Across the world, new measures are being introduced to keep up with the increasingly sophisticated money laundering and terrorism-financing schemes. The compliance burdens of the anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CTF) rules are intended to make it more difficult for criminals to conceal and use their illicit money. However, the unbanked and poor in some of the world’s least developed countries have unwittingly become the collateral damage of the regulatory process. This article explains how tighter AML/CTF rules affect financial inclusion, remittances, and bank entry in the Pacific.

The main channel for cross-border payments is through the correspondent banking relationship, an arrangement under which one bank (correspondent) holds deposits on behalf of a respondent bank in another jurisdiction, providing payments and other financial services. In layman’s terms, correspondent banking connects a country’s economy with the global financial system by facilitating cross-border payments and currency exchange for trade, investment, and remittance purposes.

As the global AML/CTF regulatory and enforcement landscape has become more stringent, banks are required to undertake extensive scrutiny of their customers’ account transactions and have a greater understanding of their financial arrangements, through the know your customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD) procedures. Failing to comply with these regulations usually brings hefty financial penalties and reputational damage. In 2020 alone, fines related to AML and KYC non-compliance against financial institutions reached USD10.4 billion worldwide.

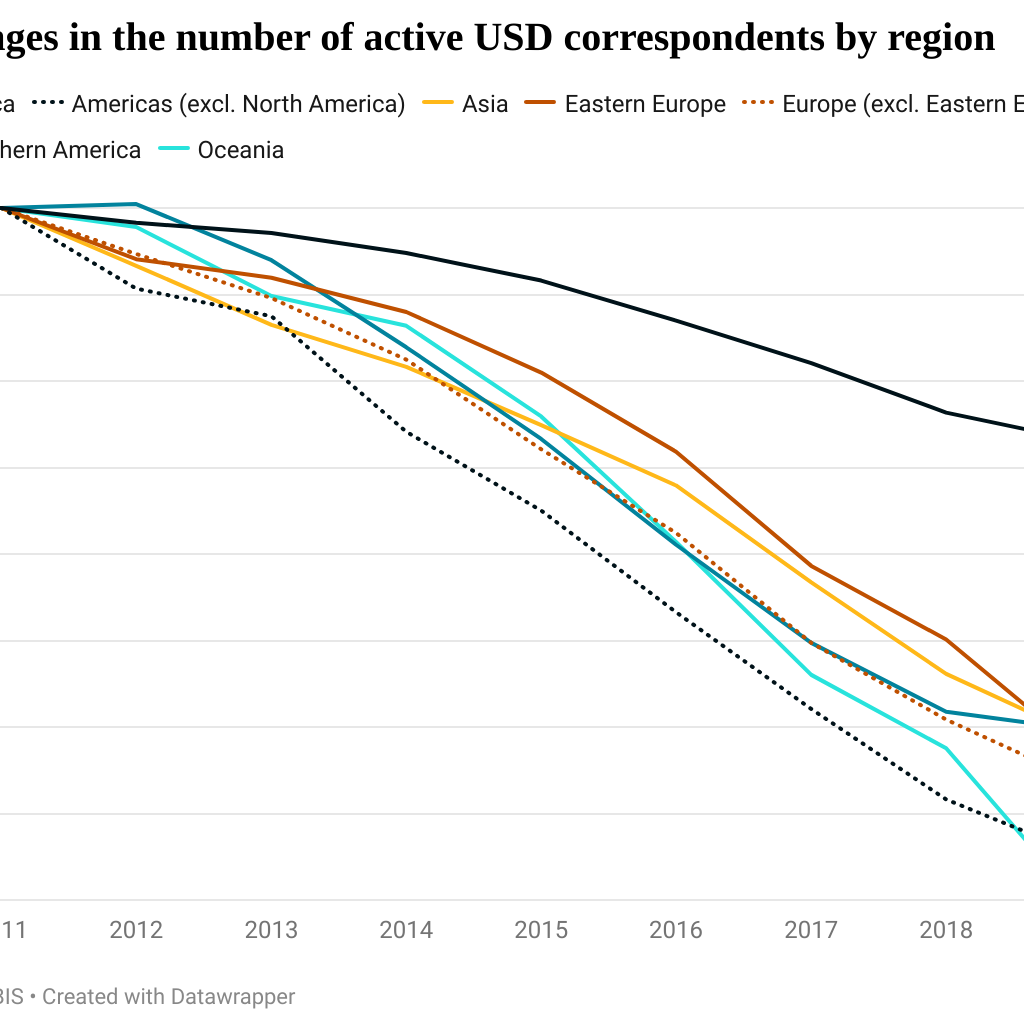

In response, international banks are paying greater attention to their respondents’ AML/CTF program effectiveness and jurisdiction-related obligations. To minimise their exposure to money laundering risks, and reduce the chance of being fined, international banks have started to reduce correspondent relationships with partners they deem risky, a process known as ‘de-risking’. This is leading to a decline in correspondent banking relationships globally, with the Pacific suffering the most, as shown in the graph.

As these relationships become harder to retain, the fear of losing a correspondent banking relationship is apparent; and the steps taken by domestic banks to mitigate such a risk are far-reaching.

First, the process to perform banking transactions has become increasingly stringent. For instance, vanilla farmers in Papua New Guinea (PNG) were not allowed to deposit their harvest income in the bank, because of the lack of documentation such as invoices to prove the source of the funds. The formal sector in the Pacific is not exempted either. There is anecdotal evidence that legitimate cash-intensive businesses have had their bank accounts closed by banks as part of their de-risking strategy.

This is not unexpected. The Bank of South Pacific (BSP), the largest bank in PNG with operations in six other Pacific countries, acted swiftly to hire an additional 40 AML/CTF analysts to strengthen their CDD procedures, after BSP was found to have breached the country’s AML/CTF rules last year.

Another consequence is the disruption to remittance flows. Remittances have always been a feature of Pacific island economies, where they constitute a large part of household cash income, and provide a safety net for many families. Remittances account for 8%, 25% and 42% of Fiji’s, Samoa’s and Tonga’s GDPs respectively.

In the extreme case, a complete loss of correspondent banking relationships, people could lose access to cross-border payments and remittance services entirely. While it is unlikely to come to that, any further withdrawal of the relationship in the region is detrimental, as it could make remittances more costly and increase the use of unregulated channels to transfer money.

In addition, the growing difficulty for financial institutions to establish a new correspondent relationship with an international bank is raising the entry barrier to the banking sector, as a correspondent relationship is a precondition for a banking licence.

In the Pacific, most correspondent services are provided by Australia and New Zealand banks. However, these banks have become very cautious with existing correspondent relationships, and even terminated a few, after they were slapped with record-breaking fines for AML/CTF violations. With a small market size and weak regulatory and enforcement capabilities, many international banks find the risk of operating in the Pacific is not worth taking. For smaller domestic financial institutions, this is making it more difficult to secure a new banking licence.

This article proposes three solutions.

First, CDD procedures should be simplified for activities and sectors that present a low risk in terms of money laundering and terrorism financing. The global AML/CTF watchdog, Financial Action Taskforce, provides some flexibility in the application of its AML/CTF regime, where a country may decide to exempt a specific type of activity from the usual CDD procedures to accommodate financial inclusion.

For instance, in India, small bank accounts with low transaction limits can be opened by individuals with no proof of identity for up to 12 months before official documents are needed to maintain the bank account. This is relevant to the Pacific, where a large part of the population are smallholder rural farmers with little or no immediate access to government-issued identification and income documents.

Second, authorities in the Pacific should actively address their vulnerabilities in meeting AML/CTF compliance expectations. Some progress has been made to improve domestic banks’ KYC reporting capacity and minimise disruption to remittance flows. But more can be done.

One way is through tailoring the regulatory AML/CTF framework and guidelines to the country’s context. An analysis found that the AML/CTF legislation in many developing countries has excessively stringent CDD requirements that exceed the country’s regulatory and enforcement capabilities. A more realistic AML/CTF framework will help domestic financial institutions to better manage compliance expectations and mitigate the risk of losing a correspondent relationship.

Lastly, new technologies and government intervention have the potential to get around AML/CTF barriers. Recent innovations such as digital identity, central bank digital currencies, distributed ledger technology and artificial intelligence have been experimented with in various jurisdictions. Tonga’s central bank has stepped in to offer a remittance service to the Tongan diaspora. If the private sector is withdrawing, governments may need to step in to overcome an induced market failure.

Whatever combination of measures is taken, urgent action is needed. The last thing the Pacific needs is to be disconnected from the global financial system.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University

Dek Sum is an Associate Lecturer at the Development Policy Centre, based at the University of Papua New Guinea, where he is a Visiting Lecturer and Project Coordinator for the ANU-UPNG partnership.

Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are those of the author only.