Many Pacific island states are really large ocean states, with vast Exclusive Economic Zones. As local enterprises and overseas corporations seek to exploit the region’s vast ocean resources – from fisheries to deep sea minerals and marine biodiversity – it’s vital to clarify which areas come under the national jurisdiction of which state.

This week, as Fiji hosts the 51st Pacific Islands Forum, there are a series of side events to focus on the oceans and “the Blue Pacific Continent.”

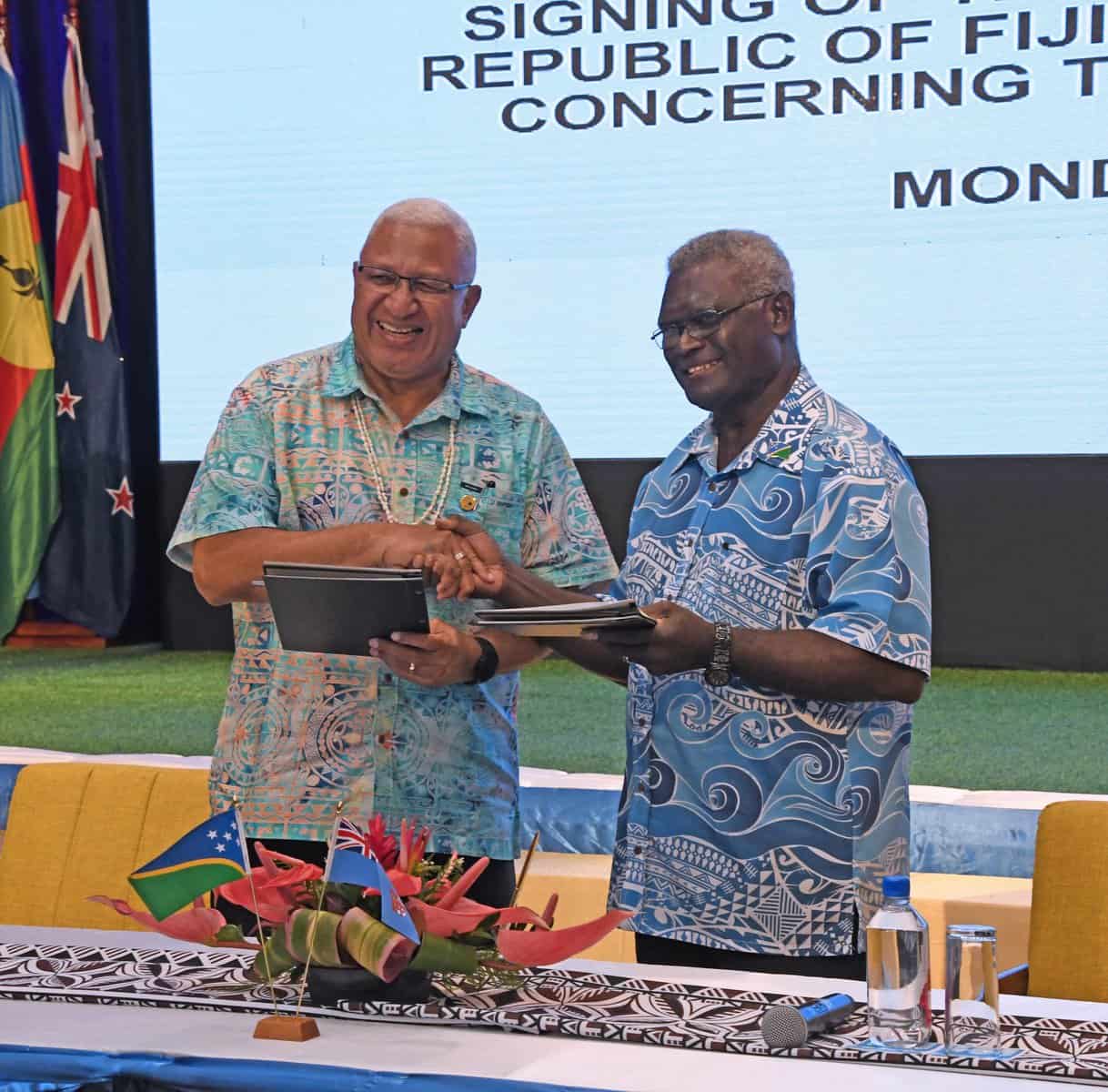

On Monday, Fiji Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama and Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare signed an historic Maritime Boundaries Delimitation Agreement, to demarcate their shared maritime boundaries.

Forum host Bainimarama stated: “The Agreement establishes our countries’ respective maritime zones in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and today marks a promising step towards a brighter and bluer future for Fiji and the Solomon Islands.”

Another agreement this week came as two Smaller Island States formalised diplomatic relations between the two nations. On Monday, Tuvalu Foreign Minister Simon Kofe and Niue Premier Dalton Tagelagi issued a joint communique recognising “the permanency of our statehood and claims to our EEZ, regardless of the impacts of climate change.”

Law of the sea

Pacific island states are seeking to finalise the 45 inter-state ocean boundaries across the region, in line with UNCLOS provisions. Beyond this, they are active in global negotiations for a new global treaty to protect biodiversity in the high seas beyond national jurisdictions (BBNJ), and to prepare for the impact of sea-level rise on low-lying atolls and outlying reefs.

The centrepiece of this week’s summit is the adoption of a “2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent”, highlighting the centrality of the vast Moana for culture, identity, travel and economy. But the Pacific and its ocean resources face many threats – including the multi-faceted impacts of climate change, sea-level rise and ocean warming.

At their virtual meeting in August 2021, Forum leaders adopted the “Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the face of Climate change-related Sea-level rise.” Recognising the future submergence of low-lying atolls and reefs will affect state sovereignty and maritime boundaries, the Declaration states that “once having…established and notified our maritime zones to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, we intend to maintain these zones without reduction, notwithstanding climate change-related sea-level rise.”

Last Friday, the Forum Foreign Ministers Meeting (FEMM) communique also “strongly reaffirmed the regional priority of securing maritime zones against the threats of sea -level rise, which is the defining issue underpinning the full realisation of the Blue Pacific Continent.”

Oceanic diplomacy

Last Friday’s Forum foreign minister meeting in Suva recognised “the importance of Pacific culture, heritage and traditional knowledge in being the basis upon which key regional frameworks such as the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent are based.”

At a time of state-to-state negotiation of maritime boundaries in the Pacific, there are examples where governments have drawn on the expertise and knowledge of customary chiefs and elders, who act as guardians of custom.

Ni-Vanuatu scholar Anna Naupa has argued that the role of culture in maritime zone preservation is often overlooked and needs greater prominence in regional diplomacy. She argues this cultural knowledge and history is vital to overcome “the legacy of a randomly drawn line on colonial maps.”

Just as Solomon Islands has finalised its boundary with Fiji this week, it has also looked south-east to neighbouring Vanuatu. In October 2016, the two countries signed the Mota Lava Treaty, a historic maritime boundary agreement, after more than three decades of inter-state negotiations.

Colonial complications

The settlement of boundary disputes is complicated by the presence of colonial powers in the islands region – United States, France, United Kingdom and New Zealand – that negotiate on behalf of their dependencies.

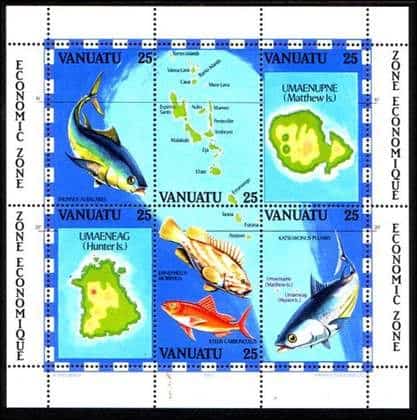

One example is the long-running dispute between France and Vanuatu over two uninhabited islands – Matthew (Umaenupne) and Hunter (Umaeneag) – which highlights the complexity of this diplomacy. Both are disputed territory, claimed by Vanuatu and also France, the administering colonial power in neighbouring New Caledonia.

Even before Vanuatu’s independence in 1980, locals regarded the islands as part of the New Hebrides. In the late 1970s, as the winds of change blew through the region, France claimed the islands – but as part of its neighbouring territory of New Caledonia. Today, legislation in both Vanuatu and New Caledonia claims the two islands as part of their territory.

For France, with its far-flung colonial empire, UNCLOS provides significant economic and strategic advantages. In Europe, hemmed in by other EU member states, France has only 340,290 square kilometres of EEZ. However its overseas collectivities and dependencies add another 11 million square kilometres worldwide (without its territories in the Pacific, Caribbean, Indian and Atlantic Oceans, France’s EEZ would rank 45th in the world).

For this reason, over the last decade, successive French Presidents have paid more attention to oceans policy, extending military, environmental and maritime research programs across the oceans – last year, President Macron announced a billion euros of funding for oceans research, as part of the France 2020 strategy.

However the Kanak independence movement Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) in New Caledonia has taken Vanuatu’s side in the Matthew and Hunter boundary dispute, recognising that customary leaders from the southern islands of Vanuatu have long-standing cultural claims over the two islands.

In July 2009, delegations from the Government of Vanuatu and New Caledonia’s FLNKS met on the island of Tanna, in Vanuatu’s Tafea Province. Together with customary leaders, they signed the Keamu Accord, described as “a solemn commitment between the Kanak people and the people of Vanuatu, that whatever the political and institutional future of New Caledonia, Matthew and Hunter Islands will always remain the property of the people of Vanuatu.”

Paris was not amused and continues to oppose Vanuatu’s longstanding claim. In February 2018, delegations from France and Vanuatu met in Sydney for the first round of talks to resolve the outstanding dispute. A second round of negotiations took place in Brussels, Belgium, in June 2019. Further talks scheduled in 2020-21 were delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The resolution of such disputes over maritime boundaries is important for the regional “Blue Pacific” agenda promoted by the Pacific Islands Forum. There are significant economic and strategic implications for Pacific countries and territories, as they seek to sustainably manage tuna fisheries, other marine species and deep sea minerals at a time of wider geopolitical contest in the world’s largest ocean.