An anti-mining group in Papua New Guinea is calling on its government to explore opportunities in precious metals recycling instead of courting armageddon by allowing seabed mining to happen.

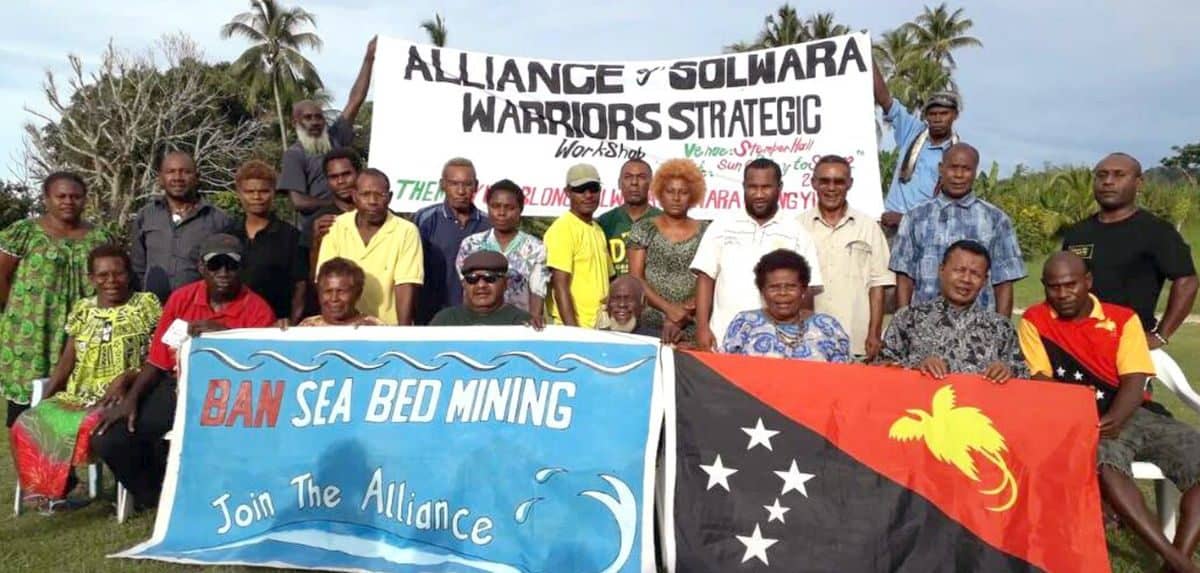

“We are calling for a total ban,” says Jonathan Mesulam, co-founder and spokesperson for the Alliance of Solwara Warriors, a powerful grassroots movement across Papua New Guinea that has relentlessly campaigned against experimental deep sea mining.

“Why not do something innovative, like recycling the metals that we have, instead of digging up our oceans? The seafloor should be the last option. If you want to finish humanity, then go down to the seafloor.”

His comments come as PNG’s anti-mining movement are keeping a close watch on what could possibly be a revival of the defunct Solwara mining projects started by the now bankrupt Canadian mining company Nautilus Minerals Ltd in 2011.

In March, PNG’s Mining Minister Sir Ano Palo confirmed the Government’s intention to pursue discussions with Deep Sea Mining Finance Ltd, which had bought Nautilus Minerals assets including exploration rights to 19 prospective SMS systems in PNG and 25 systems in Tonga.

“All our respective networks are doing their part in advocating in their respective provinces, in Manus, Bougainville, East New Britain, Milne Bay, etc. So we are trying to keep the momentum of seabed mining protests on the ground and also media campaigns and lobbying to continue,” said Mesulam.

“When you have climate change and global warming already threatening Pacific communities, especially coastal dwellers and those who live in low lying atoll islands, the issue of seabed mining becomes just another headache. If a low lying island is impacted by climate change and people are suffering from food security issues, seabed mining comes along and there is oil spill or any form of pollution that endanger the sea and cause irreversible damage, it is a large scale disaster to us coastal communities because we rely a lot on the sea for our food source. We are not guinea pigs to be trialed in this concept. So I think it’s time we are realistic with our issues. Why are we allowing other countries to come into our region and push their agenda? So we are calling on the Pacific partners campaigning against seabed mining that in solidarity, we must put a stop to this nonsense.”

Pacific potentials

PNG is not the only country with minerals in its seabed.

PICs across the region are known to host untold potentials, according to a 2017 World Bank report that profiled them, and this has been the magnet for international mining companies interested in prospecting in their territorial waters.

Cobalt-manganese crusts, rich in cobalt, manganese and other rare metals, have been found in Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Niue, Palau, Samoa, and Tuvalu waters.

Manganese nodules have been discovered near the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Niue, and Tuvalu, and mineral-rich sulphide deposits are associated with hydrothermal vents near Fiji, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, and Vanuatu.

PICs are also active players in advances to mine international waters, which fall under the administration of the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

Already, a number of them have formed partnerships by sponsoring international mining companies to carry out exploration and mining work in international waters reserved for deep sea mining.

Cook Islands, Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati have taken advantage of the provisions in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to sponsor exploration activities in the reserved areas and each has such a company prospecting on its behalf in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a pocket of international waters bordering the territorial waters of Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga and whose calculated resources is around 21 billion tonnes of polymetallic nodules rich in manganese, iron, nickel, copper, titanium and cobalt.

Cook Islands has taken its interest in seabed mining a step further by opening up its territorial waters to minerals exploration work.

Resistance

The interests by governments however are not often consistent with grassroots sentiments, as reflected in the growing chorus of concerns over the impact that seabed mining would have on the ocean, an important source of livelihood for most Pacific communities that live semi-subsistence lifestyles heavily reliant on the sea.

The Suva-based Pacific Network on Globalisation (PANG) highlighted the need for pause due to the lack of scientific knowledge about ocean life in the deep.

“PANG and civil society is under the collective of the Pacific Blue Line. We call for a global ban on deep sea mining on the basis that there is growing scientific evidence now that tells us that the disturbance of ecosystems down there would impact the marine ecosystems and livelihood. We need more time, that’s what science is telling us, we need more time to really understand what’s at the bottom of the ocean rather than rushing to extract minerals,” said PANG’s Deputy Coordinator Joey Tau.

“There is growing scientific evidence that these activities will impact the health of our ocean. We are already in the context of climate change, it’s more likely that it will impact our oceans and will exacerbate the current climate crisis the world is currently headed towards.

If you were to weigh things, there is more calling in terms of the need to have precaution before we rush and that’s why we have been calling on Pacific islands states to take precaution, not to dive into this. To ensure that there is wider consultation doesn’t just mean it’s done at the government level, it needs to be done extensively. What the social and economic impacts are.

We have precedent cases, we don’t have to look far to Africa, the extractives have taught us so much in terms of people displacements, in terms of social crises, you can look at Bouganville, you can look at Banabas, you can look at Nauru in terms of phosphate, you can look at OK Tedi.

So, there’s a lot that you can draw back on. And to those that are already progressing, we need to remind them that there is this need to pause and to really understand the science and carry out consultation. And when we say consultation, we mean ensuring that people are not just fed one side of the information but also share the pros and cons of such experimental projects,” said Tau.

Unknown science

Much of what’s going on in the depth of the proposed exploration and mining locations – which range from 800 metres to 6,500 metres below sea level – remain unknown and unstudied by science.

So far, science has been able to establish that there are typically three main ways minerals are deposited on the ocean floor – through cobalt rich crusts, seafloor massive sulphides (SMS) deposits on hydrothermal vents and ball-shaped polymetallic nodules.

Science is still in the dark however on how life in these locations operate, much less the role they play in ocean biodiversity.

“At hot vents (active vents), the animals are mostly unique to the habitat due to extreme conditions,” said Professor Verena Tunnicliffe, Professor Emerita, Biology and School of Earth and Ocean Sciences at Canada’s University of Victoria, British Columbia.

“The majority are worms, crustaceans like crabs and barnacles, snails and clams, but often quite distantly related to similar animals in shallow waters. Some of the worms and clams/mussels grow to record sizes because they have symbiotic bacteria inside that make their food. Vent communities are of great interest to science and medicine because (a) we have learned about new metabolic processes from the chemosynthetic microbes, (b) the microbial discoveries shed new light on the origin of Life and possibilities of life elsewhere in the solar system, (c) animal adaptations allow us to understand how tissues cope with extreme conditions, and (d) studies have led to development of new genetic technique (DNA sequencing) and to some novel medical compounds.”

Since 2002, Professor Tunnicliffe has held the position of Canada Research Chair in Deep Ocean Research and her research on hydrothermal systems not only led to the discovery of 80 new species of marine life, it also helped establish Canada’s first Endeavor Hot Vents Marine Protected Area.

She has also worked on hydrothermal vents in Tongan and Vanuatu waters.

“We know much less about manganese nodules due to lack of research. The life is much more sparse because the food input is so low. But the sheer extent of the proposed mining will remove substantial habitat. Animals here are highly diverse – most unknown to science. However, most are small with adaptation to the low food and association with nodules. A key issue is the stability of the ecosystem, undisturbed for millions of years, thus nodule growth. We can’t even describe the system, let alone communicate how it may be important to humankind,” she said.

What should be of concern to Pacific communities though is that their ocean is home to most of these newly discovered species.

“There are 153 vent species known from New Zealand, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu and PNG waters. Of these, 90% are only in the SW Pacific and most are only known from one or two countries. These animals are endemic to your vents,” Professor Tunnicliffe said. All the more reason not to rush.