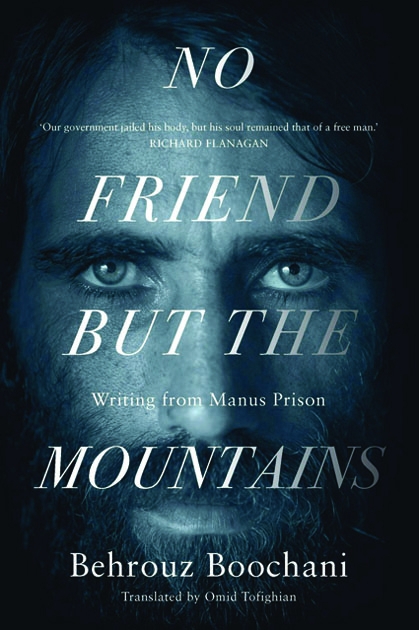

I have resisted reading Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, because as a Papua New Guinean and someone who identifies as being from Manus, I am angry about and tired of the incessant negative portrayals of Manus unleashed by the presence there of the Australian asylum seeker Regional Processing Centre (RPC). I finally picked up the book last November as part of a small project exploring some of the impacts of the RPC on Manus.

The book is a masterpiece. It has been critically acclaimed and widely reviewed, but not from a Papua New Guinean or Manus person’s perspective. Hence this review.

Central to Pacific history, society, politics, culture, and identity is the ocean and oceanic journeys. Epeli Hau’ofa’s famous essay, Our Sea of Islands, highlights the importance of the ocean and calls for every Pacific island to challenge dominant, usually outsider and usually negative, framings of the region. Similarly, for Boochani, the ocean is omnipotent. In the first part of the book, Boochani, an asylum seeker and an outsider to the Pacific, embarks on his perilous crossings across the ocean between Indonesia and Australia. The ocean is the singular harrowing pathway he must follow in search of freedom. It is the judge and the jury, capable of dealing a death sentence. It is the canvas for Australia’s “Pacific Solution”. It is where Christmas Island and Manus Island float, their own agencies apprehended, appropriated as existential parts of what Boochani presents as the oppressive “Kyriarchal System”. In his journey Boochani totally immerses in the ocean and in doing so internalises Oceanic narratives of migration, settlement, and resettlement.

Scholars of the Pacific have extensively discussed the historical and contemporary hegemonic power of Australia, New Zealand and other geopolitical powers in the Pacific. In the second part of the book, Boochani makes these hegemonic transnational powers visible by tracing his transfer within the detention spaces through the borders between Indonesia, Australia and Papua New Guinea.

I was keenly looking out for Boochani’s first impression of Manus. Arriving in Manus, Boochani notes (p. 101):

“Manus Island is in the distance. A beautiful stranger lying in the midst of a massive breadth of water. Where the ocean meets the shore, the water turns white, but further out the ocean wears swampy shades of green and blue. It is a riot of colours, the colour spectrum of madness. Now the ocean is behind us and we are face to face with an exquisite and pristine jungle … Manus is beautiful.”

Sadly, but for very valid reasons because the book centres around the experiences of the asylum seeker, beautiful Manus is quickly subsumed into Boochani’s “Manus Prison”. Boochani’s book is a brutal blow to Manus’s epistemological lens, sovereignty, self-representation, and portrayal.

Throughout the book, the sounds of birds, crickets, frogs, the sea, the jungles, and the “free spirits” of locals, and others, all significant Manus people’s identities and social lives, vividly bring the local context to life. It is sad to see such familiar features of Manus life inscribed into such sorrowful and horrific circumstances even though they all surrounded Boochani during his time on Manus, gifted him their spirits, and formed the fertile ground for his voice to grow. In bringing these beautiful features of Manus to the global arena, Boochani has rendered Manus a tabula rasa and Manus people invisible, inscribing Manus indigenous lore and symbols like a palimpsest to serve his purpose.

In the final part of the book, Boochani explores death as the ultimate outcome of the system; the countless acts of self-harm and the tragic deaths of two detainees. Violence and self-harm became the public face of the centre leading eventually to growing calls by Manus and PNG leaders for it to be closed down. As part of the social impact on Manus Island of the RPC, self-harm and mental health issues that overlay Manus during this period was a public health crisis for the small town of Lorengau, not an isolated issue only affecting asylum seekers and refugees.

Boochani’s book is an important new voice in the Pacific scholarship and literary arena but I admit that I found it unsettling. Boochani and his collaborators speak to an audience where the discourse about asylum seekers is polarised, divisive, and at the heart of Australia’s domestic political sphere. The voter who ultimately defines the system and the reader who sees truth in the book are both predominantly Australians; two wings of the same bird that is the Australian society and its political system. From a Manus perspective, it could be argued that both the detainees and officials are powerful, better resourced, and connected foreign men. If the officials of the detention centre represented the post-colonial powers of Australia over Manus people, then Boochani’s book demonstrates how Manus people are invisible and voiceless in the eyes of detainees.

The book also forced me to think deeply about our complicity, as the people of Manus, Papua New Guinea, and the Pacific in the detention of asylum seekers. Since the 2012 Gillard acceptance of the expert panel’s recommendations to reopen the Manus RPC, the subsequent 2013 Rudd announcement that boat people will never be resettled in Australia, and the ensuing problems in the following years, there has been mainly silence on it and on its broader social impact among Pacific and PNG leaders, human rights advocates, scholars and social and gender experts on the Pacific. Perhaps, and as my review suggests, there is an ambivalence towards what Boochani represents: the oppressed asylum seeker, or yet another powerful encroachment by the world on the region? Moreover, Boochani’s voice, amplified by his international collaborators, only adds salt to the wounds of our own colonial and contemporary experiences of disempowerment and of the dispossession of our own stories that we try so hard to resist.

The world seems to have moved on from the Manus RPC and its “violent hellhole” banner. By mid-2019, with growing calls by Manus leaders to remove the men, they were all relocated out of Manus. Around the same time, the Lombrum naval base project was launched, setting in motion another chapter in Manus encounters with the world. This makes Boochani’s book all the more important. It is a manifesto of the horrors that have occurred in our region, under our watch, and that can occur again if we remain silent. It is an uncomfortable manifestation of changing Oceanic narratives. If you are interested in or teach about the Pacific, don’t resist this book. Read it and reflect on what it means for Oceania, for Papua New Guinea, and for Manus people.

This article first appeared on the DevPolicy blog devpolicy.org from the Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University.

One Comment “Tides that bind: Australia and Pacific leadership”

Comments are closed.