently turned the course into a captivating spectacle. He was an effective communicator who crafted vivid analogies and linked abstract ideas to everyday experiences of the PNG arbitration system. From then on, the university engaged him whenever he was available.

Trained as a lawyer at UPNG in the late 1970s, Paska’s mastery of advanced industrial advocacy skills is evident by the profound impact he left. He was a fearless advocate and championed the cause of workers, often against powerful adversaries. His voice echoed through tripartite meetings, government corridors and industry gatherings. He was a prominent fixture demanding better wages, safer working conditions, and dignity for those who toiled silently. He wasn’t just a negotiator but a force of nature, unyielding in his pursuit of justice for civil society. Apart from his determination and empathy skills, John Paska had an impressive command of the language. Without an introduction, one would have mistaken him for a distinguished university professor. Hence, the media’s love of Paska and his meticulously crafted press releases and outbursts which paralysed any foe, standing no chance against his relentless determination.

One conspicuous achievement is the gift of the PNGTUC headquarters building and land at the Korobosea suburb of Port Moresby. The donation by the Julius Chan Government in the mid-1990s to the PNG workers and its peak union was cunningly orchestrated to “tame” the firebrand, fellow New Irelander leader. The unification of a formerly loose band of trade union organisations into a coherent entity of the PNGTUC with a single purpose demonstrated his strategic and organisational skills. That achievement brought credibility and respect to his leadership efforts and the trade union fraternity at large. The congress included 25 affiliates, some of the largest are the PNG Teachers Association and the Public Employees Association. The muscular PNGTUC was integral to government policy formulation, board membership makeup, and industry communication.

Paska relentlessly argued that the government should regularly review and adjust the country’s minimum wage to keep pace with inflation and economic conditions. Stubborn governments ignored the call. However, I observed his tenacity to achieve the best for the workers when I represented the PNGTUC on the 2000 National Minimum Wages Board (NMWB). After a 10-year hiatus, the Board increased the weekly wage from a meagre K24 to K60. The massive 40% increase spurred an industry backlash and, with the veto of the government, doomed the application. Subsequent years saw Paska and the PNGTUC succumbing to a K3.50 hourly rate, leaving discretion to the employers. However, the peak union passionately took on the minimum wage issue, drawing attention to the irony in parallels between the country’s resource earnings and its ability to feed its workers.

Paska’s legacy can also be felt internationally, particularly in labour circles. He was a prominent fixture representing PNG at the International Labour Conference, held annually by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva. Sometimes, when he was not travelling, he ensured those who attended were briefed and informed of their task representing PNG. The country’s ratification of 29 ILO Conventions is commendable, and the fact that 21 are in force is attributed to the input the PNGTUC had over the period when representing workers’ rights.

The relationships Paska fostered within the region, particularly with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), remain today. He effectively consolidated the regional network. One outcome was that Bob Hawke (in his trade union leader role before becoming Australia’s prime minister) advocated for the PNGTUC in the 1970s wage tribunals.

Over the past three decades, the full range of trade union rights through to civil liberty issues, including the thorny West Papua question, were commentated on by Paska in the media. However, Paska’s attempts to influence PNG politics directly were futile. His popularity resonated with the population, yet victory evaded him in Port Moresby and New Ireland in the few times he stood for election. That did not stop him and others from establishing the PNG Labour Party in 2001. There was comprehensive support, and even Greg Sword, the then ACTU president, arrived for the launch in Port Moresby. However, the party became dormant with a single-candidate victory in the 2002 election.

Despite his broad appeal, Paska was not immune to criticism. To some of his harshest opponents, he and the PNGTUC were nothing less than loudmouths with little to show for inaction. Sometimes there were outbursts about the peak union’s passivity on a particular issue. To the unsuspecting public, the silence meant the vibrant workers’ voices had been “bought off” by the protagonists. That demonstrated the country’s high expectations of the PNGTUC under Paska, always expecting it to have an opinion on every topical issue.

Yet, unbeknownst to everyone, much less workers, Paska was not backed by a fully-resourced office or the financial prowess of a fully-fledged peak union. In the best of times, an administrative officer kept him company and a security guard kept watch as he sought refuge in the office. Other than that, the PNGTUC was a one-person show in a tiny, dilapidated building. Despite the organisation’s purported industrial muscle, most affiliates existed on paper without financial contribution. Akin to flying a plane on a wing and a prayer, Paska’s management of the PNGTUC demonstrated humility and stoicism. He toiled the first 12 years without wages. He fought for workers to enjoy the fruits of labour rather than himself. Upon his resignation as the General Secretary in 2018, he did not even have a house in Port Moresby. The thoughtful and pragmatic Paska responded, “I do not want sympathy. My only regret is that I had to drag my family into a mission I was dogmatic about. They sacrificed, and I owe them an eternal gratitude debt”.

Paska’s sacrifice for a job he cherished and the workers he loved is a poignant reminder of what it truly means to serve others. In a PNG where many in positions of authority often demand compensation to fulfil their duties, Paska’s humility and stoicism stand out as a powerful lesson. Workers and advocates profoundly feel the loss of John Paska, as his exemplary leadership has left an enduring legacy. His life serves as a beacon of hope for those fighting for workers’ rights and social justice. May his quiet strength and unwavering resilience inspire future generations in PNG.

We extend our deepest sympathy and gratitude to his family for sharing John with us. We know that his sacrifices were made for justice and equality.

Kaim, you fought the good fight, finished the race, and kept the faith. Your work on this earth is done, but your spirit will forever live on in the hearts of those you have touched.

Rest in peace, dear kaim and leader. Your journey may have ended, but your impact will endure!

Kaimio, pupiyae!

Note: In the Enga language, “Kaim” affectionately refers to someone as a brother or close male friend. The final phrase translates as “goodbye, brother!”

Ben Imbun is an academic and development specialist who has taught in PNG and Australian universities. He now works on applied projects in the Pacific.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of this publication.