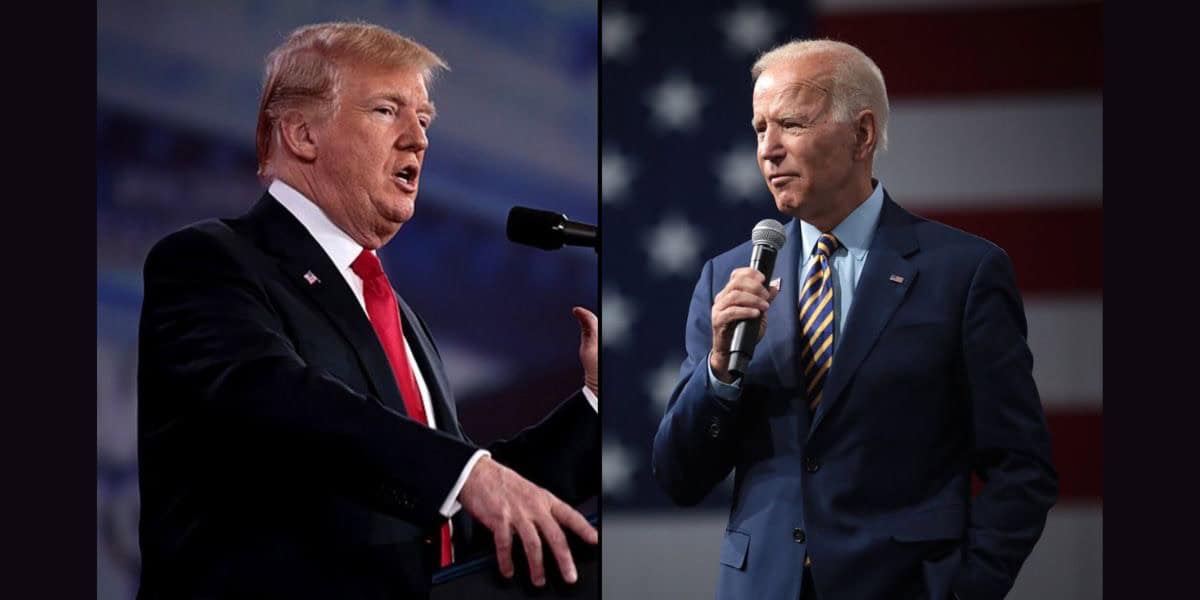

Republican candidate Donald Trump is the favourite to win the US presidential election on 5 November over Democratic incumbent Joe Biden, according to recent forecasts by media outlets such as The Economist. The party conventions, presidential debates and other (less predictable) events over the coming weeks and months will sharpen the focus on the Trump-Biden electoral contest and the two candidates’ very different visions for the country. While foreign aid and global development will not feature in the contest, the topic is receiving some rare pre-election attention.

On the Democratic side, White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has laid out some of what a second term agenda might look like under Biden. Opening a meeting of the US Global Leadership Coalition (USGLC) on 3 June, Sullivan argued that the US needed to work with international institutions and with partners to come with a “better value proposition” for developing countries in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia “on the clean energy transition, on technology, on fighting corruption, [and] on basic development”. While acknowledging competition with China as a key policy driver, Sullivan also argued for the need to improve long-term resilience to prevent crises “from the point of view of displacement, of hunger, [and] of disease”. Interestingly, Sullivan nominated “crushing debt” as a particular area of focus, arguing that the US needed an “all hands-on-deck strategy…[to] help set the stage for more sustainable development as we go forward”.

Asked about specific priorities for a second Biden term, Sullivan nominated “a major initiative with the Congress aimed at truly delivering on the promise of unlocking resources for the developing world”. This would involve “actually resourcing” multilateral development bank reform and debt relief, as well as financing national and transnational “development corridors” based a “more dynamic theory of how you generate development, economic growth [and] stability”. Sullivan argued that this approach “doesn’t require new ideas, it doesn’t require [a] major political shift, it requires resources and prioritisation…”.

Many of Sullivan’s remarks reinforced the Biden administration’s broader development approach, as set out in documents such as its 2022 National Security Strategy. This strategy adopts a “dual-track” approach: responding to geopolitical competition from countries such as China and Russia, while attempting to address longer-term development issues and investing in global public goods like public health and climate change mitigation. It also reflects a more progressive and visible aid presence in foreign policy under the leadership of USAID Administrator Samantha Power.

On the budget front, US aid levels have increased substantially under Biden, although much of the growth has come in the form of successive supplemental spending measures to address crises such as COVID-19, Ukraine and Gaza. As recent analysis by the USGLC shows, the Biden administration’s financial year 2025 budget request to Congress either keeps flat or reduces discretionary spending in areas like global health, non-supplemental humanitarian funding, peacekeeping and long-term economic, democracy and development assistance. And House Republicans have responded by proposing deep cuts to multilateral and humanitarian aid. Nevertheless, under Biden, US foreign aid as a proportion of gross national income (0.24% in 2023; US$66 billion) is at its highest level since the mid-1980s.

On the Republican side, commentary has centred on the policy manifesto developed by the Heritage Foundation and other US think tanks associated with “Project 2025”. This work is aimed at providing a blueprint for an incoming Trump administration to realise its goal of “deconstructing the Administrative State”. In its chapter on aid, the manifesto calls for budget cuts and a rejection of some of the foundational settings of contemporary development policy and programming, including gender equality, advancing sexual and reproductive health, addressing climate change, and other programs associated with what it calls “a self-serving and politicized aid-industrial complex of United Nations agencies, international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and for-profit contractors”.

On gender, the manifesto argues that USAID has been too focused on “adding protections for and ideological advocacy on behalf of progressive special interest groups” and recommends that an incoming Trump administration “should remove all references, examples, definitions, photos, and language on USAID websites, in agency publications and policies, and in all agency contracts and grants that include the following terms: “gender,” “gender equality,” “gender equity,” “gender diverse individuals,” “gender aware,” “gender sensitive,” etc.”

Predictably, it argues the same in relation to all references to “reproductive rights” or “reproductive health” and recommends that a reinstated “pro-life executive order should apply to foreign NGOs, including subgrantees and subcontractors, and remove exemptions for US-based NGOs, public international organizations, and bilateral government-to-government agreements.”

Climate change also appears to be cancelled — “the next conservative Administration should rescind all climate policies from its foreign aid programs; shut down the agency’s policies, programs, and directives designed to advance the Paris Climate Agreement; and narrowly limit funding to traditional climate mitigation efforts”.

In place of these “woke” and “radical” policies, the manifesto argues that a Trump administration should pursue programs that would end the need for foreign aid through a “Journey to Self-Reliance strategy of helping countries exit from aid”. This would include a version of localisation that “ramp[s] down its [USAID] partnerships with wasteful, costly, and politicized UN agencies, international NGOs, and Beltway contractors” in favour of local NGOs, particularly faith-based groups, and “global partnerships with the private sector – corporations, investors, diasporas, and private philanthropies…”.

As with the Biden administration, countering China’s development forays is a key objective. But the manifesto proposes an even more hawkish approach — “[USAID] should finance programs designed to counter specific Chinese efforts in strategically important countries and eliminate funding to any partner that engages with Chinese entities directly or indirectly.” (Emphasis added.) It also calls for greater cooperation on development between the US and “pro-free market” Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India, as well as Taiwan.

Interestingly, the Heritage Foundation document does not recommend that the US follow the lead of the UK, Australia and Canada and abolish USAID (although some Trumpian Republicans are pursuing this in the Congress). But it does call for many more political appointees within USAID as part of a larger agenda of ensuring a civil service that is loyal to Trump above all else. And, ultimately, it is still a very dark and depressing vision of where aid could go under Trump.

One bright spot is that nothing about Trump is predictable. He is unlikely to even read the manifesto, let alone get around to implementing it. Given it holds the purse strings, the make-up of the next Congress will also be a key factor — regardless of the result of the presidential contest. Congress resisted many of Trump’s more extreme proposals to cut aid during his last term and actually increased it when COVID-19 hit.

But, as shown during his last term, there are many areas of policy where Trump would not need legislative approval. And even if only part of Project 2025’s vision for aid were to be implemented, it is not clear that Australia’s current development policy and budget settings would withstand a second Trump presidency. As in defence and diplomacy, we need to be working with others on a Plan B.

Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of the Gates Foundation. The views are those of the authors only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy

Centre at The Australian National University.

Cameron Hill is Senior Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. He has previously worked with DFAT, the Parliamentary Library and ACFID.