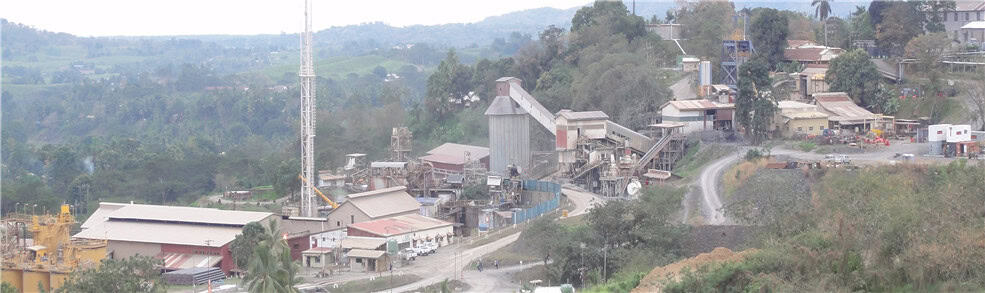

Thirty-three years after it started, Fiji’s longest strike by workers at the Vatukoula Gold Mines came to an end in June, with the Coalition government promising a payout of FJ$9.2 million (US$4.6 million) for the workers as settlement with the Fiji Mine Workers Union.

Coming to FJ$25,000 (US$12,500) for each of the 365 workers, the settlement is too late for 68 others who died during the strike, which protested working conditions. Their grievances included hefty pay deductions for the use . . .

Please Subscribe to view full content...