IN a recent whirlwind visit to Samoa and Fiji, ADB President, Takehiko Nakao signed several important agreements, including one that scaled up the status of the Samoa office from an extended mission to a country office. He also met dignitaries, held media conferences in both capitals, visited ADB projects outside of Apia and visited Denarau and Natadola along Fiji’s Coral Coast, the sites of the ADB Board of Governors’ 52nd Annual Meeting in the first week of May later this year.

Nakao’s visit came in the aftermath of the various announcements of packages of (mainly infrastructure) funding from Australia. It was thus an excellent reminder to all concerned that when it comes to infrastructure funding and more, ADB has a long-proven record in the Pacific. The bank has been operating for more than half a century and is not likely to be giving up its prominent regional role to any Johnny-come-lately.

Nakao’s visit was strategic in its timing. Strategic in that the visit was aimed at consolidating ADB’s long-term position as a regional development bank that has ably proven its existence and services. The visits to Samoa and Fiji achieved their respective aims of re-enforcing the bank’s long-term aim.

The scaling up of the Apia office from an extended mission to a country office is indicative of what ADB is proposing to do with three other extended missions in Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. Such upgrades reflect the volume and complexity of ADB’s lending businesses in those countries. For Samoa in particular, the up-scaling of its office has a symbolic significance: of all the 13 Pacific Island Countries ADB members, Samoa is the only foundation member with effect from 1966.

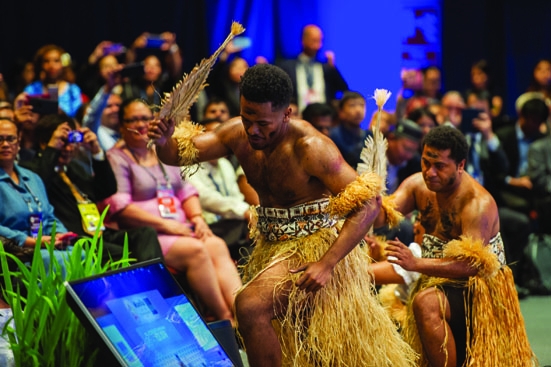

Fiji’s first ever hosting of an ADB Governors’ Annual Meeting in early May this year will be a historical first for Fiji, an ADB member since 1970. But it will also be strategic from ADB’s perspective. It is underpinning ADB’s geostrategic focus for the future to the Pacific Ocean that has been brought to greater prominence by the declaration of an over-arching Indo-Pacific by the Quad members, including Australia. Such prominence is of unprecedented interest in that the Pacific Islands Forum has responded with its Blue Pacific narrative to drive its ‘strategic autonomy’, its geostrategy in the context of a larger political construct that has totally encircled the region and beyond.

Once scaled up, the Samoa country office will bring the total of all country offices in the region to eleven. These will supplement the ADB operations carried out by the resident mission in Papua New Guinea, by the Pacific sub-regional office in Fiji and by the Pacific Liaison and Coordination office in Australia.

The media release for Nakao’s visit gave an insight of what ADB has in prospect for the immediate future. “Across the Pacific region, ADB is significantly scaling up financing to help developing member countries achieve sustainable economic and social development, while strengthening climate and disaster resilience. The volume of ADB active projects in the Pacific has doubled every five years since 2005 and exceeded $3 billion as of the end of 2018. The volume of active ADB’s projects in the Pacific is expected to surpass $4 billion by 2020.”

With that expansionary scenario, expectations of each member country will be consequently heightened and increased engagement with the Bank will ensue. If the ADB-Fiji partnership for immediate financing is any indication, it can be expected that for each member country, the volume and types of financing will increase, and sectorial coverage will widen, including lending to the private sector. Furthermore, all investment requirements for climate change and disaster-resilient infrastructure assets will be an essential element for any country member entitlement.

In such a situation, especially in the context of increased infrastructure funding from other sources, ADB’s strategic approach would, by necessity, tend toward increased concessionality. As it is, ADB is already in that business. It presupposes more. The bank’s Asian Development Fund already offers concessional loans and grants and technical assistance to lower-income developing member countries. Further, it enjoys the capacity to convert concessional loans to grants should economic and financial conditions demand such conversion. Samoa has already benefited from such concession in January 2018 following a series of environmental disasters that struck that country.

The quintessence of Nakao’s visit was what was left unsaid, but it raised serious questions about the coherence of our regional approach in the context of the Indo-Pacific, especially the various funding proposals that have emerged in the name of this imposed political construct.

Australia, one of the architects of Indo-Pacific, joined Japan and USA at the APEC meeting in Port Moresby last November to announce their ‘Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment for the Indo-Pacific.’ Prime Minister Morrison did clarify that financing from this source is essentially loans that are bankable. India, a fellow Quad member, was left out of the Trilateral Partnership.

Not long after that, Prime Minister Morrison announced a further A$3 billion (US$2.12 billion) Pacific Infrastructure Bank, comprising A$2 billion financial facility: Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) – for loans and grants for transport, telecommunications, energy and water projects. The balance of A$1 billion will be disbursed through the Export Finance Corporation (EFIC), to encourage more Australian firms to invest in the Pacific.

This funding is aimed at countering China’s influence in the southwest Pacific, and there’s the rub!

Statements from both Australia and USA are mixed: anti-China sentiments as against those infused with a veil of friendly rivalry, competition, ‘partnership rather than confrontation.’ The inconsistencies are particularly worrisome. On balance, when these statements are viewed against specific actions to counter China, there are reasons for pessimism about the prospects of Indo-Pacific.

Nakao’s interest would have been piqued by the paradoxes relating to Indo-Pacific and how an ADB member country was faring in the cross-fire that has ensued.

China joined the ADB in 1986. It created its own Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in January 2016. Prior to that in 2013, China initiated its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). To date, nine Pacific Islands Forum members have signed onto the BRI. The latest report from the Cook Islands, one of the signatory-PIF members, revealed a statement in a “US intelligence report accusing China of currying favour with Pacific countries through bribery and infrastructure investments.” The Cook Islands Deputy Prime Minister, Mark Brown, reaffirmed the utility of its BRI projects and underscored that these projects were not able to be financed by traditional development partners.

President Nakao is back in Manila. His unsaid message remains loud and clear, the ADB is the region’s top development bank. It can accommodate all our needs, notwithstanding those funds created specifically for climate change activities and for which ADB will mobilis e co-financing. There is no need for more. For the Indo-Pacific, ADB remains relevant. It remains committed to the region and stands ready to work with all its 15 Forum members in the execution of the region’s Blue Pacific narrative that seeks strategic autonomy in the context of a region that is becoming complex and geopolitically-charged.