Papua New Guinea’s media council has condemned as “concerning” and “shameful” the exclusion of a BenarNews journalist from media events during a visit by Indonesia’s President-elect to the capital Port Moresby on Wednesday.

Papua New Guinean reporter Harlyne Joku was excluded from a media briefing with Prabowo Subianto and Prime Minister James Marape, a move that reportedly came at the request of the Indonesian embassy.

The ban on Joku prompted a sharp rebuke from the Media Council of Papua New Guinea, which decried the incident as “an attack on PNG’s independent media sector, and an affront on PNG’s political sovereignty.”

“This is not the first time for visiting foreign delegations to impose restrictions on PNG journalists covering their events,” said council president Neville Choi.

“It is also not the first time that PNG government officials have acquiesced to such requests against coverage of events made accessible to all accredited PNG media.”

The incident comes amid growing concern about the government’s plan to regulate the press under its so-called media development policy.

Prabowo was visiting Port Moresby on his way home from Canberra, where he finalised negotiations for an upgraded defence treaty between Australia and Indonesia.

Joku said she was denied entry at Jackson’s International Airport to cover Prabowo’s arrival, despite being accredited to cover the event by the PNG foreign ministry and the Department of Information and Communications.

She was later told by a foreign ministry staff member that she had been removed from the list of approved journalists at the direction of Indonesian officials.

Joku appealed the ban with the office of Foreign Minister Justin Tkatchenko, which intervened to allow her to cover Prabowo’s arrival but not a press briefing with Marape.

While she was later told by an Indonesian government official that it was a case of miscommunication, she was still denied access to the joint leaders’ press conference later that day.

“It’s also shameful that the PNG government officials involved in this international visit allowed this to happen to a PNG journalist,” said Choi.

The foreign ministry declined to comment on the incident and referred questions to Marape’s office and the Indonesian embassy – neither of which replied to BenarNews.

PNG journalists have had to contend with similar efforts to undermine their work before. Local journalists were reportedly told not to ask questions about Indonesia’s Papua region – commonly referred to as West Papua in the Pacific – during a visit by foreign minister Retno Marsudi in 2015. They were also excluded from press conferences during a trip by former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2017.

More recently, PNG journalists were unable to ask questions or were excluded from press briefings during a visit by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in 2022.

Choi said Joku’s ban was even more abhorrent because the restrictions appear to have been made because of her background and recent coverage of the independence movement in West Papua.

Joku, who is based in Port Moresby, was born in Sentani in Indonesia’s Jayapura regency and has recently covered stories concerning human rights abuses in the region and West Papua’s push for independence.

“The atrocities inflicted on the people of West Papua by the Indonesian government are not a taboo subject for the media in PNG,” Choi said.

Thursday’s incident has put a spotlight on what many journalists in PNG say are government attempts to weaken journalistic independence.

Marape has threatened to hold journalists accountable for news reports he objected to and has frequently criticized coverage of his government’s failings and PNG’s social problems.

His government’s plan to regulate the media has been criticized by journalists and civil society groups because it contains avenues for politicians and officials to undermine the watchdog role of the Pacific island country’s media.

The country’s global ranking in the annual Reporters Without Borders press freedom index deteriorated to 91st place this year from 59th last year. In 2019 it was placed 38th out of the 180 nations assessed.

Tkatchenko ahead of Prabowo’s visit told national newspaper the Post Courier there would be a game changing announcement made after the bilateral meeting, but little of substance was revealed after the talks.

The two leaders put on a show of bonhomie while avoiding mention of any contentious issues, such as their relationship over their shared 760-kilometer (472-mile) border.

The border has been a source of some friction between the two countries over the decades, with Indonesia concerned by the prospect of Papuan insurgents moving between both countries.

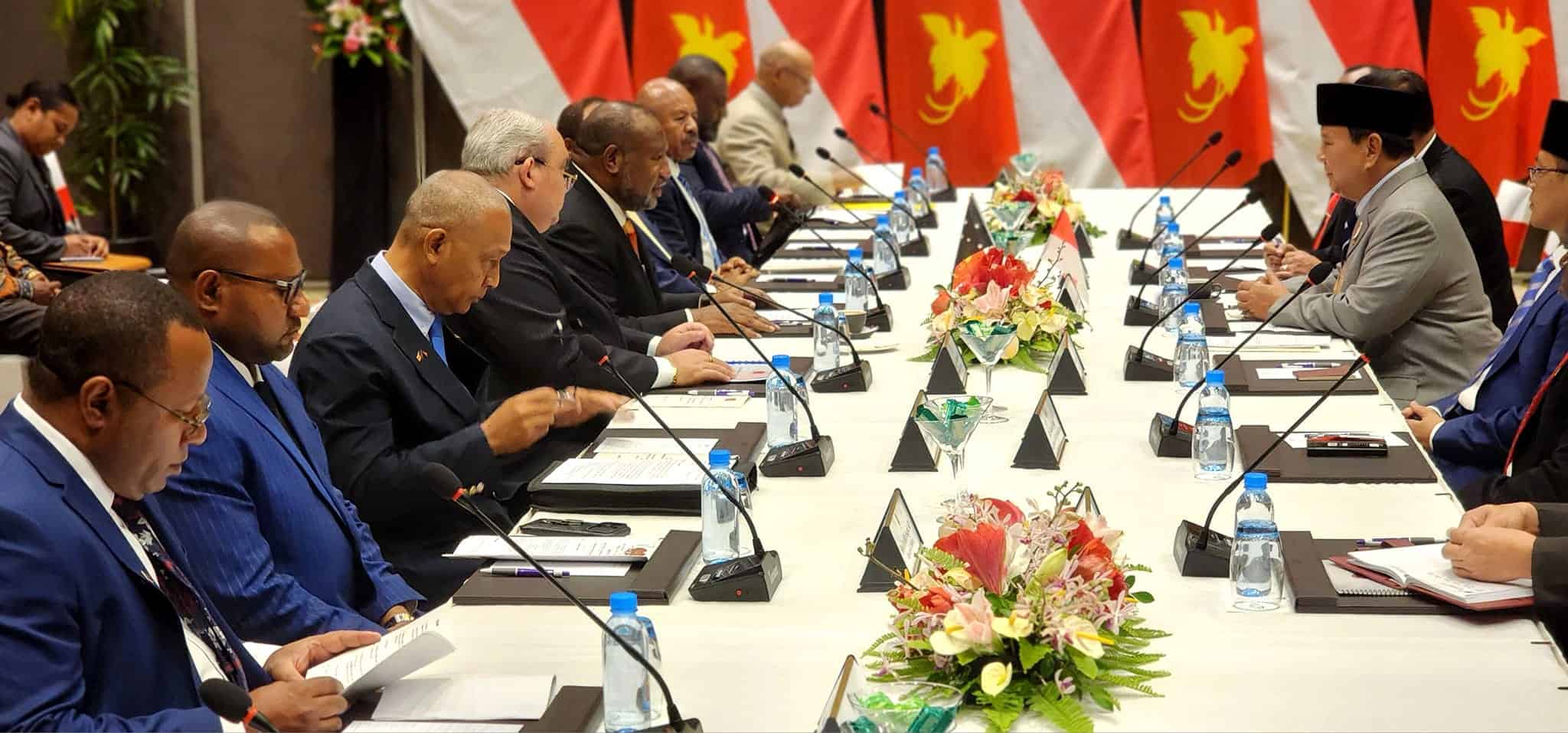

During a press briefing in which journalists were not allowed to ask questions, Prabowo said PNG could provide advice on respecting Melanesian culture and traditions of Papuans on the Indonesian side of the border.

Within Papua New Guinea, there is a grassroots support for the Papuan independence movement in Indonesia, but the government says it recognises Indonesia’s sovereignty over the territory.

Prabowo, who is currently Indonesia’s defence minister, takes office in October after he won by a landslide in the 14 February presidential polls.

His presidency is being met with apprehension by some observers and human rights groups, who are fearful that accountability for past human rights abuses in Indonesia may be pushed off the agenda.

The ex-general, who was married to the daughter of long-time dictator Suharto, was dismissed from the army in 1998 for kidnapping student activists. While with the army’s special forces (Kopassus), Prabowo was linked to alleged atrocities during the invasion of East Timor and military operations to suppress the insurgency in the Papua region. He has previously denied involvement.