A marine scientist who studies a common fishing device’s impact on the world’s oceans – and how to minimise that impact – and a fisheries policy expert urge immediate action to adopt proven innovations.

By Gala Moreno, Ph.D. and Claire van der Geest

About 60 per cent of the world’s canned tuna comes from the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. That means that the treaty-based organisation in charge of managing the world’s largest tuna fishery, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), has considerable responsibility when it comes to the sustainable harvesting of this living natural resource.

It is by no means an easy job to ensure that a highly migratory species like tuna is managed responsibly and with minimal ecosystem impact in the largest ocean region in the world. For the most part, WCPFC has been up to the task.

But the Commission has yet to adopt an innovative solution that research shows will significantly reduce the unwanted mortality of non-target species like sharks. One policy change—the adoption of a measure to require the use of what are termed “non-entangling fish aggregating device (FADs)”—could do just that. And, even better, such non-entangling designs do not adversely impact the success of fishing operations that rely on FADs to aggregate tunas.

The WCPFC has been a leader in tuna conservation for many years—from adopting 100% observer coverage for purse-seine vessels and a unique regional observer programme, to establishing a centralised vessel monitoring system (VMS). Its member states lead, too, such as the Pacific Islands Forum Fishing Agency (FFA) and Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) members, who have put in place innovative measures in their waters to control fishing effort, collect data, and manage FADs.

Now it is time for the WCPFC and its members to take a further step. WCPFC must follow the lead of three other Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) and adopt a measure at its annual meeting in December 2017 requiring the use of non-entangling FADs designs.

Understanding a Key Fishing Device

First, it is important to explain what a fish aggregating device, or FAD, is. FADs are floating objects at sea that vessels use to aggregate tuna. Over 40 per cent of the global tuna catch is made with FADs, which are in use by large-scale commercial fleets as well as in artisanal and sport fisheries as a way to improve efficiency.

A shark entangled in the netting of a traditional FAD.

But not all FADs are created equal. Though FAD designs vary greatly around the world, traditional man-made FADs have consisted of rafts and often-extensive underwater structures with netting and other materials. They can be anchored to the ocean floor or drifting. This design has created problems when the mesh size is too wide or when tears in netting create holes large enough to trap sharks and other marine animals.

Working Together to Address FAD Impacts

But there are always answers to these kinds of ecological problems if we look hard enough. That’s why organisations like ISSF have devoted countless hours and resources to understanding and addressing FAD impacts. Through on-and off-the-water experiments and workshops with fishers and scientists, we’ve found many options that are increasingly embraced by the world’s tuna fishing fleets.

There is a spectrum of designs for non-entangling FADs. The main qualifier for a non-entangling FAD versus a traditional FAD is that non-entangling FADs should have small-mesh netting or no netting at all on the raft and in the water beneath the raft. Instead, they should use materials like canvas, rope, bamboo or palm leaves. These FAD characteristics can significantly reduce the entanglement of non-target species like sharks and turtles.

Designs are constantly evolving and improving. The most ideal non-entangling FAD is also a biodegradable one, built with materials that are less likely to cause ecological damage. The materials used to build traditional FADs tend to be long-lasting and inorganic: nylon mesh, fishing nets and PVC pipes, which contribute to marine debris, reef damage and ocean pollution when they sink, disperse or wash ashore. Using ropes or cotton canvas instead of netting can reduce entanglement, and biodegradable materials like balsa wood instead of plastic PVC piping can prevent plastic marine pollution.

A summary of recommendations for FAD designs from the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF).

It’s important to note that research on biodegradable FADs is ongoing; this is not a call for WCPFC to adopt their use immediately or as urgently as non-entangling ones. But biodegradable designs are the next-and-near frontier in FAD design innovation—something we are working hard on with a diverse set of stakeholders, including industry, scientists, and fishers. Given their pollution-preventing potential, biodegradable FADs also are supported by the Common Oceans ABNJ Tuna Project, sponsored by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the European Union and others like the International Pole and Line Foundation, with whom ISSF is working on pilot projects. Rest assured, we’ll be calling for the adoption of biodegradable FAD measures, too, at WCFPC and every tuna RFMO in the very near future.

Action on a Widely Accepted Innovation

Our research about the feasibility, effectiveness and the need for widespread adoption of these new designs is extensive and supports the idea that an out-with-the-old, in-with-the-new position should be taken in all fisheries. Based on the research, non-entangling FADs are the best method we have for reducing entanglement or “ghost fishing”. And our research and consultation with numerous fleets and vessel captains around the world indicates that using these designs does not reduce how much tuna is aggregated beneath a FAD.

In fact, a growing number of fleets are already on board with the concept of non-entangling FADs. Skippers Workshops organised all over the world by ISSF have also shown that fishers, ship owners and skippers are not only not resistant to using non-entangling designs—they are already using them.

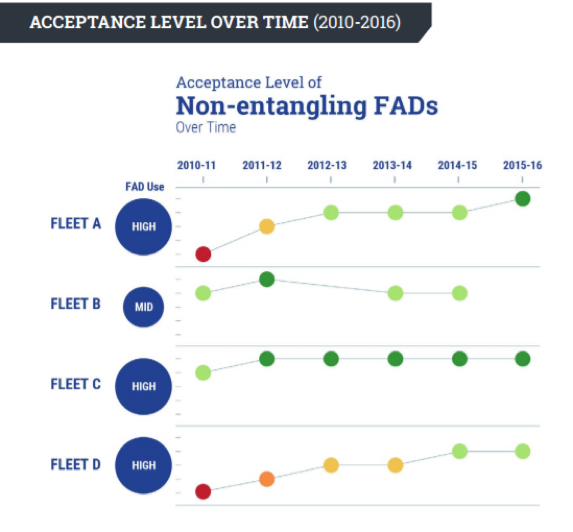

This chart shows the growing acceptance to use of non-entangling FADs among tuna fishing fleets.

This chart shows the growing acceptance to use of non-entangling FADs among tuna fishing fleets.

We talked with fishers in nearly all major tuna purse-seine fleets, and based on their positive or negative comments, recorded an average acceptance level. The response to the use of non-entangling FADs in most recent surveys has been encouraging, to say the least.

The WCPFC is the biggest tuna fisheries management organisation in the world, and requiring the fleets of member nations to transition to non-entangling FAD designs would have far-reaching, positive impacts for the region. The Commission’s meeting this week is a perfect opportunity to do the right thing for the marine life and ecosystems upon which so many industries and coastal communities depend.

###

Dr. Gala Moreno’s research focuses on the effects of fish aggregating devices (FADs) on tuna and their ecosystems, and on discovering ways to reduce FAD impacts. She has worked with purse-seine fishers from the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, absorbing their knowledge of tuna behavior and fishing strategies, for almost 20 years.

Claire van der Geest helps guide ISSF policy engagement in the Pacific and Indian Ocean regions. A marine ecologist and international development practitioner with almost 20 years’ experience, she is focused on fisheries policy and development of best practices, particularly related to minimising the impact of fishing on the marine ecosystem.